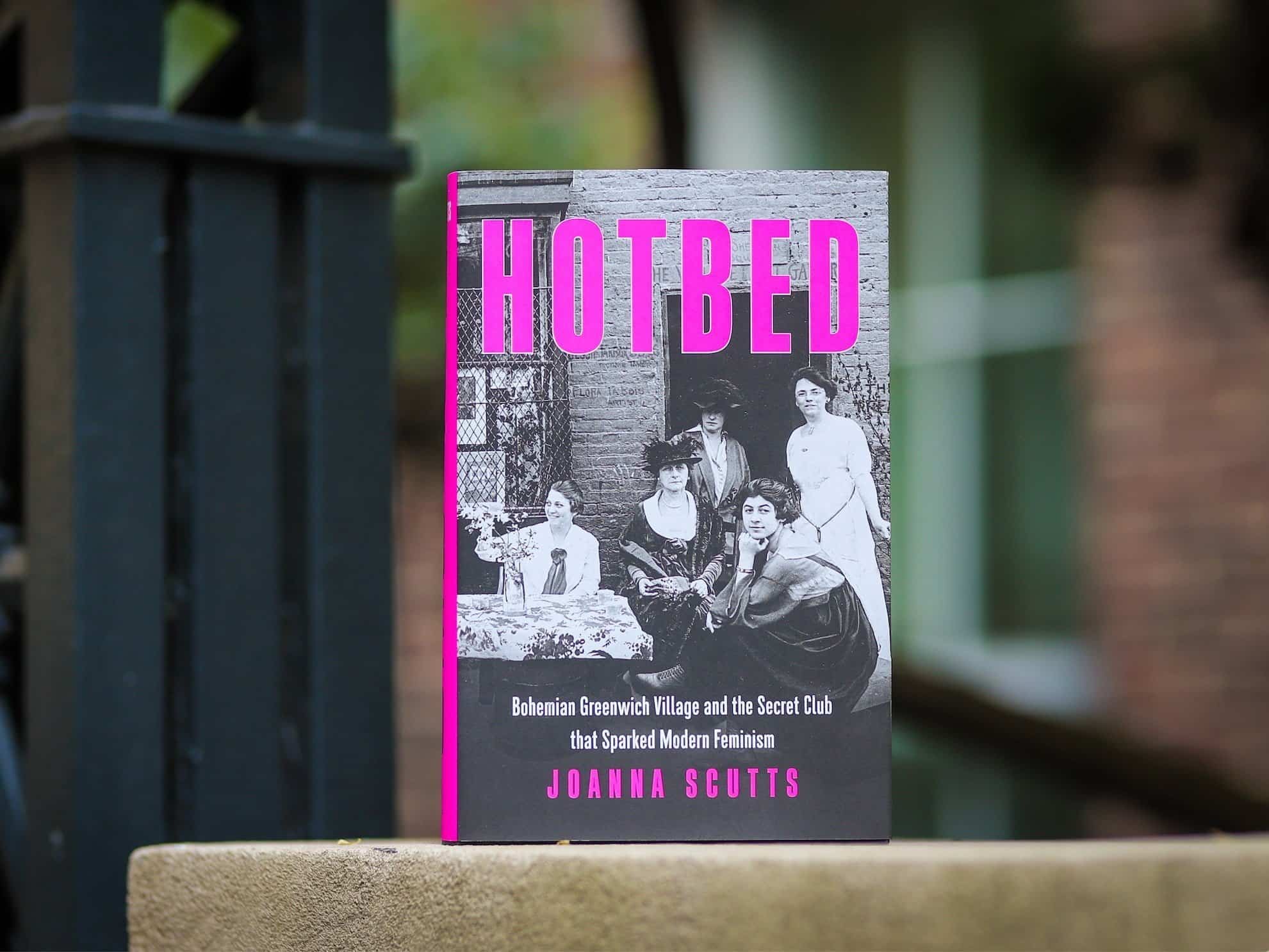

As I was reading Joanna Scutts’ new book Hotbed: Bohemian Greenwich Village and the Secret Club that Sparked Modern Feminism there was breaking news that the settled cases of 50 years, Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey were officially overturned by the Supreme Court of the United States. In one stroke of a pen over half of the country had been relegated to second class status, now with reproductive healthcare and privacy protections no longer constitutionally guaranteed. According to statistics, an estimated one quarter of persons assigned female at birth have had a safe legal abortion since 1973 when Roe was first decided to guarantee a gravid person’s medical freedom and decision to terminate a pregnancy.

It really is true that freedom can be fleeting and that hard-fought victories are not the end of a struggle, but only the beginning of new valuable rights that must be jealously guarded and rigorously protected – otherwise they will be taken away.

As recounted in Hotbed, in 1912 suffragist Marie Jennie Howe, trained as a Unitarian (though not practicing) minister, founded this elite women’s club which began meeting every other Saturday in at Polly’s restaurant on MacDougal Street (and the Liberal club upstairs) in Greenwich Village, NY. The members of this group were college educated public figures in the fields of business, law, medicine, writing, journalism, and the arts. Membership required a keen interest/passion for women’s issues, producing work that was “creative”, and keeping confidential the discussions that occurred during these meetings.

The openness of discussion and entertaining of all unusual viewpoints is what gave this group the idea of calling their club “Heterodoxy.” (Anything outside of the mainstream…with many points of view).

