Black History is a history of resistance and liberation. This may explain why, in part, we’ve seen such a whitelash and a war against Black studies – and Black history in general – being waged by right-wing reactionary groups like Moms for Liberty, and Republican lawmakers.

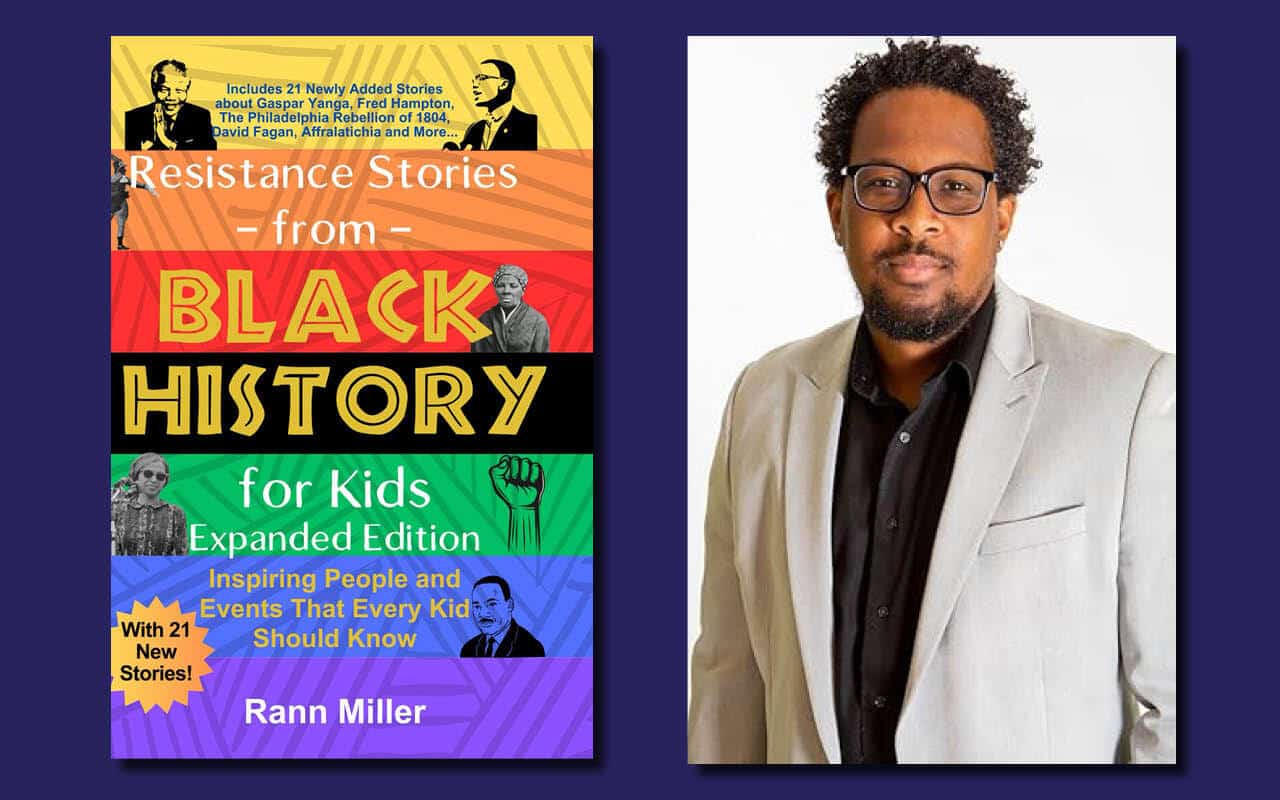

Today I am joined by Rann Miller. Rann is an author, educator, and advocate for the education of Black children in the Delaware Valley Region. His experience as an author and writer spans over ten years and his experience in both K-12 settings and higher education settings spans over 15 years. As an educator, he’s served in various capacities, including faculty and administration. His current role is Director of DEI Initiatives. He is the author of the recently released, Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids.

Rann is also an opinion columnist for Atlanta Black Star. His writing has also appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Washington Post, Education Week, Salon, and a host of other platforms. Rann is a graduate of Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey.

You can also keep up with Rann at linktr.ee/rannmiller.

