Today I’m taking a detour in the kind of book I usually review.

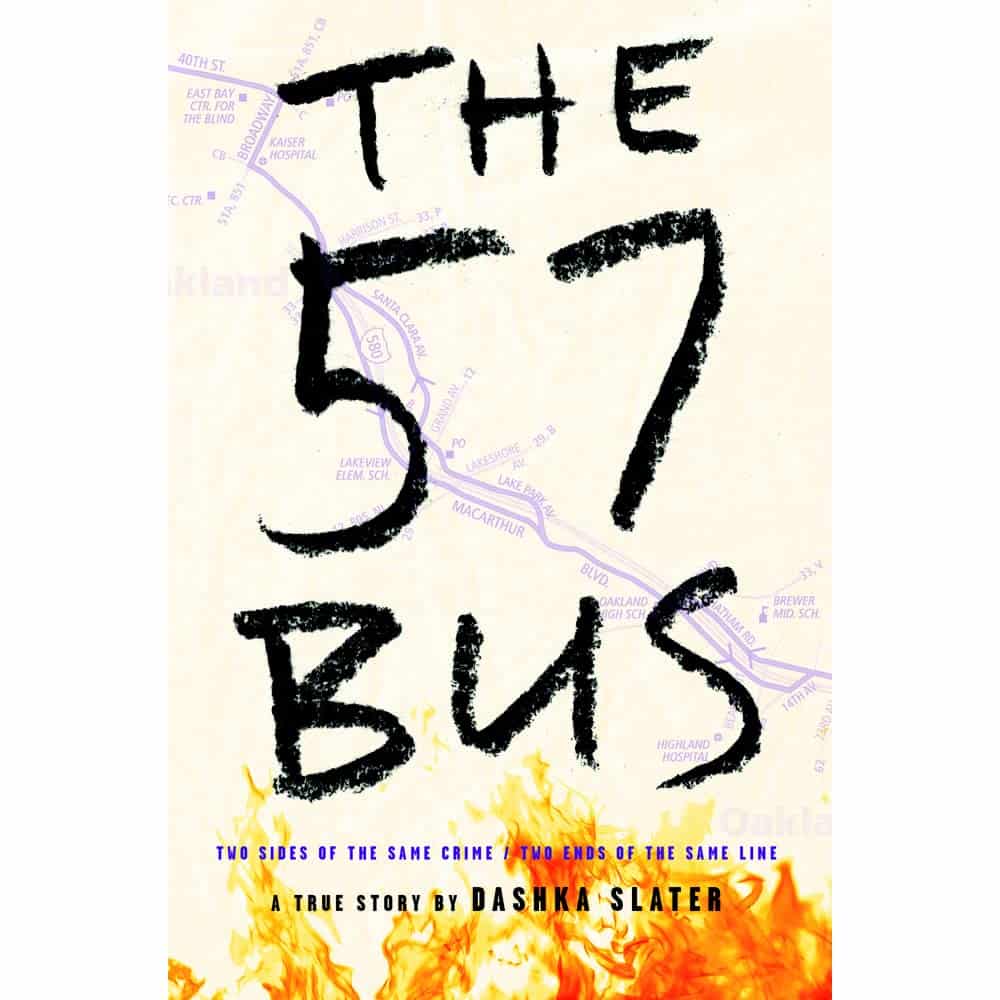

The 57 Bus is a true crime story written specifically with the young adult reader in mind. The author Dashka Slater takes the reader through events leading up to a horrific crime that was committed in Oakland, California, in November 2013.

A Black youth, Richard Thomas (not the actor who portrayed John-Boy Walton on the TV series The Waltons), aged 16, lit 17-year-old Sasha Fleischman’s skirt on fire while that person was dozing on a bus ride home from school. Sasha identifies as agender and neurodivergent. The 57 Bus explores the intersectionality of race, class, gender, gender identity, crime, the criminal justice system, how we view juvenile culpability, and the process of police interviews of young suspects. It asks the question: “What is a hate crime, and how do we figure out intent?”

