The American right crossed a red line with its attack on the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. That is the central argument in David Neiwert’s detailed and sweeping new book, The Age of Insurrection: The Radical Right’s Assault on American Democracy. While that may be obvious to liberals (and non-MAGA Republicans), Neiwert goes further by contending that January 6 was not the endpoint of a radical right that has become increasingly menacing since the 1990s. Rather, it was the start of a new era in American politics in which the far right believes that a civil war is inevitable, and they have begun to act as such.

Neiwert introduces this argument with a not-so-subtle yet effective symbol: Julius Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon river in 49 B.C.E., which sparked a four-year civil war that ended in the fall of the Roman Republic and with Caesar becoming dictator. Neiwert circles back to this reference later in the book when he quotes Gavin Wax, president of the New York Young Republican Club, who declared ominously at a gala for his organization in 2022: “We want to cross the Rubicon. We want total war. We must be prepared to do battle in every arena . . . this is the only language the left understands.”

Neiwert, a freelance journalist who has covered rightwing extremism for thirty years, has written a book that is something of a compendium of his previous reporting. This is his tenth book; his others include one on conspiracy theories, one on the rise of the radical right under Trump, and another on the surge in rightwing militias under Obama. While The Age of Insurrection also covers this ground, the fresh research in this volume makes it a worthwhile, if unsettling, read. The fact that so much is covered here is the point: it’s meant to serve as a handbook—or a “toolbox,” as Neiwert calls it in his preface.

The aim of the book, Neiwert writes, is to make Americans aware of this dangerous new reality and to provide citizens with the knowledge they need to “understand the nature of what it is we’re up against: the ideologies and motivations and strategies of the ongoing far-right insurgency.” The Republican Party has become so radicalized, he asserts, that he doubts it can still serve as a “reliable partner in a viable democratic system.”

To bolster this last point, Neiwert cites a poll by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The poll, published in 2022, found that nearly 70 percent of Republicans believe in the “great replacement” theory—which proposes that white Christian Americans are purposely being replaced by nonwhite immigrants and Jews—and that nearly 50 percent believe the 2020 election was stolen. More than three-quarters of “very conservative” respondents agreed that the federal government “has become tyrannical”; and 53 percent of all Republicans polled believe the United States is headed toward civil war “in the near future.”

These are alarming numbers that cry out for further examination. What makes Neiwert’s book so effective is how comprehensive it is and how much detail he provides in his case studies. He takes us through all the major “patriot” and white nationalist groups—the Proud Boys, the Boogaloo Bois, the Oath Keepers, and more—and provides mini biographies of their leaders. He goes on to offer detailed accounts of the major incidents of rightwing violence in recent years (such as the 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville). He also dedicates entire chapters to the key conspiracy theories embraced by the radical right (like the great replacement theory), imagined and concocted enemies (like Antifa), and the major media personalities driving these narratives (like Tucker Carson).

One important driver of the modern right that I wished Neiwert had tackled is “movement conservatism.” Columnist Paul Krugman has repeatedly sounded the alarm in The New York Times about “movement conservatism,” which he defines as a tremendously influential, unified movement that includes the media empire of Rupert Murdoch and a wide array of think tanks and advocacy groups controlled by a small group of billionaires. This movement has been behind many of the GOP’s most disastrous policies over the years, such as climate change denial, financial industry deregulation, attempts to privatize social security and repeal Obamacare, and trickle-down economics.

While Neiwert does not mention “movement conservatism,” he does contend that astroturf groups have been funding some of the faux “grassroots” organizations and the strategies of America’s new hyper-radicalized right wing. One of those strategies, which has been indicative of what Neiwert calls the extreme right’s new “politics of menace and intimidation,” is a focus on local politics. Neiwert, in fact, dedicates his final chapter to this strategy because it’s been so effective—and because this is where elite funders converge with the “patriot” groups on the ground.

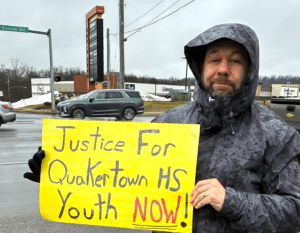

Neiwert digs up online chats by Proud Boys’ leader Ethan Nordean pushing a post-January 6 focus on local politics, and compares his comments with similar ones made by Steve Bannon around the same time in 2021. Later that year, the Proud Boys began turning up at school boards around the country, threatening members over issues such as critical race theory and bathroom use by transgender students. This strategy of intimidation has led to the resignations of countless board members, who were often replaced by conspiracy theorists and other rightwing radicals.

READ: Roger Stone Deserves More Scrutiny for His Role in the Events Leading to January 6

Moving on from school boards, the Proud Boys and their allies targeted town boards and city councils. Neiwert highlights Sequim, Washington, where a QAnon adherent became mayor and proceeded to force the retirement of the well-regarded city manager. In that case, however, the town fought back and booted the mayor. Neiwert uses the example to illuminate this strategy and push the left to be prepared to “out-organize” rightwing extremists at the local level.

He sums up the issue in this way: “The radical right’s strategy of targeting local politics proved so effective at driving ordinary civic-minded people away from democratic institutions and replacing them with conspiracist ideologues that it shortly became clear what democracy’s defenders are up against.”

On August 14, former President Donald Trump was indicted, along with eighteen allies, on racketeering and conspiracy charges over attempts to overturn the 2020 election results in Georgia. No U.S. President had ever been indicted before, but this was Trump’s fourth—the others were for his key role in the January 6 insurrection, falsifying business records to hide hush money payments, and for mishandling classified documents. Trump is viewed by many as the leader of America’s radical right.

In light of Trump’s ongoing lawlessness, it is impossible to read The Age of Insurrection without wondering what dire effect a second Trump presidency would have on this increasingly violent and unrestrained extremist movement.

Neiwert’s book is so valuable because it alerts us to the fact that anything is possible, and that without proper vigilance, a U.S. autocracy could be right around the corner.

This article was originally published in The Progressive and reprinted here with permission.