[Also listen on Apple, Spotify, iHeart, and Podbean. Transcript below.]

Host Cyril Mychalejko’s 5 Reading Recommendations to Further Shine a Light on the Issue:

- How the Word Is Passed: A Reckoning with the History of Slavery Across America, by Clint Smith

- The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story, by Nikole Hannah-Jones

- Force and Freedom: Black Abolitionists and the Politics of Violence (America in the Nineteenth Century), Kellie Carter Jackson

- For 150 Years, Black Journalists Have Known What Confederate Monuments Really Stood For, Donovan Schaefer

- Teachers, Students and the Central York Community Defeated a Racist Book Ban in Their School District, by Cyril Mychalejko

ALSO LISTEN TO:

- EPISODE 2 – The Merchants of Deception: The Dark Money and Front Groups Behind School Privatization, with Maurice Cunningham

- EPISODE 6 – The Right’s Long War On Public Education, With Jennifer Berkshire

- EPISODE 7 – Understanding Backlash Politics And Religious Conservatives Inciting School Board Wars, With PRRI’s Melissa Deckman

- EPISODE 8 – Students and Teachers Fight Back Against Book Banning in Central York, with Christina Ellis and Ben Hodge

- EPISODE 11 – Unmasking Moms For Liberty’s Extremism, With Olivia Little And Diana Leygerman

- EPISODE 21- Understanding the Nation’s Mounting Book Banning Crisis in Public Schools, with PEN America’s Sabrina Baêta

TRANSCRIPT

Cyril Mychalejko: Before we speak about your book, Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids: Inspiring People and Events That Every Kid Should Know, can you tell us first how and why you became interested in history?

Rann Miller: I remember as a young student learning a number of different things. And I think it really started, I’d say about like eighth grade, I really enjoyed learning some of the history of the United States, although it wasn’t really a full picture. But I remember applying to high school, I went to a Catholic high school and part of the application process was picking certain electives to take.

And one of the electives that I wanted to take was called World and European History. I got to take it my 10th grade year at the school. And in the middle of learning all of that stuff, I had asked the question, why is there not a African history course? Why is there not a history course on African American history? And no one at the school could really give me an answer. And no one at the school really did anything about it.

So, when I became a teacher, for me, it was always about teaching the things that I did not know. And so that created this world of really exploring … and that started in college with my college professor. So they really gave me the tools to dig in and find out information. And so that’s something that I’ve always continued to do. And it served me well, certainly served my students well with regards to the information that we cover in our classes.

Cyril: So why did you decide to write this book, and why the focus on resistance?

Rann: So I’ve been wanting to write a book for a while with respect to history, but never quite understood where I wanted to go with it. But it occurred to me that resistance is something that we don’t often speak about. It’s something I always talk about in my classes and something that I try to focus on just to make the point that African-Americans were complicit in their liberation. But considering all of the things going on in our country, considering the war against Black Studies, the war against Black history, I thought that it was really a great time to put something together where we really explored a part of our history that we don’t often talk about. And it also gave me an opportunity to continue in the tradition of scholars that have come before me, the Carter Woodson’s, John Henry Clark, Arturo Schomburg, where African-American history starts in Africa. It does not start with the enslavement of our ancestors. So I wanted to really put a book together that made that point clear, but also made the point that Black people had a huge, if not major, if not primary role in the liberation of ourselves.

Cyril: That’s something I actually wanted to talk about. Your book, unlike, especially like school textbooks, centers Black people as the protagonists of their own story written in the active voice? And so this is a need that you saw based on your own experiences as a student?

Rann: Yeah, yeah, absolutely. As a student, you know, you learn the basics, right, about the United States, the formation of the United States, you learn about, for example, of the colonies forming and this new way of being happening and then this idea of revolution for the sake of trying to respond to tyranny. We don’t often speak or teach or learn about the United States being a white settler colonial project. We don’t often discuss the reality that all of this land was taken away from the indigenous people who lived here. We don’t often teach or discuss the real reason behind the Revolutionary War and having to do with the fear that Great Britain was going to abolish enslavement. And so abolishing enslavement in Britain meant abolishing enslavement in the colonies as being under the control of Great Britain.

So we don’t talk about those things.

