I never learned much about the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki growing up. It was a touchy subject. My father fought and was injured in the Pacific in WWII, and he lost his brother on Iwo Jima. I was taught in school and it was understood in my family that the atomic bomb ended the war; but I wanted to know more. I wanted to understand how dropping a weapon of mass destruction, deliberately killing tens of thousands of civilians, was justified.

The bomb was developed out of a race for time, out of a fear that Germany might develop a nuclear bomb first and win the war. Albert Einstein feared German weapons development and these fears certainly spurred the urgency of the Manhattan Project. My teachers were careful to teach American motivations for developing the world’s most destructive weapons. What was never included in my education concerning WWII was the role of racism in the use of these weapons. With our German enemy we directed our anger and outrage toward their leaders. By contrast, we targeted Japanese Americans with racial stereotypes that mimicked Nazi anti-Jewish propaganda. Japanese were caricatured with buck teeth, massive fangs dripping with saliva, and thick oversized glasses through which they leered with squinty eyes. They were further dehumanized as snakes, cockroaches, and rats, and their culture mocked, including language, customs, and religious beliefs. Anti-Japanese imagery was everywhere — in Bugs Bunny cartoons, popular music, postcards, children’s toys, magazine advertisements, and in a wide array of novelty items ranging from ashtrays to “Jap Hunting License” buttons. We felt the necessity to put Japanese-Americans into internment camps but German-Americans were never viewed with this level of suspicion or danger.

When I became an adult I engaged my father in stories about the war, including the worst aspects of WWII — from Pearl Harbor to the dropping of the Atomic Bomb. I knew he almost died at the hands of the Japanese, and I knew he lost his younger brother in the war. I asked for his blessing to travel to Hiroshima and Nagasaki to see if I could interview the remaining survivors, who were now elderly. To my surprise, he embraced my trip.

