This story was originally published by Chalkbeat. Sign up for their newsletters at ckbe.at/newsletters.

I came to the United States 35 years after the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education of Topeka decision, ruling that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional.

As a mixed race student arriving from England with a strong accent and an Afro, I was not warmly received by my new suburban school community. I entered elementary school at age 7. The elementary school students immediately made fun of me for my British accent, and I was often called an immigrant and even a pilgrim.

By middle and high school, my peers made annoyingly frequent statements of their supposed colorblindness. “Abigail, I don’t see you as different from me,” they would say, “We are just the same.” Their statements, in which they claimed not to notice my Blackness, made me realize they were in denial about the racism that existed in our school community.

Now that I’m an educator, sometimes I look back at my experience and wonder, “What if I just had one Black teacher when I arrived?” I look back and know that pervasive racism in our school system is real and teacher repression — when educators are silenced and lessons challenged or banned — is real.

That is why Brown, which turns 70 this week, is often not taught to the fullness of its story and legacy. It is often taught as a celebration of American justice, equality, and exceptionalism. When I was in high school, the history teacher would smile at me during the lesson, proud of this history. I remember thinking, “Oh, so because of Brown, I should be grateful that I am the only Black student in the classroom right now? Because, mostly, I feel uncomfortable.”

To teach Brown fully, it needs to be done so through LaGarrett King’s principle of Black historical contention — the concept that not all Black people have the same ideas and approaches to Black liberation. But most of the time, we get one-dimensional lessons on the ruling because pan-African and Black nationalistic perspectives remain left out of corporate-produced textbooks and supplemental resources.

Despite the NAACP and its chief counsel Thurgood Marshall’s bold and unrelenting legal crusade against school segregation, and a victory in the nation’s highest court, not every Black person wanted their Black child to integrate into a white school.

READ: Bucks County Changemakers Interview with the NAACP’s Karen Downer

Many Black people had more than enough reason to not trust the public school system after Brown. As I have argued before, one of the strongest tools of white supremacy is denying Black people an education. Black families were rightly concerned about the racism their children would face post-Brown and the curriculums they would encounter. Rather than send their child to a white school, many just wanted their Black school to receive equal funding.

The No. 1 fault when teaching Brown is the assumption that society will make significant racial progress when Black students integrate into white schools. Historically, why has the starting point of the discourse been that Black academic success depends on a system that has racially targeted the Black community?