And we don’t talk about certainly how African-Americans understanding that at the time, how they went about making their decisions for how they were to liberate themselves under those conditions. And so, you know, as a student learning the former and not the latter, it really struck me when we came to say Black History Month, like right now, and you hear all these stories say, well, why aren’t we learning that in our regular classes? Why is that relegated to one month out of the year?

Certainly that’s not what Dr. Carter G. Woodson intended, but it really had gotten me into a place of wanting to do more discovery and actually utilize that as inspiration for putting this book together. One of the inspirations for putting the book together.

Cyril: So the history that you write about is a global history, which is something that you mentioned earlier. It starts off in Africa, in Kemet, or what would be recognized today as modern day Egypt. Why did you decide to start your story there?

Rann: So I wanted to go there because there is a history of devaluing African people in that part of the region, particularly when we know that the Egyptians influenced heavily Greek civilization. And then, of course, Greek civilization was used for Roman influences. And so when we speak of Egypt, when we speak of Kemet, historically there have been challenges and debates as to say whether or not those folks were African people. And so that was a centering of Europeans as to say that their culture and the beauty and the majesty of what we are as the United States democracy and all of these sort of things, it did not stem from a Black people. But in reality, we know that the people of Kemet were Black. They were Black African people who descended from lands further south from them. And Kemet means the Black land. And so I wanted to really begin early in the book with that, just to say that for all of the displaying of the United States as being the

descendants of the Greeks, the Greeks got a lot of their culture, a lot of their influence from Komet and Komet is in Africa and the people were black. And so I wanted to make that point really to establish the idea of where we really find our lineage, whether it’s with respect to politics, whether it’s respect to religion, much of what we are stems from Africa.

And unfortunately, because of the Eurocentric centering, we have not told that story accurately.

Cyril: Later in the book you take readers on a journey to Haiti to learn about the Haitian Revolution and the country’s independence. How did these historical events impact the United States?

Rann: The Haitian Revolution was integral to the United States and particularly the history of Manifest Destiny, if you will, not to say that the Haitians were for it, but it’s just to say that the United States took advantage of a situation. The United States had tried to purchase New Orleans for a long time when it was under the control of the Spanish. They tried to purchase it when the French regained control. They tried to purchase it from Napoleon and Napoleon did not accept the offer. I think it was, I might be getting my numbers wrong, but it might have been $10 million for the city. He didn’t take the money and things changed when the Haitian Revolution came about. Napoleon had to divert resources to Saint -Domingue, which was the name for Haiti at the time under the French. And that required that he take away resources from other places.

And unfortunately for him, he could not dedicate his time to the Louisiana territory in the United States. And as a result of having to dedicate many resources to Haiti, because those Haitians were a thorn in his side, so much so that in France, he was teased. He was, you know, Toussaint Louverture was called the Black Bonaparte. And Napoleon was so incensed. He said, I will do anything, I’m paraphrasing, to make sure that these Black people do not take over and that Black people don’t see themselves able to do what they’re doing in Haiti. And so that opened the door for the United States to say, hey, if you’re not looking at this territory, if you’re not doing anything with it, we’ll take it off your hands. And I believe they paid for the entire territory $15 million, where they were going to spend 10 on New Orleans, but now they got everything. And so the Haitian Revolution really made it absolutely possible for the United States to get the territory that it has those states that we know to this very day. And nevertheless, the United States still at the time abhorred what was going on in Haiti. The French enslavers that came to the United States. They went to New Orleans. They came as north as Philadelphia, they went to South Carolina, they were afraid, definitely afraid, and the United States was in the position to benefit, but also make sure that they did not allow for what was happening in Haiti to happen at its borders.

Cyril: So that was essentially the thread of a good example for Black Americans, Black enslaved Americans living at the time. That’s what Haiti was.

Rann: Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. In fact, many Haitians, for example, that traveled to South Carolina, those Haitians were in contact and talking to Denmark Vesey, who was planning an enslaved revolt. There were a number of Haitian folks that came to Virginia and were in contact with Nat Turner as well. So, one thing about the Haitians, and I speak about in this book, that it wasn’t just about their own liberation, but about the liberation of African people throughout the diaspora. And they were looking, in one of the chapters, I talk about how they were looking to work with the Mexican government, you know, under the leadership of Vicente Guerrero, the first Black president in North America who happened to be in Mexico. And over the years, even after his assassination, the Mexicans were working with the Haitians. They were looking to liberate Cuba.