This book also explores what happens when children and entire communities are deprived of emotional and economic resources basic to the process of healthy decision-making.

Slater researched this crime and the legal aftermath based on interviews with people close to both the victim and the perpetrator, and with the compassion and clarity of someone without an agenda painted a portrait of both young people’s worlds before and immediately after the awful event. She used personal journals and letters by both youths to help the reader get to know both.

I was resistant to reading The 57 Bus in part because I feared being forced to take a side, whether it was to be angry over and for an upper middle class victim of the LGBTQIA+ community or more angry for the impoverished Black teen who lived in neighborhood and education deprivation. To my surprise the author enabled me as the reader to get into everyone’s point of view and to experience empathy for all parties involved. I appreciated the format which engages young readers, because after all, this is about them and the world they are fast inheriting.

My heart broke over reading about the very different pains these young people went through up until the crime, and the painful aftermath. Richard had described his behavior as a prank and that he was egged on by his peers on the bus. He did not anticipate the skirt to burst into huge flames, severely burning Sasha’s legs. In the police interview, without benefit of counsel or a parent present, Richard claimed he was homophobic because he was trying to be pleasing and compliant with police questioningm, which is not unusual with minors in police custody. The police planted this term in Richard’s mind without Richard fully understanding the meaning or implication of his agreeing to saying this was his motive. This had the effect of adding hate crime aggravating factors to the crime he was charged with. Richard, who was tried as an adult, had pleaded no contest, and received a seven-year sentence. With this plea, the hate crime charge was ultimately dropped, and Richard avoided a possible decades long sentence.

For their part, Sasha suffered third-degree burns on their legs and endured weeks of painful treatment in the hospital. Sasha and their family also had to wonder how often in their life Sasha may become targeted as a member of the LGBTQIA+ and neurodivergent communities.

But there was also hope, healing, forgiveness, and compassion in the end, which gave me hope for both for the future.

Sasha and their parents to no avail had pushed prosecutors to have Richard charged as a juvenile as they saw the crime as a stupid, tragic, unthinking error rather than an aggravated assault. Richard had written genuine heartfelt apologies to Sasha and their parents soon after the arrest, which were not made known to the Fleischmans until two years after the fact. Richard ultimately had his sentence reduced to 5 years for good behavior while incarcerated.

If there is any takeaway about culpability, it’s on the criminal justice and legal systems, the lack of accountability of police interviewing minors, the inequality and deprivation in communities of color, and the schools that serve those students. If there is any takeaway about perspective, it’s on the fact that we need to assume a trauma-informed approach when dealing with anyone from a marginalized group. This book also talks about juvenile justice and juvenile detention centers. One of the statistics that really stood out to me was that 70 percent of youth in juvenile facilities have witnessed someone getting violently murdered or violently severely injured. The statistics of youth who have been sexually assaulted is about 34 percent and my belief is that it’s underreported.

When children are traumatized and in poverty how can we expect them to have developed moral compassion? And if they are compassionate, can we assume that they have been able to have impulse control? Can a teen who has felt unsafe in a deprived community resist peer pressure when pleasing the crowd has been the only way to be safe?

Children should never be interviewed by police without an adult advocate present. Again, institutions – namely law enforcement – are failing young people. There is a saying: “Be ruthless with systems. Be kind to people.” (Rest in power, Michael Brooks). It applies quite nicely in this case. Two very different kids deserve compassion for their lot, one because of gender identity and neuro divergence, and the other because of race and poverty.

One thing to keep in mind when thinking about hate crimes against the LGBTQIA+ community, while Sasha is White, the overwhelming statistics on crimes against these individuals is that most victims are trans women of color. I think of hate crimes from the lens of individuals from powerful groups victimizing others of marginalized groups because of that victim’s identity as a member of that marginalized group.

Perhaps we need to think of victim restoration as the goal of the criminal justice system. Perhaps we need to think more creatively about what is healing for the perpetrator and community as well. Perhaps punishment for many “crimes” need not be the end goal.

I recommend this book for any high school student and any educator who has a passion for creating safe supportive classroom environments which enable discussions that promote respect and dignity of everyone.