On one night this week – all across the nation – public housing case managers, mental health professionals, shelter directors and a legion of volunteers will canvas the back alleys and wooded areas of the country in search of families and individuals experiencing homelessness. In Bucks County, that night was Tuesday.

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development calls this experiment the Point in Time count – PIT count for short. The federal government’s once a year count of identifiably unhoused individuals is supposed to provide Congress with a cross country snapshot of the population living in the most despicable of circumstances – ostensibly so that the nation’s representatives can then allocate funding to alleviate the problem.

Critics of the count insist that one night’s (or in the case of Bucks County – one day’s) search of public spaces and homeless shelters can’t possibly identify even a fraction of the people in the U.S. experiencing homelessness. At the time of the count, only those who are discoverable, available and willing to be counted are included. Well-hidden individuals, folks at work or school, and people sequestered away in temporary accommodations – like motels – aren’t counted.

For those who are identified, little is known. The federal government requires minimal data about unhoused individuals, limiting information gathered to housing status and approximate age of the individual. Various counties across the country ask for additional information. The 2024 Bucks County questionnaire includes inquiries about gender and sexual orientation, domestic violence/sex trafficking, current health status, and whether the person has pets or is elderly. Other demographic information including employment, school attendance, and veteran status are not required.

With the information gathered, the federal government determines housing assistance allocations for each county and parish in the United States. Based on the numbers, Bucks County may receive more or less funding than they had in previous years. The additional questions asked inform the local housing agencies about aspects of the unhoused community. The county then decides what assistance to prioritize when allocating the funding.

READ: In Bucks County, a Small Church Strives to Help the Ones Around Them

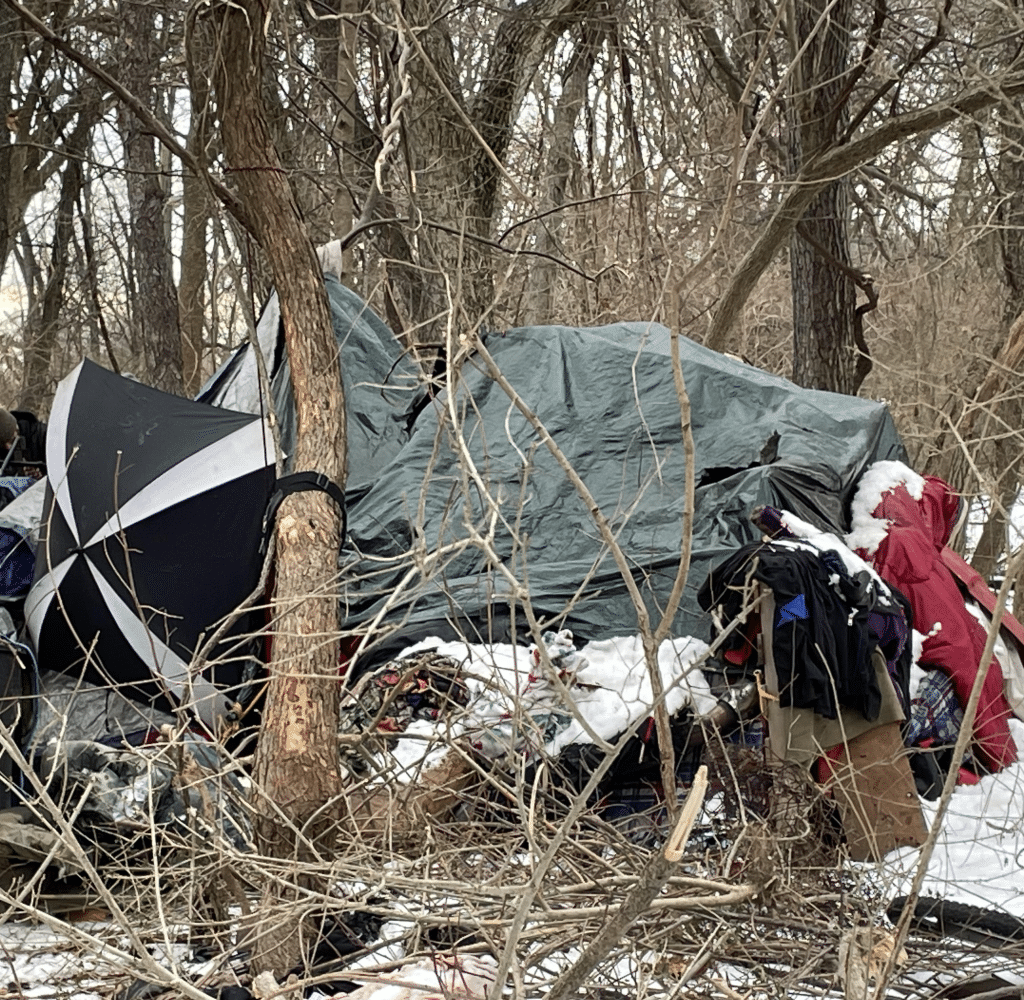

In addition to other advocates, the staff of Family Service Association of Bucks County, Brandi Stewart, Cinquetta Fisher and Sayon Kplepo, were sent into the field on Tuesday. These outreach workers provide healthcare on the street, in the woods, wherever they find unstably housed individuals in need of urgent care, primary care, or dental health care. An RN, Stewart knows what they do saves lives and saves the community money, as their street medicine reduces the number of Emergency Room visits each year. “We go into the encampments and help people stay healthy.”