If it weren’t for Spain promising the recognition of Mexico as a result of talking to the British and the United States, who wanted nothing to do with that. So the cool thing about what Haiti had done was they weren’t just trying to liberate themselves, but they were trying to create allies amongst free Black nations throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Cyril: You brought up revolts. Let’s talk about that a little more. In your book, you cite a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center noting that students have an incomplete, if not distorted understanding of the history of slavery in the country. One area is that this belief that freedom was something given to Blacks, whether from abolitionists or the federal government. But again, going back to the idea of Black people as protagonists in their own history, can you talk about Black slave-led revolts as a form of resistance in that journey to freedom?

Rann: Sure. Herbert Aptaker, the Marxist historian, talked about the various forms of resistance. And he wrote a number of scholarly articles, as well as books, that I reference in my book about the sort of history of revolts in the United States. And according to Dr. Aptaker, there are roughly 250 documented revolts of enslaved Africans in the United States. And that’s just what’s documented. There may be more that we’re unaware of. And so I think that there’s this idea that African-Americans, their point of resistance was simply to run away. But revolt was something that happened fairly often, more often than is likely discussed. And not only in Southern states, revolts happened in Northern states as well. There are certainly the New York City revolts of 1712 and 1741. There are certainly a number of revolts that happened in the state of New Jersey where I’m located, in North Jersey in particular. So African-Americans revolted regularly. It wasn’t something that was rare. It wasn’t something that did not happen.

And even revolt in the sense of fighting in war. African-Americans utilize war as an opportunity to revolt and fight against the United States. Often in war, we talk about African-Americans who fought with the United States to gain their freedom, but we never discuss the Africans who fought against the United States. And I’m namely, specifically thinking about the American Revolution, those Africans who fought with the British early on. If it weren’t for those Africans fighting with the British and beating the United States, George Washington would not have allowed African Americans to fight with the Americans. I’m thinking about the war in 1812. Certainly the African-Americans fought with the British again to get their freedom as well. And so African-Americans were not afraid to utilize the violence that was perpetuated against them for the sake of their own liberation, for the sake of their freedom. And they did this relatively often, but again, it’s something that we don’t speak about. It’s something that we don’t talk about. We only mention, you know, your Nat Turner’s, again, Denmark Vesey, whose revolt was cut short. Gabriel Prosser, we think about, whose revolt was cut short.

But we don’t make those real discussions about that. Even to the extent that I speak about in the book, the Black Seminoles, we don’t talk about what those revolts look like when you have African-Americans connecting with Indigenous people through ethnogenesis to create a new group of people who revolted against the United States. In fact, the Trail of Tears, the removal of indigenous folks didn’t go quietly, and that had to do with Africans, African-Americans fighting with the indigenous in Florida, making it very difficult for the Trail of Tears, the Indian Removal Act to be made complete. And these wars, these seminal wars went on for, you know, close to 20 years before the United States was successful in its desires to have Manifest Destiny.

So that point is just to say, we need to speak more about revolts of African Americans because that’s as much a part of our story as a country as anything else.

Cyril: Another resistance leader you write about is Harriet Tubman. In fact, you call her the greatest American ever. Why do you think she deserves that title?

Rann: I think she has earned that title based on the work that she has done. Not only did she utilize her gifts and talents to free herself, not only did she do so to free her family, but she freed a number of enslaved Africans going back and forth. Not only that, but she worked.

in various places in the North, in Philadelphia she worked, she worked in New Jersey, South Jersey particularly, to save money to make those trips. Not only that, but when she made those trips, she did so with weapons on her to not be captured again. She had connections, knowing the land, knowing the people, particularly if any indigenous folks. Not only that, she served in the Civil War. She served as a spy. She served as a nurse. She also led a group of Black soldiers into battle where she did battle. Harriet Tubman represents the overall spirit of liberation, not just for African-Americans, but for all people.