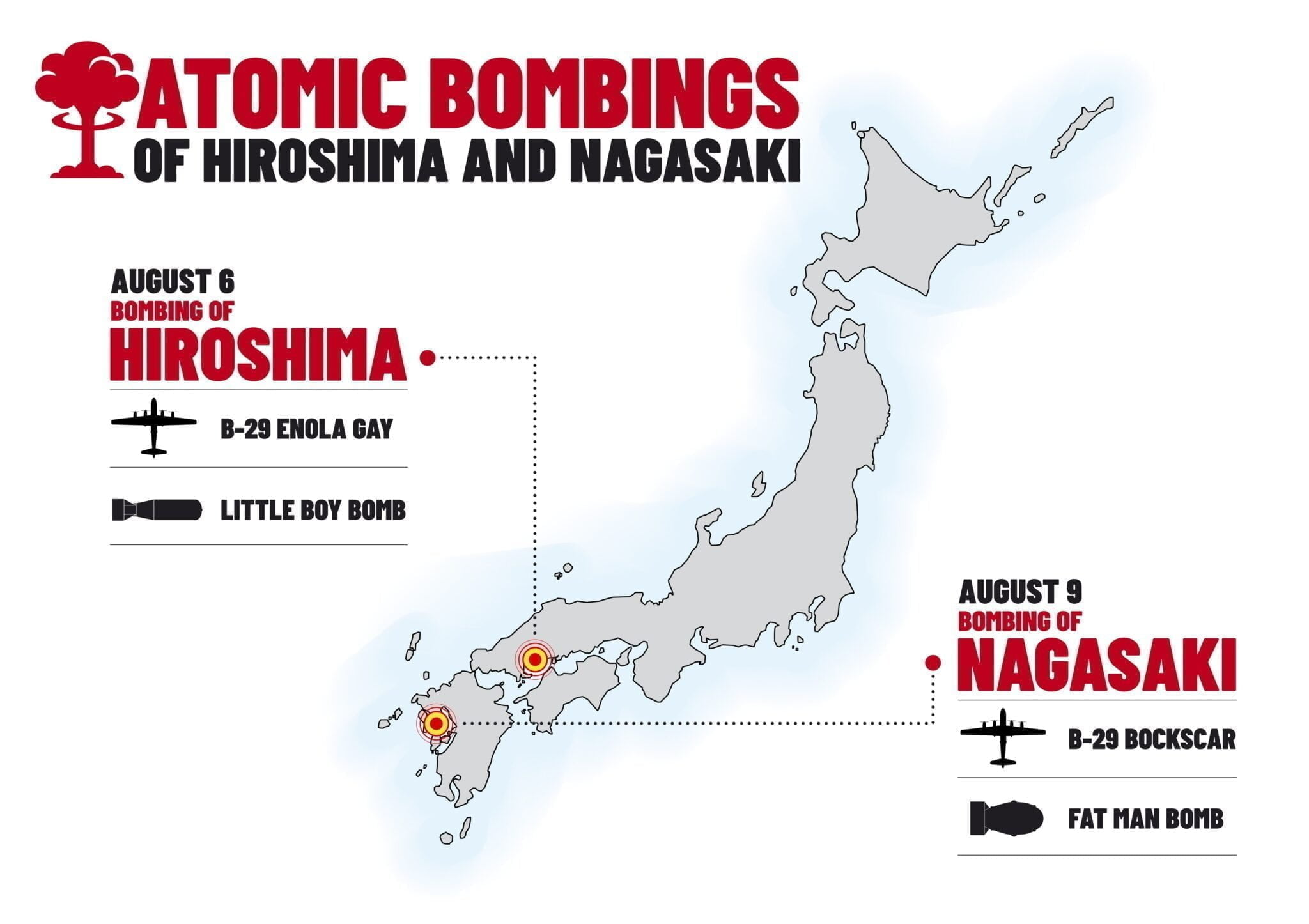

I first visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which is filled with pieces of everyday life salvaged from the atomic bomb, each tiny scrap of ordinary life a testament to the devastation. The first bomb was dropped on August 6, killing 80,000 people. I went to the school where 218 students were killed instantly — vaporized as they played or sat at desks — the epicenter of the bomb. I met with the American Marine who was the first photographer on scene after the destruction, who was forever changed by what he witnessed through the lens of his camera. He showed me many of the photographs that he initially sent back to the states but later learned were never shared with the public. He put those photos in a safe place and did not bring them out of hiding for fifty years. Joe O’Donnell has since passed away, but his book can be found here.

I then traveled to Nagasaki where 70,000 people died instantly just three days after the Hiroshima bombing, on August 9. I met with and interviewed dozens of Japanese people who survived the bombing in both cities, but were severely injured. They are known as nijū hibakusha.

Meeting the survivors and hearing their stories moved me deeply. They were all children when the bomb was dropped and they told me about their wounds, what it was like to try to find their parents in the chaos, losing their friends, losing their entire community around them. They spoke of the flies that laid eggs in their wounds, how they ate away the dead skin. Their stories felt like something out of a science fiction movie. People ran into the river and waterways because it was the only relief from the burns, from the heat of the atomic blast. Many died in the water. Many survivors were rejected by other Japanese as they grew up. They suffered radiation poisoning and if they wanted to marry and have children, they were discouraged from doing so for fear of birth abnormalities or other genetic defects.

These stories are rarely heard by an American audience. We seem to need the narrative of justification or revenge instead of trying to understand or include the other country’s suffering. It’s as if history only has room for the victor’s suffering.

I became involved with an effort to commemorate August 6 and 9 called “Lanterns of Hope.” Children would make lanterns, which would become a flotilla of candles glowing as they floated down the Delaware River. The event was to symbolize the fleeing of people to the water to relieve the burning in order to understand the devastating effects on innocent victims of the war.

So many lives were lost, so many of them children, and now, over 70 years later, we have the ability, the capacity to hear these stories if we allow our compassion to embrace them and vow never to use nuclear weapons again.

According to the World Federation of American Scientists, the world’s combined inventory of nuclear warheads remains at a very high level: nine countries possess roughly 12,700 warheads as of early 2022. And no one can envision what a hydrogen bomb would mean to human populations — their nuclear payloads hundreds of times larger than an atomic bomb.

As we commemorate the tragic, devastating events on August 6 and 9, let us work towards peace on a local level, on a national level, and on the global level. Let us dedicate ourselves to oppose violence in every form, to include the gun violence ravaging our schools and public life, which perpetuates more weapons sales as a means of protection — the same fear-based mentality that has led to internment, to war, to the development of each weapon of mass destruction that threatens our species and the planet itself.

This article was originally published August 5, 2022.