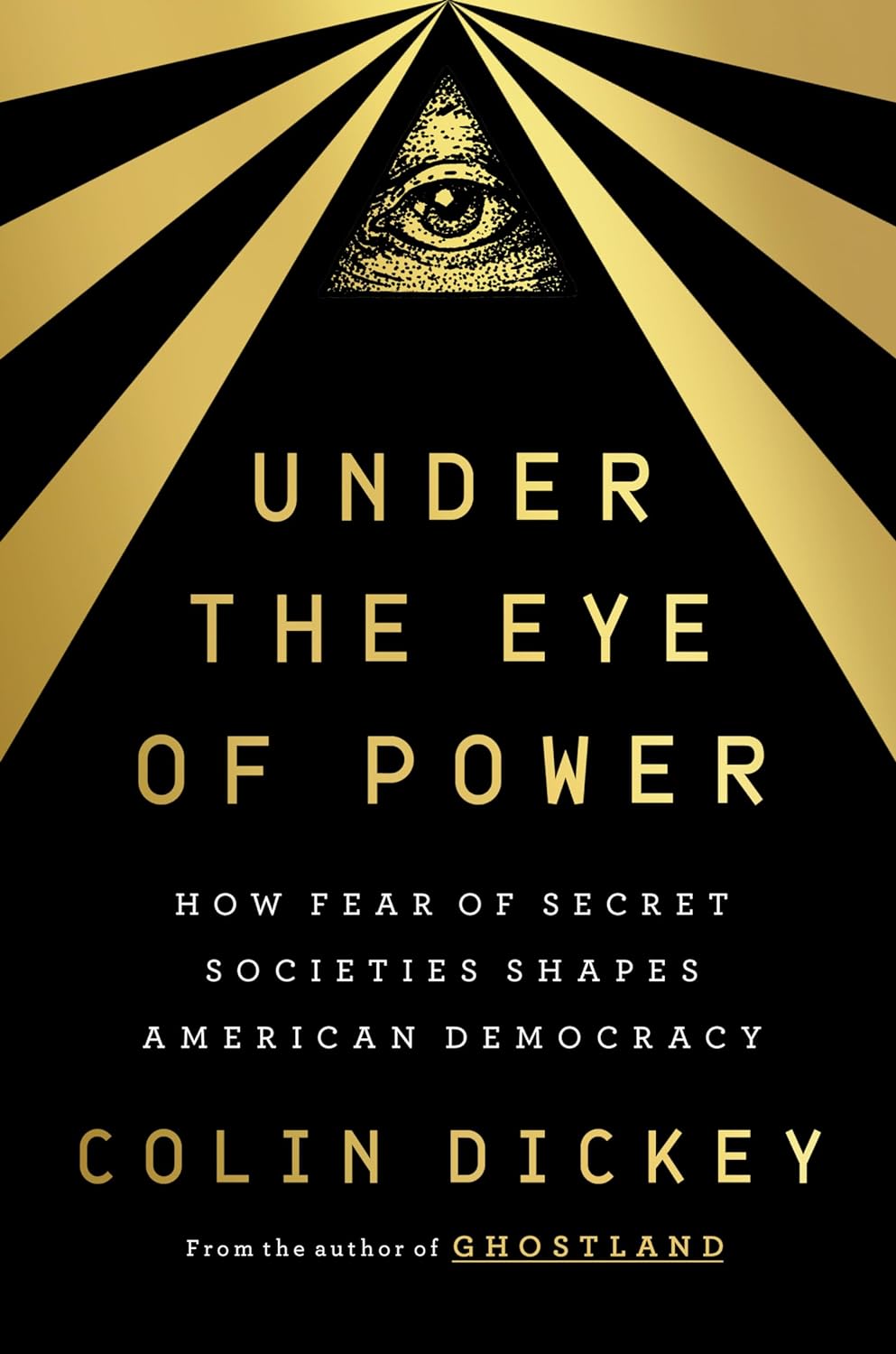

In Under the Eye of Power: How Fear of Secret Societies Shapes American Democracy, Colin Dickey argues that conspiracies occupy a central position in American history. “The United States was born in paranoia.” (1) Importantly, the author also makes the case: “To assume that conspiracy theories have mostly lingered in the margins of American political thought, policed by a sensible middle, only occasionally erupting into the mainstream, is to misunderstand the story entirely.” (10)

There are any number of explanations. Conspiracy theories are attractive because they can frame believers as heroes engaged in a moral crusade against evil. This has been true since the Middle Ages when the blood libel was invoked against Jews. Today, the moral crusade is one of the most important parts of QAnon. People are also drawn to conspiracy theories because they simplify complex events. It is tempting to discard inconvenient, subtle facts when one idea seems to make intuitive sense. As Naomi Klein observes in her book Doppelganger, we also devote significant time and effort to shaping and preserving our online personas and causes at the expense of constructive action to address many problems affecting the country.

Dickey challenges our fundamental understanding of America. From the colonial period onward, we have struggled with what the United States was versus what it could be:

“The American project had been conceived as something genuinely different, something that would stand as a beacon of liberty for the world, a perfect experiment. To face the harsh realities of its flaws and contradictions was a sobering proposition.” (117)

In effect, conspiracies have allowed generations of people to avoid some basic contradictions inhabiting the abstract idea of American exceptionalism. For example, the 18th Century Age of Enlightenment placed a premium on human agency informed by universally held natural rights. However, the reason did not resolve basic disparities in religious, economic, racial, or gender equality. The 19th Century witnessed the industrial age with all its attendant modern possibilities, while relying on the ancient practice of slavery. During the Cold War, America promoted the best principles of the “Free World,” while the military-industrial complex became increasingly entrenched at home.

