As a kid I read everything I could get my hands on: Thick Russian novels, trashy little romances, even how-to guides about taking care of exotic pets.

Why did I read so much? Well, first of all there wasn’t much else to do. There was no internet, no iPhones, no cable TV. In fact, where we lived in the backwoods of PA, there weren’t even any other kids to play with.

READ: Diverse Books Promote Self-Worth, Unity, And Empathy

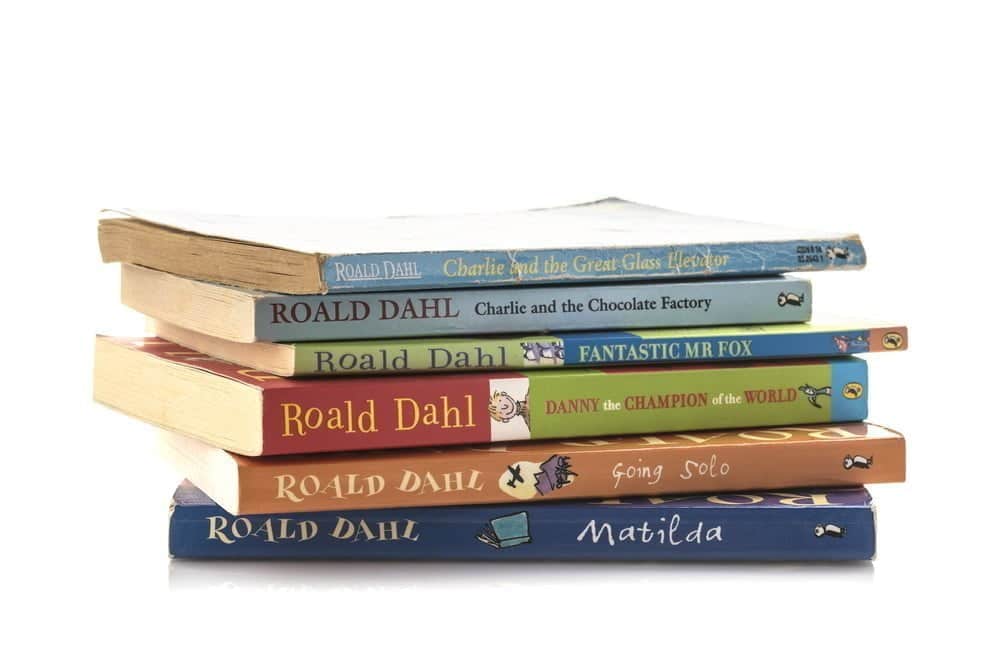

The kids I did encounter were mostly just during the 7 hours I spent at school each day. Kids who yelled antisemitic slurs at me, who laughed at me for reading so much, who burned my hair on the bus. Kids who seemed to me to be a whole lot like Mr. and Mrs. Wormwood in “Matilda,” or the aunts in “James and the Giant Peach,” or the Grand High Witch in “The Witches.”

But I didn’t just read because there wasn’t much else to do. I read because I wanted to understand what was going on in the minds of good people, of bad people, of other shy bookish people like me. I wanted to know what happened at the parties I wasn’t invited to, what caused good people to do bad things, what it felt like to be in a war or kiss a boy or love someone of the same gender. I wanted to know that quiet people like me could grow up to find their voice. I wanted to do all of that … safely, through books that I could shut, unlike the real-life bullies I could never seem to stop from hurting me.

I remember the first Roald Dahl story I ever read. I was in first grade and a kid had just told me my clothes were ugly. I remember the shame that burned my cheeks. That kid was right. My clothes were ugly. They were hand-me-downs from my much older male cousin that billowed around me like a deflating hot air balloon. I spent the rest of the morning huddled down in my seat, hoping no one else would notice.

Fortunately, it was my favorite day of the week, library day, the day we could spend a whole hour reading a book of our choice. That day I picked up Dahl’s “The Magic Finger.” “The Magic Finger” is a brutal story about a girl whose finger is an unpredictable weapon, doling out bizarre consequences to anyone who angers her. In the story, the girl transforms a family of heartless hunters into ducks who then become targets of their former prey.

It was a story of comeuppance for the bad guys, a story of the little guy fighting back, a story that had nothing and everything to do with me. I would never have dreamed of enacting the searing vengeance that Dahl’s characters did on their villains. But, I didn’t have to. Dahl did it for me.

READ: The Bucks County Courier Times Fails Readers With Its Book (Banning) Policy Editorial

Reading that book didn’t prompt me to take out my anger on the kids who bullied me, it didn’t make me use horrible words or hurt anyone – because that’s not what books do. Literature is a peek into someone else’s world, not an instructional manual of how to live.

Recently, the publisher Puffin Books has decided to edit and change Dahl’s original texts to remove offensive language and make the books more inclusive. Changes include removing the word “fat” from “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” and adding lines like “There are plenty of other reasons why women might wear wigs and there is certainly nothing wrong with that” to “The Witches.”

As a mother, I understand the concern about harsh language. As a Jewish person, I understand the worries about Dahl’s antisemitism that is woven throughout his books. But, as a reader, I am appalled.

First of all, our kids today have access to unlimited information online. Some of it helpful, much of it extremely dangerous. The truth is, the slow, thoughtful pace of books just can’t measure up to the thrill of scrolling and clicking. The danger of a child reading “The Witches” and, say, going out and making fun of someone wearing a wig, is minuscule compared to the reality of the harsh world of social media bullying. In fact, reading about how someone overcame bullying may well help them get through their own circumstances. I know it helped me.

Secondly, language and societal norms change. Literature is a good way to record those changes and discuss why they happen. Let’s be honest, all of our children have heard the word “fat.” Reading it in the context of a book written decades ago can prompt a conversation about why things that were once seen as acceptable are now recognized to be harmful.

Another important thing to note is that kids just aren’t reading much anymore. A study by the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) showed that the numbers of American 9- and 13-year-olds who say they read for fun on an almost daily basis are at the lowest levels since at least the mid-1980s. Given this reality, the idea of banning books or editing out words from beloved classics seems almost beside the point. Research has long touted the benefits of reading. Reading books strengthens the brain, builds vocabulary, reduces stress, helps alleviate depression and, maybe most importantly, dramatically increases empathy. At a time when right-wing parents and school boards are actively harming marginalized communities by removing symbols of support and allied teachers, it seems like we all could do with reading a few more books.