This article was originally published on Waging Nonviolence.

When people say, “I don’t understand how an Evangelical Christian could vote for Donald Trump,” I ask, “What have you done to understand them?” The usual response is something like, “Nothing, you can’t talk to those people.”

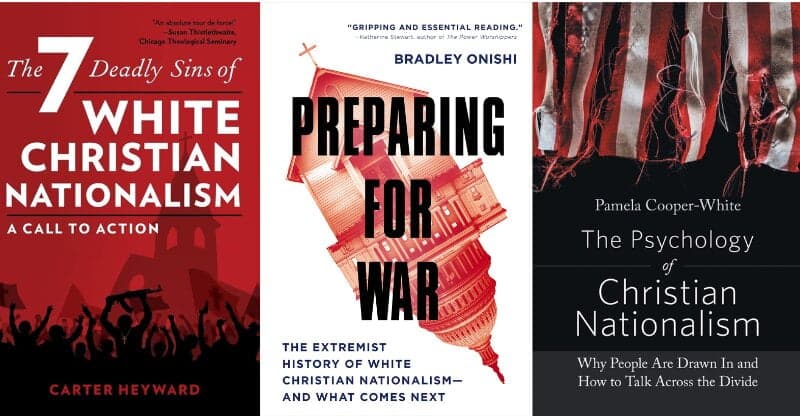

Three recently published books provide some perspectives on understanding the so-called Christian Nationalist movement and the people who identify with it. Using the Jan. 6, 2021 insurrection as a catalyst, each author explores the history, cultural context and possible future of the white-dominant Christian Nationalist movement.

The Rev. Dr. Pamela Cooper-White is an Episcopal priest and pastoral psychotherapist. In “The Psychology of Christian Nationalism,” she seeks “to understand who comprises the Christian nationalist movement and what they believe.” Her goal is to offer recommendations for how to “triage” when a meaningful conversation with Christian nationalist-leaning people is possible and when the situation is such that meaningful dialogue is not possible.

Using current sociological studies, Cooper-White provides a definition of Christian nationalism and statistics on how pervasive acceptance of those beliefs are. For example, 80 percent of self-described Evangelicals surveyed share some agreement with Christian nationalist viewpoints. The statistical content is clearly written so that a layperson can grasp it easily. “The Psychology of Christian Nationalism” could be useful for a congregational or community study group, especially in locations actively engaging with Christian nationalist activities.

Dr. Bradley Onishi was a youth minister in an Evangelical megachurch until 2004, and is now a scholar of religion, college professor, and host of the “Straight White American Jesus” podcast. After the events of Jan. 6, he started wondering whether he “would have been there” had he stayed in that community. In the ominously titled book “Preparing for War,” he is aware that former friends and church members were present that day.

Acknowledging that the roots of white Christian nationalism can be traced to the 19th century and earlier, both of these authors focus on the cultural and political upheavals of the 1960s as the catalyst for its growth. For Onishi, the nomination of Barry Goldwater as the Republican presidential candidate in 1964 was the starting point of a thread that continued to Ronald Reagan and ultimately to Donald Trump. That, in turn, brought the so-called Christian nationalist movement to the fore, resulting in the actions of Jan. 6. With that analysis, he concludes that Jan. 6 was not the “last gasp” of the movement, but an ominous new stage.

“Preparing for War” ultimately functions as a prophetic voice in the tradition of the Hebrew scriptures. After naming the individual and systemic forces that have brought us to our current dark situation, Onishi first asks, “Why didn’t we see this coming?” In that same tradition, he affirms that we are not without hope and provides several examples of movements working to build an alternative narrative. The hopeful outcome is not guaranteed without vigilant attention to the very real threat that white Christian nationalism poses.

“The 7 Deadly Sins of White Christian Nationalism” is a historical/theological/sociological exploration of the broader context and foundation of the movement. The Rev. Dr. Carter Heyward, an Episcopal priest recognized as a pioneer in the fields of feminist liberation theology and the theology of sexuality, is “writing to white Protestant Christians,” specifically “those who are moderate to progressive in their politics and spiritualities.”

The “seven deadly sins” referenced in the title are identified as: the lust for omnipotence, entitlement, white supremacy, misogyny, capitalist spirituality, domination of the Earth and its creatures and finally, violence. Each topic is explored in a separate chapter but the interrelationship of all is made clear.

By themselves, these chapters are a “heavy lift,” but the reader is not left without resources. In the concluding section, “Questions and Call,” Heyward writes, “The rest of this book is intended to help Christians think about what we can do. How can we strengthen the moral resistance to this authoritarian movement in our midst before it’s too late?” Part of the answer is a set of calls parallel to the chapters on the seven sins (e.g., entitlement/embodying humility). Each call provides analysis and reflection to help readers move toward the author’s intention to “strengthen the moral resistance.” Each call includes discussion questions for individual or group study.

Heyward is aware that readers might feel overwhelmed, or at least have questions, about whether it is feasible to “undercut and eventually disarm and defeat” Christian nationalism. To that end, the author offers this counsel:

- First, it will take time, more time than we personally have.

- Second, we need to be realistic how completely any of the deadly sins will ever be eliminated.

- Third, in the spirit of our ancestors (at their best) we must keep the faith (at its best).

Heyward’s book is an entry in the publisher’s Religion in the Modern World series, which explores how various religious traditions are engaging with the dynamic and changing role of religion in the modern world and examines how past changes reflect on today’s critical issues.

Will reading these books help someone “understand” so-called Christian nationalism? Through reading this trio of texts, I’ve learned much more about the psychology, history and theology of individuals involved in this movement and some of the influential organizations fostering the Christian nationalist movement. Do I now understand that movement — or, perhaps, is understanding the appropriate goal?

I’ve begun to think that awareness is a better goal than understanding, the latter of which is more passive and borders on acceptance. Awareness is a better starting point for increased learning and organizing to counter Christian nationalism. These books, and the growing number of investigative and analytical articles on the subject in various magazines and media outlets, are a good starting point for generating and sharing that awareness.

This story was produced by Fellowship Magazine.