And it is no accident in my mind that it was a Black woman who led this. And for me, who she was, what she stood for, her mission. She did not die rich. She did not die, with a bunch of wealth, but she was able to save her family. She was able to build a home for them in Canada. She was able to try and help others.

I just think that she is the greatest American who ever lived, if there ever was one, due to the work that she has done. And, you know, I think back to the talk about putting her on the $20 bill. That’s something that I don’t believe, not to speak for Harriet Tubman, God rest her soul, but she would want … she fought against the mechanisms of racial capitalism. Her work was all about that. And so to be put on a dollar bill is to limit the impact that she’s actually had.

I don’t think that we quite reverence Harriet Tubman in the way that we should considering her battles as a person being hit over the head as a child … that kind of went along with her throughout her life where she had moments where she blacked out the tragedy that she faced in her marriage, that not being successful. Nevertheless persevering through all of the challenges to do the things that she’s done. She’s absolutely an amazing, amazing person that we should give more reverence and celebration to.

Cyril: Let’s talk about another Black woman resistance leader. The teaching of Rosa Parks, I think serves as a perfect example of the whitewashing and sanitizing of history. Despite what we’re taught, she wasn’t just a tired seamstress who wouldn’t move from her bus seat. She was so much more. Can you tell us about her radical and activist background that gets left off the pages of history?

Rann: Rosa Parks was a member of the NAACP in Montgomery and the work that had been done where she sat in the bus, right, sat at the seat, that had been organized. And this isn’t to take any credit away from her, but it’s just to say that these things don’t happen in a vacuum. I think that the teaching of Rosa Parks has been a disservice because again, when we limit it to Rosa Parks being the individual to make a decision, we don’t give credit to the groups and the activism that helped to create that situation. And when we don’t do that, we fail to make the connection between how organizing and institution building is what fights institutions.

It’s very hard for an individual to fight an institution. And even if there is some sort of victory, the victory may be short lived, the victory may be compromised, right? Rosa Parks was a part of an institution, the NAACP. And those folks, the NAACP, have been able to fight major institutions that were racist on behalf of Black people. And so there was an organized effort amongst numerous Black women who sat on the bus. Rosa Parks was not the first, but she was the one to get the sort of publicity that started what we knew as the Montgomery Bus Boycott. And the craziest thing about the story is she wasn’t even at the front of the bus. She was in the front of the colored section of the bus. And the white person that was looking to sit was wanting to sit in that front area of the colored section because the white area was taken and certainly what Rosa Parks had to do was go all the way to the back. And they did that intentionally. It wasn’t done, you know, haphazardly. It was done that way intentionally to prevent this idea of rebel rousing because if you have her sitting in the white section, it can be said, oh, you knew you weren’t supposed to do that versus her sitting in the colored section.

She was sitting where quote unquote she was supposed to sit and yet she still faced the discrimination which makes it even worse. So again, that was with intention. And also it wasn’t just what she did in Montgomery, but there’s also the work of when she moved to Detroit. She continued to do civil rights work. Notably, she worked for Congressman John Conyers specifically helping him with putting together the legislation, the bill for reparations. In addition to that, she helped him get elected in the first place, making a call and working with Dr. King to come up to Detroit to campaign on his behalf. Rosa Parks, her story is not completely told either. We’ve limited her to one moment in time when in reality there’s so much to who she was as an American as well.

Cyril: And she also trained or participated in trainings at Highlander Center as well. Can you tell us a little bit about who the deacons of defense were?

Rann: Yes, so the Deacons of Defense were members of various Black church congregations in the South. At the time, you had a number of unfortunate events happening at churches, bombings at churches, you had cross burnings at churches, and much of the

activism that came out of the civil rights movement came out of the Black church, which is why they were a target. Of course, Dr. King being a pastor of a church leading his group, the SCLC Southern Christian Leadership Conference, they promoted nonviolence. However, there was, of course, this tension, this struggle between nonviolence and self-defense. I think that people think that, you know, the likes of Malcolm X and others were promoting violence. They weren’t promoting violence. They were promoting self -defense. And the deacons for defense were a group of men who said, yeah, we’re going to defend our people as they are out. We’re not looking to be violent, but we’re not looking to be naive to say that we aren’t aware of what’s going on. A deacon in the church, a Christian church in this context, an African-American church, Black church, they are responsible for doing a number of things. And one of those things, they’re sort of like an elder in the way of, you know, ensuring that everything is okay with respect to operations in the church, but also with respect to safety in a church. And so those men took it upon themselves to arm themselves to make sure that when engaged in civil rights activity, members of the churches that come together were protected and were safe – whether they were marching, whether they were protesting due to, you know, of course, white supremacists that may have been around, KKK members that were around. And they came into conflict with Dr. King. There were a number of instances where they merged in terms of doing activism, but they came in conflict with Dr. King with respect to what their philosophy was versus his. And so again, that’s just another example of a story that we don’t talk about.

