What are the most basic required actions that a congressperson in the House of Representatives must perform?

– One must show up for votes

– One must participate in committee hearings

– Most importantly, one must interact with the people they represent, both by addressing questions they raise about policy stances and performance; and by soliciting their feedback on the issues of the day.

Brian Fitzpatrick does a reasonable job with the first two (though one may have concerns with the way he votes, of course). But he fails dreadfully at the third. Fitzpatrick has a town hall problem.

You wouldn’t know that Fitzpatrick was failing by looking at his social media feeds. He’s always sharing pictures of his interactions with constituents. But those meetings are often photo-ops, they are almost always behind closed doors, and they are never made in the presence of our local media, who would provide accountability for any promises made at such meetings.

To be clear, we are not talking about those “telephony” events Fitzpatrick sometimes hosts. Any event where the lawmaker has the power to choose every question they are to be asked, screen their callers, choose to NOT include vocal critics, plant questions and talking points and dump callers when they ask something difficult – all things that Congressman Fitzpatrick has done – is NOT a town hall. Those telephony calls are nothing more than scripted self-marketing events.

And we are not referring to those captive audience high school events that Fitzpatrick calls “high school town halls.” If the attendees aren’t choosing whether or not to attend; if they can’t leave the event until the school bell rings; and if they aren’t even voters, then that’s not a town hall.

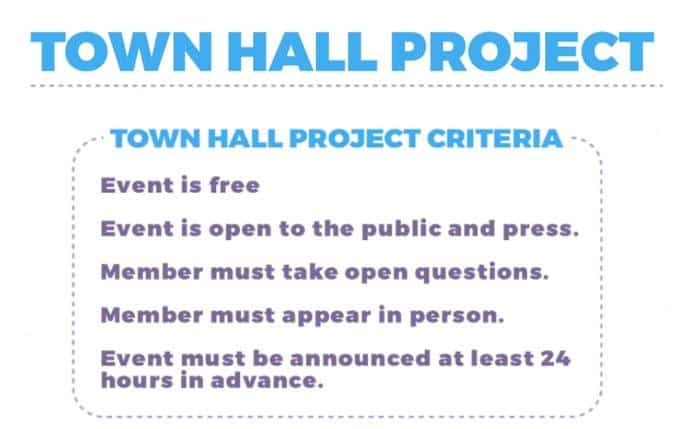

Real town halls met five basic criteria:

By that standard, Brian Fitzpatrick has never held a real town hall.

******

Not counting the weeks Congresspeople have off for Thanksgiving and Christmas, in 2023 representatives have 17 weeks where they are not expected to be in Washington, DC. Most of those are designated as “district work weeks.” And in decades past, all representatives were expected to use that time to meet with constituents and hold open town hall events. This has been a tradition for over 50 years.

When Congress passed the Legislative Reorganization Act of 1970, most of the changes did not involve scheduling. That bill introduced television coverage of congressional work, making committee hearings public and the addition of electronic voting for the members. But Time Magazine notes that “when the law passed, there were many younger lawmakers with children coming into Congress who wanted a more predictable legislative schedule and designated vacation times.” The same article says that “junior members lobbied senior members to install a recess in the schedule.” And those predictable breaks where lawmakers were expected to be in their home districts resulted in the tradition of scheduled town hall events when Congresspeople would gauge the feelings of their constituents and community members would question their representatives.

This tradition began to change in the wake of the Tea Party. The New York Times, in an opinion piece titled “The Tea Party Didn’t Get What It Wanted, but It Did Unleash the Politics of Anger,” points to the birth of the Tea Party as the start of the decline in Congressional town halls. The author, Jeremy W. Peters, evoked the summer of 2009 when the forces opposed to President Barack Obama focused their rage into protests against the Affordable Care Act:

“Lawmakers accustomed to scheduling town hall meetings where no one would show up suddenly faced shouting crowds of hundreds, some of whom brought a holstered pistol or a rifle slung over the shoulder. One demonstrator at a rally in Maryland hanged a member of Congress in effigy.”

Combine that collection of awful images with the ubiquity of cell-phone cameras and social media, and the sum of that equation is a collection of lawmakers increasing leery of bad photo-ops. That, along with the inherent lack of control when dealing with unscripted questions from the public, explains why some politicians, like our own Brian Fitzpatrick. are waving farewell to the tradition of the town hall.

There was, however, a short increase in the number of town halls held by lawmakers after the 2018 election. Many Democratic lawmakers took a Town Hall Pledge, promising to hold at least 4 open town hall events a year. But the advent of COVID made the logistics of in-person town halls impossible. And as we emerge from pandemic footing, many lawmakers are not interested in standing before their constituents and local media, and speaking extemporaneously.

There is no Representative more fearful of this than Brian Fitzpatrick. One need only look back to his one-and-only town-hall-ish event to know that is true. Held on August 22, 2017, (over 2000 days ago, but who’s counting), nearly 1,000 constituents expressed interest in attending. Fitzpatrick chose a tiny venue, and offered 120 seats, available by lottery. Doing so meant this event was not “open to the public,” thus breaking one of the minimum Town hall Project standards.

The winners of those Golden Tickets had to submit their question (yes, only one) in advance, and a moderator got to choose them, and ask them to our Representative. This also breaks one of the Town Hall Project standards, as there were not open questions Despite the event taking place right as Trump was implementing awful policies like the Muslim ban and trying to end the program that let Dreamers stay in the US, the moderator allowed only one question about then-Preisdent Trump, and even then he had to rescue the squirming, visibly uncomfortable Fitzpatrick. It was a debacle.

In the years since, Fitzpatrick has made excuses for not holding town halls. In his 2020 debate with Democratic challenger Dr. Christina Finello he referred to open town halls as “cattle calls” and blamed Indivisible (who to this day actively encourages him to hold a town hall) and people protesting him for why he would not hold future town halls.

Pennsylvania’s First Congressional District deserves better than this. We deserve a representative who allows himself to be informed by his constituents, so he can truly REPRESENT us. We deserve a representative who is willing to field open questions from his constituents, who is willing to explain to the people that have sent him to DC why he voted the way he did on particular issues, who is willing to make commitments in front of the press, who will hold him accountable for failing to meet those promises. Brian Fitzpatrick refuses to do this. And for this reason we call him an UNREPRESENTATIVE.

But Brian Fitzpatrick’s unwillingness to hold a real town hall is a concern that should be taken to heart by voters in Pennsylvania’s First Congressional District. We should count this as one of our priorities when we decide who to vote for – we should be willing to shun any candidate, regardless of their party, if they are unwilling to fulfill the basic job duty of holding public meetings with constituents and answering unfiltered questions in front of the media. Fitzpatrick’s continued tenure in office shows that this is a value we must nurture within our community. It is an issue we must regularly discuss with friends, family and neighbors.

On May 4, Indivisible Buck County leaders delivered a letter to Brian Fitzpatrick, signed by over 150 constituents, imploring our Representative to hold an open town hall before the people he represents. We hope he will do as we ask, but we aren’t holding our breath. But we are also asking you, the voters of PA-01, to weigh Fitzpatrick’s unwillingness to appear before us as a key concern when you decide who you are voting for in 2024. Because we deserve a representative who is willing to stand before the people they represent.