No notes or records of the actual meetings were recorded, keeping the subject of meetings private, secret, and confidential. Thus, all the information about this club and its 25 charter members were gleaned from personal histories and memoirs outside of the actual business of Heterodoxy. These women leaders flourished outside the traditional domestic sphere and were passionate about debate around ideas that upended cultural norms around politics, women’s issues, and sexuality.

Some believed that domestic work and child rearing should be professionalized with high compensation to free up women in other professions outside the home. Professionalizing and paying well traditional domestic and childcare workers also uphold the value and necessity of traditional “women’s work.” Even an effort to create a dream apartment for families with working moms that provided high level and high paying domestic/childcare services was tried, but ultimately abandoned for lack of sustainable resources.

Heterodoxy, active from the 1910s – 1930s, was the most radical of women’s clubs at the time, arguably developing second wave and modern feminist theory, thought, and activism. The club’s mission was to creatively upend social norms to make women’s lives better. Nothing was off the table for discussion, which frequently became passionate and lively. Topics and projects examined included women’s suffrage, Prohibition, anti-war activism, labor rights, sexual freedom, birth control, psychotherapy (Freudian and Jungian), avantgarde art and experimental theater (from which Eugene O’Neill plays became renowned), and promoting socialism and/or anarchism. Political activism, social progressivism, and anti-poverty efforts, protests, parades, fundraisers, and theatrical performances all grew from these club meetings. Humor and satire did keep things moving on the theatrical artistic side.

Not all members agreed with everything. Some embraced specific issues, such as changing the law of the land (or an individual state) to give women the right to vote. Pro-women’s suffrage protests at the White House in 1917 and 1918 resulted in more radical members being jailed at the Occoquan workhouse in Virginia.

Other members thought it more important to pay attention to and uplift anti-lynching campaigns. One interesting note was that Grace Nail Johnson was the only Black woman who was a member; blind spots exist in even well-intentioned spaces.

Firebrand Elizabeth Gurley Flynn pushed for stronger labor laws to protect employees after the tragic Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911 that killed 146 garment workers.

Much of the drive for women’s suffrage lost its steam when members put their energies into peace activism to keep the United States out of World War 1. The resulting failure of this and the Spanish Influenza Epidemic of 1917-1918 probably contributed to delay of passage, but on June 4, 1919, Congress passed the law to have the 19th Amendment to the Constitution sent to the states. And finally on August 18, 1920, it was ratified, granting women the right to vote.

Socially, Heterodoxy welcomed and promoted what were deemed “experimental” lifestyles at the time … namely lesbianism and bi-sexuality, group or polyamorous relationships, and open marriages. Divorce, which was rare at the time due to the expense and the resulting social shunning, was more prevalent amongst heterodoxy members. Only a few members had children, too.

Whatever was happening politically, socially, and personally, many of these women became and remained lifelong friends. Scutts does trace some of these women’s relationships and experiences before, during, and after Heterodoxy’s heyday.

Some of Heterodoxy’s members found different callings with which to place their attention. Some members moved abroad; others moved out west. Some members became tired of others’ enamored focus on Freudian analysis/psychotherapy even to the point that satirical skits were written about it. Active feminism did seem to become dormant in the decades following the 1930’s. Severe global depression and World War 2 did take a toll on feminism, but with one exception. During the American draft, many women were asked to take over factory jobs to support the war effort. Then during peacetime, many middle-class women realized they liked and missed working outside the home and the potential for economic freedom it provided.

After several decades, the roots from which the Women’s movement of the 1960s and 1970s and with the push for the Equal Rights Amendment (which missed being passed), women’s bodily autonomy and economic freedoms (like establishing credit in her own name), and the movement to prevent violence against women became the next goals for women’s social justice in the United States. The idea of demanding institutionally backed personal freedom for women as developed from the meeting of the minds in Heterodoxy earlier in the century was reignited at this time.

Now today, we’re in a period of dissent once again.

Hopefully, this time a critical mass of people is paying attention to the backward slide that is happening and is saying “hell no.” Hopefully, we as women are recommitting ourselves to demanding our rights and dignity as equal citizens to our brothers.

This time we must center the poor and working class and all marginalized voices in this fight, as they are the ones who stand to lose the most. This time we must put in sweat equity no matter how long it takes. Hopefully, enough of our brothers will join us in allyship.

With online interconnectedness we have the ability to reach out to each other as groups of people who want to reclaim, maintain, and enhance women’s rights. The members described in Hotbed prized creativity in problem solving. They had one vision – with all options on the table – to make women’s lives better. Right now, making a priority to make poor women’s, all women’s, lives better is a potentially powerful unifying force. Protests and rallies are great. However, there needs to be a philosophical structure underneath to support that. Checking out recommendations by Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and by the Pennsylvania Coalition Against Rape informs about legislation, empowers patients, and gives options for optaining safe abortions. Being willing to provide finances for poor women who need to travel for their abortions is a solution. Any one of these activist projects to protect women’s healthcare is empowering. As shown in Hotbed, finding your group to protect women will sustain this movement over time. The common bonds and working together creatively give hope and moral courage.

Since this struggle ahead looks like it’s for the long haul, as was the case with the women’s suffrage movement 100 years ago, let’s make this a full vast commitment that’s tempered with good humor to keep us energized.