Civil rights has been hijacked with the philosophy of nonviolence. And I don’t see that as, you know, Dr. King hijacking. And I’m talking about sort of the apologist, the racist apologist who will say, well, you know, anything that wasn’t nonviolent is illegitimate. And that’s not the case at all. And so, you know, African-Americans, again, resistance, fighting back against any white oppression, is about resisting to the extent that if we have to defend ourselves in order to be free, that’s what we are going to do. And so the deacons of defense were just continuing in that mode of Black resistance.

Cyril: Why do you think we’re seeing such a backlash or what some have called a conservative whitelash to teaching history today and specifically the history of racism in the country, the history of the country continuing to struggle to overcome this, as well as black resistance?

Rann: I think that there’s a number of different reasons that we can say that, right? I think that oftentimes what is being told in the mainstream is that talking about this is making white people feel guilty. Talking about this is making white people feel like they did something wrong when it was not them that were there, but maybe ancestors of the sort. And there may be some truth to that, right? There may be some truth to that, but I don’t believe that that’s what it is. I believe that the powers that be when we look at the particularly the white power structure. The New York Times released an article a few years ago where it talked about 80% of the people in power in this country, whether it’s Congress or businesses or police and things of that nature, 80% of the people are white. So when I say white power structure, I’m specifically meaning those people in charge of the institutions and systems of our society. When you look at the history of the United States, when you look at Black history as it relates, when you learn, you have not the privilege of staying the same. You have to change because you learn information. If you don’t know how to cook and you’re taught how to cook, you’re never the same. Now you can go to the supermarket, buy food and cook as it relates to your person.

When you learn history, you can’t carry on in the same way. You have to make a change. And when we talk about Black history, when we talk about the history of white supremacy, racial capitalism, all of those things, it requires that people look at the world different in a way to say, how do we change the mechanisms of our society in order to not continue or perpetuate what’s been going on over history? The powers that be don’t want that. The powers that be don’t want people to be awakened to a

Ron DeSantis’s point, too woke, right? They don’t want that because if people are awakened to the realities of history, then it requires them to really do some introspection in a way to change. And that’s not going to be everybody. Some people are going to say, well, I like the way things are. I don’t like the way things can be if we change. And that’s the challenge for a lot of white people. I think that that is the fear that white people will have to wrestle with history in a way where they say to themselves, listen, am I going to continue to perpetuate what’s going on? Or am I looking to change the best ways that I know how? Those conversations will foment a number of people looking at the way that their politics are, looking at the way that they worship, looking at the way that they view the world, looking at the way that they recognize the economic structures of our society. Maybe they stop listening to mainstream news. Maybe they listen to international news now. Maybe they don’t fall for the Southern strategy. Maybe they’re in the words of Lyndon Johnson, they’re not allowing people to pick their pockets. There is a genuine fear of the power structure that if people are educated that they will no longer tolerate the BS of the power structure and that they will see the commonalities amongst people who don’t look like them, particularly Black people, in the ways that this system has harmed everybody. It harms everybody. It doesn’t just harm Black people. It harms white people. And W.E.B. Du Bois talked about the merging, if the merging of the white proletariat and the Black proletariat, you would have seen something change in this country. But because the power structure understood that, they kept folks separate. There’s a great skit on Saturday Night Live with Tom Hanks, it’s Black Jeopardy. And they bring Tom Hanks on and he has on this MAGA hat and they’re answering questions. And throughout the skit, they come to realize that this white guy with this MAGA hat has a lot in common with these Black people in terms of the way that they think. And it just goes to show that if you take working class folk, if you take poor folk on both sides, that can really make a change. That’s what got Fred Hampton shot and assassinated. He was working with the Young Patriots. Those folks had the stars and bars as their logo, working with the Black Panthers in Chicago, along with the Young Lords, the Puerto Rican organization. And that absolutely scares folks. So for me, it’s just a matter of trying to control narratives, but also trying to control the mindset of individuals to not coalesce to fight against the power structure that is harming us all using capitalism and using white supremacy to do so.