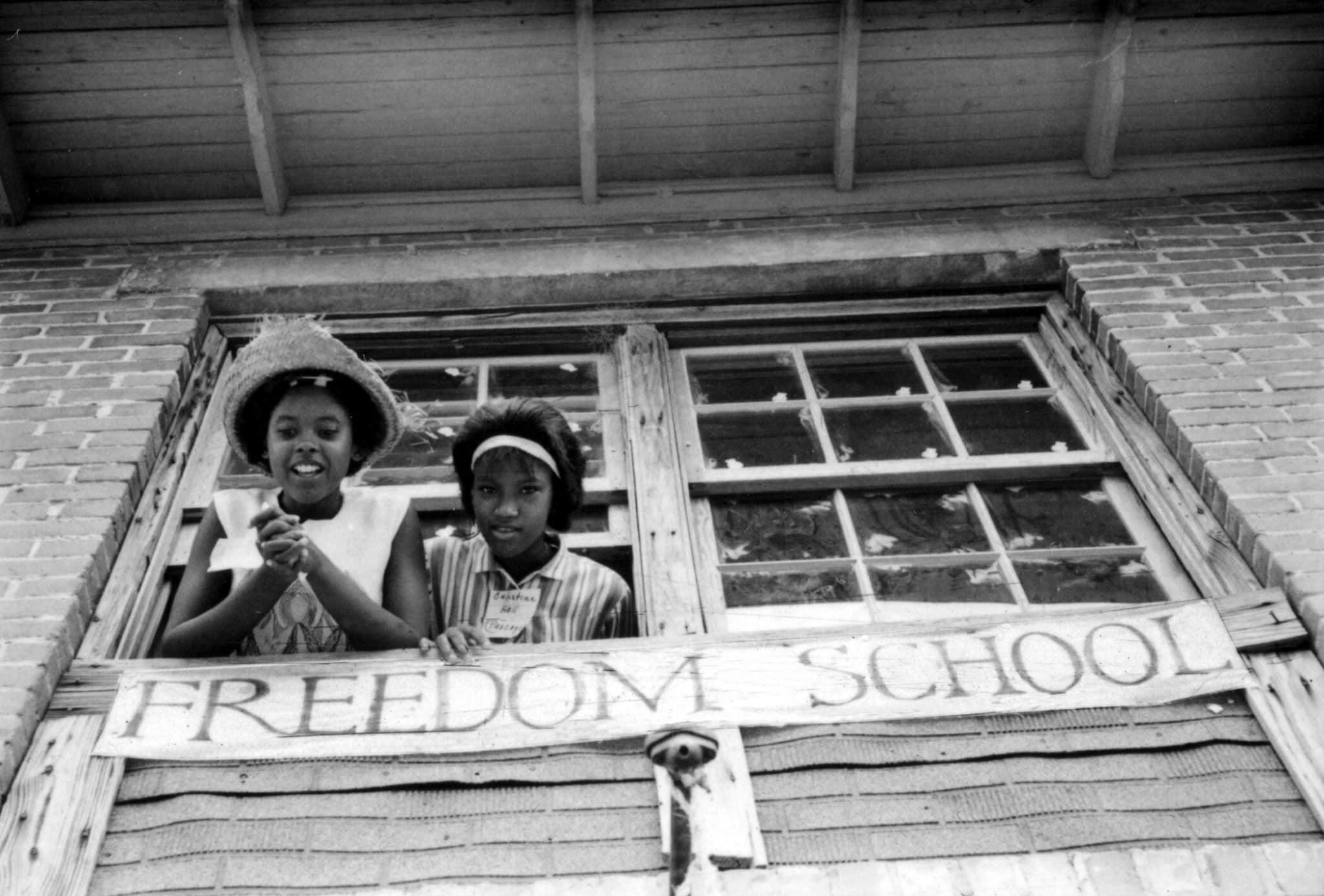

This is why the rise of Freedom Schools needs to be included in the conversation about Brown. Freedom Schools — free, alternative schools (mostly summer and after-school programs, but also day programs during school boycotts) — were created to prepare “disenfranchised African Americans to become active political actors.” Charles Cobb of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was among those who helped spearhead the Freedom Schools movement.

Freedom Schools in the 1960s were inspired by the centuries-old pan-African approach to education, with its Afrocentric perspective and focus on self-determination. Lessons at these schools, located in the South and around the country, focused on literacy and activism. They were also infused with Black history and rituals such as “libations,” or offerings to ancestors. Some such rituals are still common practice at Freedom Schools that exist to this day.

Philadelphia Freedom Schools, built for Black children, tackle literacy and love.

It was not until I worked at the Center for Black Educator Development’s Freedom School Literacy Academy that I discovered, while teaching Russell Rickford’s “We Are an African People” that post-Brown there were three dueling types of Freedom Schools: those established by the Nation of Islam, the 1960′s Freedom Schools, and the Black Panther Party’s Freedom Schools. The Black historical contention and nuances between these schools and the Black nationalists who founded and fostered them are as important as the movement to overturn legal school segregation.

READ: Being ‘Woke’ to Racial Injustices in The United States Has a Long History

I just finished reading Dennis Lehane’s “Small Mercies,” and was unaware of the extent to which some white parents in South Boston did everything they could to avoid school integration. After reading more about integration efforts in South Boston this image of a Black student, Valerie Banks, resonated with me when I reflect back to my first days as a student in a suburban Pennsylvania school. Valerie Banks was the only student to show up to class at South Boston High School on the first day of court-ordered busing. I ask myself, “On the first day the white students return, to what extent would her experience be like mine?”

When I teach Brown to my ninth grade African American History and my AP African American Studies classes, I go over the differences between de facto and de jure segregation — that is, the difference between segregation that occurs by choice/reality and legal segregation. I ask them which one has the bigger impact on society and then point out that for many in the pan-African movement, there is no actual distinction. The white flight that followed Brown offers further evidence of why this perspective needs to be included in classrooms.

Learning about Black nationalism provides students the opportunity to engage with alternative strategies aimed at achieving Black freedom and self-determination. For this reason, I include lessons from some of the first Black nationalists such as Paul Cuffee and Martin R. Delany. (Some more of my favorite resources for teaching about Brown and its aftermath can be found here and here.)

As the educator and writer Rann Miller argues, “For too long, Black students have had the burden of adjusting to a racist society.” To make amends, teaching the whole story of Brown is a step towards helping the Black community heal.

Chalkbeat is a nonprofit news organization covering public education.