Stewart sees an aging population on the streets of Bucks County. “Our elderly population has grown significantly. The oldest person [in homelessness] we’ve helped was ninety-two. Now the oldest patient we have is eighty-nine. We have a senior housing crisis.” Of course, her street medicine patients vary by age. “We had a gentleman on hospice for heart failure at forty-one. Many of our clients are medically frail people. I have a triple amputee, patients in need of dialysis, chemotherapy – people at great risk of death. Our job is to lower the load on the ERs and eliminate preventable death.”

She likes her work. Especially because she sees real healing in the population she serves. “Compliance for the unhoused who get outreach is better even than the people who are housed. I’d say ninety percent of ill people on the street want to take their medicine. We give them lock boxes to hold their prescriptions and reminders,” so they don’t forget.

But people need more than medicine. “Often the most challenging aspect for diabetics is food scarcity. Foods that ‘last forever’ outside, generally contain large amounts of salt and sugar. Food stamps – the nickname for the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) – don’t cover hot food. It’s so much work to watch a diet,” when living rough.

“You know what we hear most often? ‘Thanks for never giving up on me.’ Or ‘You saved my life.’ We deal with really good people who have experienced really terrible trauma. We treat everyone with respect. And we should – because they’re human beings.”

READ: Starve or Quit: Some College Students’ Only Options

Daily, Stewart sees the effects of their work and cautions against stereotyping folks in need, “A lot of our clients go from huge diabetic wounds to going to wound care. We help them stay compliant with their healthcare and we do a lot of harm reduction. I haven’t met that stigmatized version of a homeless person. Our clients are kind. Loving.”

While acknowledging the existence of some drug using clientele, she’s quick to add that there are drug users who have homes too. Her goal is to prevent death to anyone she encounters. She and the other healthcare providers carry Narcan for overdose victims. They also distribute Xylazine and Fentanyl test strips. “People want those tests. Xylazine is a horse tranquilizer that causes massive necrotic wounds. People don’t want those wounds from Xylazine. That’s a big part of what we do. Harm reduction, education, and outreach. A lot of our [addicted] clients want to get into rehab.”

During the count – after stomping four miles through ankle deep snow – Stewart added with a sigh, “If you don’t have a nest egg, then you’re two paychecks away.” The Family Service van she drives is stocked with supplies – over the counter medications, masks for performing CPR, dressings for wounds, and preventative measures, too. “We’ve had Narcan for a while now. And the other drug test strips.” But lately the Street Medicine team has added nutritional supports, “We carry Ensure and Boost – it’s expensive – but there are so many old people now.”

As darkness falls on Bucks County, the street teams leave the woods and parking lots and counting resumes at the shelters. Because HUD schedules the count for one of the coldest months of the year, the annual count includes the Code Blue shelter – hosted by the Coalition to Shelter and Support the Homeless (CSSH). A roving emergency shelter, its location varies by month. From December through March, Code Blue is hosted by four different churches.

CSSH Executive Director Nicole Buckley-Mormello and one other employee are the only paid staff. Each shelter night requires a minimum of 14 volunteers – necessitating many times that – over the course of the winter. If the weather becomes unseasonably warm, or the requisite number of workers have not volunteered, the shelter remains closed.

On the night of the count, dozens of people experiencing homelessness descended on Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Church in Doylestown. A van collects people at locations in Warminster and Doylestown then delivers them to the hosting church. The guests begin to arrive at 7:30 p.m., given an air mattress and bedding, a hot meal, a place to charge phones or other electronics and a warm coat or other incidentals, as needed.

READ: Proposed Law Aims to Keep Pennsylvania’s Homeless Students in School

In the church kitchen, volunteers prepare and serve a hot dinner. They’ll do the same the following morning and make brown bag lunches for their guests to take when they leave. Our Lady of Guadalupe parishioner, Rita Lynch, has volunteered in the kitchen since before the pandemic. She’s dedicated – showing up during the covid outbreak even before vaccines were available.

Helping has been part of her life since years earlier when Lynch discovered that several people were living in the woods behind a local grocery store, “I want to contribute because I’m blessed with so much more than they could dream of having.” Volunteering seemed pretty straight forward when she became a regular cook for the shelter and other community meals organized by CSSH, “My only surprise was how much they are like me or anyone I’m related to. When I was a young single mom … I could have been any of these people, any number of times.”

In February the shelter will move to St. Paul’s Lutheran Church, and Lynch will follow. “I see appreciation and gratitude and that just warms your heart.”

Vicki DelCasino, Street Outreach Case Manager for Bucks County Opportunity Council, marvels at the kindness and generosity of the volunteers who give so selflessly to help the desperately poor, “Our local volunteers are so hospitable and kind. But when it comes to our representatives, when we need more shelter or housing assistance, we get told ‘not in my neighborhood.’” And while the official totals of how many identifiable people experiencing homelessness showed up in this week’s count won’t be available for months, some people who live in affluent Bucks County think there isn’t that kind of poverty in their region. For those people, DelCasino has a simple message, “Get your head out of the sand.”