READ: New Book Busts Historical Myths and Misinformation About the United States

At each turn, conspiracies have allowed us to sidestep a reckoning with reality. The collapse of the French Revolution into the Terror of the 1790’s was a serious cautionary tale, but one that instead spawned fear of the machinations of the Illuminati and Freemasons rather than the weaknesses of democracy. In the few short decades before the Civil War, as the country’s political system unraveled under the contradictions of slavery, Northerners and Southerners indulged in conspiracy belief. Free states openly worried about a conspiracy of Slave Power (75) dedicated to the wholesale reconstruction of the United States. Violent conflict, as practiced by John Brown in 1859, seemed a reasonable solution as fear metastasized into action. For their own part, Southerners perceived the abolitionists’ Underground Railroad (77) as a vast subversive network dedicated to the destruction of their way of life. These beliefs had an important function. “Again and again, conspiracy theories about secret societies became a way to massage these hypocrisies and smooth over their prickly surfaces.” (83)

Irony is everywhere in this story. Dickey speaks to the rapid growth of the John Birch Society (JBS) in post-World War II Southern California. In the late fifties, when Birchers first appeared, California was flush with defense contracts, particularly in Orange County. Yet this same area produced 38 new JBS chapters between 1958 and 1961, all pledged to resist a corrupt federal government deeply infiltrated by Communist agents. (228)

Secret societies have played an important role in this process throughout American history. Initially, groups like the Freemasons were sanctuaries where members could share unorthodox intellectual theories. Membership offered a sanctuary. Over time, however, organizations like the Freemasons evolved, as did their purpose. As a fraternal organization, it offered opportunities for social networking and economic advancement or, as Dickey puts it, “a means for the middle class to flex its muscles.” (53)

The purpose and membership of secret societies shifted along this axis in the 19h Century. Rather than acting as a sanctuary for the exploration of new ideas, later organizations like the Know Nothings served as a means to preserve traditional “Americanness” against the perceived threat of change. (47) Vested in the belief that outside groups, particularly Catholic immigrants, were incompatible with democracy, Christian morality, and American norms, they saw themselves as righteous defenders of the country. In 1854, Know Nothing-backed candidates won local, state, and federal (including 51 House seats) elections in more than a dozen states. (105)

READ: Can Education Solve Our Country’s Conspiracy Theory Problem?

Much of this legacy remains embedded in America today, with a few important additions. As Dickey observes, few people who covertly fight the good fight today are aware of this extensive, complex history. “Conspiracy theories, after all, feed on historical amnesia. They depend on your belief that what is happening now has never happened before.” (128)

Like the Know Nothing of the 1850s, modern day conspiracy theorists see themselves as a last-ditch defense of America: “both the GOP of Donald Trump and the progressive arm of the Left often speak of the American project as fatally doomed and needing an entire reboot from scratch.” (119) And, like Americans at the end of the 18th Century, many fear secular systems — from immunology research to analytics — running amok. “One way to look at the changes that happened at the beginning of the 20th Century involves a cultural shift in which new theories arose to displace human agency and the centrality of human existence…What connects the mutual reaffirming hatred of Marxism, of evolution, and of other forms of cultural modernity is this refusal to cede the primacy of human agency and intention.” (260) Dickey’s point brings to mind Dr. Ian Malcolm’s monologue in Jurassic Park about the arrogance of science and the power of chaos.

Lastly, Dickey points out two important characteristics of contemporary conspiracy belief. The first regards the end result of the constant accumulation of conspiracies in the social discourse. “What has happened by the 1990s is that there are no longer distinct moral panics. It’s become syncretic: everything gets folded into the same morass, without distinction.” (283) Layer upon layer of conspiracy theories have produced an embedded distrust in authority without much in the way of clear distinctions, political, ideological, or otherwise. Recent polling speaks volumes on this issue. An April 2021 Morning Consult survey noted that 49% of Americans supported the QAnon idea that “the world is run by Satan-worshiping pedophiles, including left-wing politicians, Hollywood celebrities and religious figures.” (308)

READ: Understanding Why Christians Are Seduced by QAnon and Conspiracy Theories

At the same time, many modern-day conspiracy theorists no longer have to rely on secret societies to protect and promote their beliefs. Powerful figures, from Michael Flynn, to Ginni Thomas, to Donald Trump lend agency to what used to be the lunatic fringe. They also inspire fledgling conspiracy theorists to increase their own status within this insular community, earning what Dickey calls –“a strange form of cryptocurrency”- as they advance through the online ranks of true believers. (284)

“Ultimately, people are not looking for answers; they’re looking for permission.” (287)

Under the Eye of Power serves as an important lens for America right now, particularly as election season unfolds. Regardless of the race — for school boards, state legislatures, or the presidency — we are witnessing conspiracies hiding in plain sight to a degree not seen since the prelude to the Civil War. A better understanding of our own history of conspiracies might be one of our best tools for 2024.