Cyril: I think that would actually make a great topic for another episode, kind of the history of and hopefully future of building a radical, multiracial, working class rainbow coalition to kind of liberate ourselves.

Just two more questions. First, what are you reading now these days? Any books on your shelf that you’re looking into that’s tackling history and Black history specifically?

Rann: Yeah. Yeah. I’m, I’m reading three books right now two new ones and an oldie but a goodie. The first book that I’m reading is a King by I believe is it Jonathan Eig, or I’m mispronouncing his name. Forgive me, but I’m reading his book, which is a really great book and retrospective of breath of just King’s life. It’s just really awesome just to learn about sort of the history of Dr. King in a fascinating, deep way. It’s a really good book. I’d say about 10 chapters in, which is really good. Yeah, love that book.

The second book is, I’m trying to think of it, oh, Black Folk, The Root of the Black Working Class by Blair Kelly. Really an awesome book. You know, thinking about the election of 2024 and even thinking about 2020 and 2016, you know, there was a lot of talk about the white working class and appealing to them, but not a real discussion or attention given to the Black working class. So, you know, that’s been a really fun book to read as well.

And the third book that I have just that I keep in my pocket is the Pedagogy of the Oppressed. I’m always reading through that and, you know, learning new things as I’m reading through. So those are the books that I have on on my shelf that I’m looking at right now.

I can tell you two that I finished. One would be Fear of a Black Republic. That’s by Leslie Alexander, really looking at the history of Haiti in a very different way. That book was really, really awesome. And the other book, it’s called White Philanthropy by Maribel Morey Carnegie Corporation’s an American Dilemma and the Making of a White World Order. It’s basically talking about the making of a new white order, world order, if you will, from that. So that book was just super insightful just on how white philanthropists utilize their resources in order to dictate narratives, particularly about people of color, but especially about Black people, and utilize that to do the kind of research that promotes a lot of these right-wing narratives that people actually believe. So those are just some really good pieces that I’ve got tackled over the last couple of months.

Cyril: Great, thanks. And let’s have a little fun with this last question as well. You’re organizing a symposium on Black history to help understand the present and think about ways to chart a more racially just future. Name three people living or from history who you would invite to participate and why.

Rann: Oh man, that’s so good. Three people in a symposium talking about the importance of learning Black history. So I think I would be remiss if I did not invite Carter Woodson, Dr. Carter G. Woodson, the father of Black history. You have to invite him. So, you know, creating Negro History Week, the Black History Month, the Association for the Study of Negro life and history. You got to invite him.

I think the second person that I’d like to invite, I think a journalist. And I’m thinking of Ida B. Wells Barnett, someone who was detailing the lynchings of African-Americans when no one else did someone whose coverage was so hard hitting that she was ran out of Memphis, Tennessee, and just did the work of a journalist reporting on this stuff. I think the historian, the journalist, I think that those two are absolutely integral.

And for my last person, man, I’d have to go Malcolm X, el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz I would have to go there. The man was self-taught in his history and understood what it was to be lied to about his history. And not only that, but most often people think of the time that he had with the nation of Islam, not thinking about his own conversion after that. I think that we lost so much when he was assassinated. To have him speak about that as well.

I think for me, yeah, those three, it would be Carter Woodson, Ida B. Wells Barnett, and Malcolm X.

Cyril: Well, thanks so much, Rann. I really want to encourage listeners, you know, if you want to celebrate Black history, not just Black History Month, but Black history, please go to your local bookstore and pick up a copy of Resistance Stories from Black History for Kids, which after reading it, I will tell you, is not just for kids. You will enjoy it yourself. You can read it with your kids if you’d like. But Rann, thanks again for coming on The Signal. I appreciate it.

Rann: Nah, thank you so much, it’s been a pleasure.