This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

As the remnants of Hurricane Ida barreled north in September 2021, Chris Erdner heard a startling warning on TV: Residents in her area needed to seek shelter immediately. Erdner’s quiet suburban neighborhood in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, was directly in the path of a tornado.

Erdner and her husband rushed to the basement. “I don’t know if you’ve ever heard it,” she said, of the “incredible noise” generated when a tornado passes overhead. “It sounds like a freight train.” Although the tornado only lasted a short time, it felt much longer. Listening to the storm raging outside, Erdner wondered if the heavy steel doors leading from the yard to the basement would be ripped off.

“It shocked us,” said Erdner, who grew up in eastern Pennsylvania and has lived in the same house in Upper Dublin Township for more than 30 years. “One of the things we always liked about living in this area of Pennsylvania is that we didn’t usually have to worry about things like tornadoes and hurricanes.”

Since that frightening day in 2021, Erdner has noticed more tornado watches and warnings issued for her area, and she worries what this might mean for the future. “Because if this is some sort of effect from climate change,” she said, “this is not going to get better, this is going to get worse, right?”

According to National Weather Service data, 37 tornado warnings have been issued in Erdner’s area since 1986, and 27 of them occurred after 2010. Data on tornadoes in Pennsylvania dating back to the 1950s seems to show a slight increase, with the most active years all after 1980.

Erdner’s concerns about climate change, trends and risk were echoed by residents in western Pennsylvania in June, when six tornadoes hit the state within an hour. Two tornadoes rated EF2, the same rating as the 2021 tornado, with estimated wind speeds between 111 and 135 miles per hour, were also recorded in May, and there have been 22 tornadoes in Pennsylvania so far this year. With 1,495 tornadoes occurring across the United States from January through July, this year’s preliminary count is second only to 2011 and well above average for the first seven months of a year. In places not typically associated with tornadoes, like West Virginia, Alabama and New York, longtime residents are asking similar questions to Erdner’s.

Scientists who study tornadoes say the answers to those questions are evolving and complex. “We can definitely say that over the last 30 years in the Northeast, we have seen more tornadoes, and there have been more favorable environments for tornadoes. Both of those things are true,” said Victor Gensini, a scientist at Northern Illinois University who researches tornadoes and climate.

“We cannot definitively say that we know what’s causing it,” he said. “We believe it’s incredibly, extremely consistent with our projections of a warming climate, but there’s still a lot more work to do.”

Tornadoes are rare, especially in the Northeast, but they can happen anywhere if the circumstances are right. They have been documented in every U.S. state. Since 2004, tornadoes have caused roughly $90 million in property damage in Pennsylvania alone.

“Because if this is some sort of effect from climate change, this is not going to get better, this is going to get worse, right?”

Paul Markowski, a meteorologist at Pennsylvania State University, first became interested in the science of weather as a kid in 1985, watching news coverage as a series of tornadoes hit Pennsylvania, killing 64 people and setting records for the deadliest tornado in state history.

“The laws of physics that govern atmospheric motions are agnostic about county, state and country,” he said. “If you get Oklahoma conditions in Pennsylvania, you’ll get an Oklahoma event.”

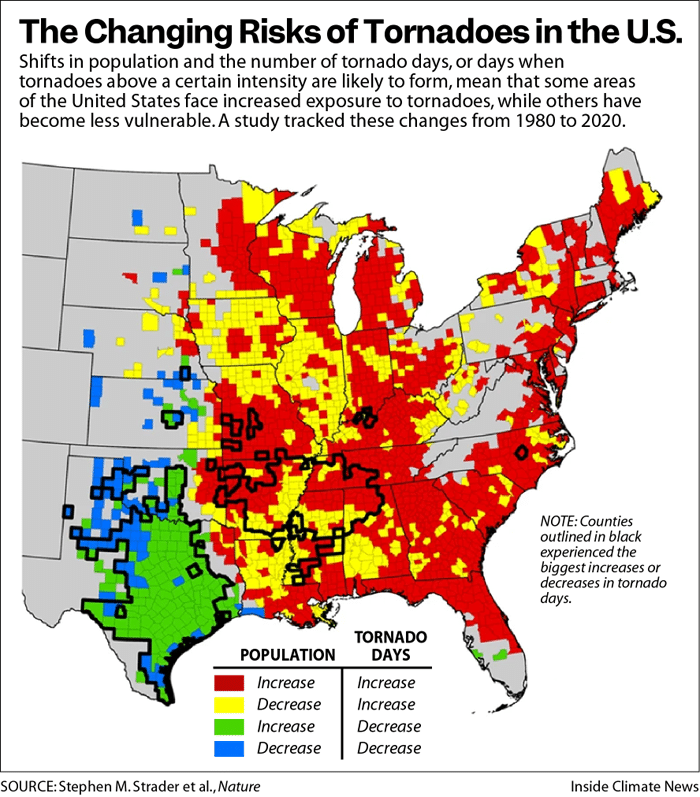

New research suggests that tornadic activity may be shifting east and north, away from Tornado Alley, which traditionally runs through Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma and Texas. A 2018 study Gensini co-authored found there was an upward trend in tornado frequency across parts of the Northeast, the Southeast and the Midwest, and a decrease in tornadoes in some parts of Texas, Oklahoma and Colorado. Activity is becoming more concentrated, with more tornadoes occurring on fewer days, and there are also changes in the seasonality of tornadoes: less frequent in the spring and summer and more frequent in the fall and winter.

Pinpointing what might be causing these changes, and how much of a change is actually happening for any given metric, is extremely complicated. Harold Brooks, a senior scientist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory, said the effects of climate change are like a chain with many links. Rising temperatures, for example, are an early and direct link on the chain. Increasing rainfall is another. But the formation of tornadoes isn’t impacted by climate change in straightforward ways.

As the planet warms, “some of the variables we expect will become more favorable [for tornadoes]. Some will become less favorable,” Brooks said. “We don’t even know exactly how many links there are on the chain, let alone what the chain is.”

Gensini hopes that in the future, it will be possible to connect tornadic activity to climate change with a rapid attribution system similar to modeling that scientists currently use to analyze heat waves, but more research is needed to reach that point.

One of the obstacles to analyzing tornadoes’ long-term behavior is their relative rarity. Because they are unusual, datasets concerning their appearance are small. Consistent records for tornadoes in the U.S. only go back to the 1950s, making the record even smaller.

“That’s a very short record compared to other climate records we have. There are no proxy data for tornadoes, and because of that, it’s hard to establish trends. There’s a lot of year-to-year variability in tornadoes, and that’s essentially noise that is masking any trend,” Markowski said. “I’m not saying there aren’t trends there. It’s just harder to see them.”

Markowski does not think there is enough historical information about tornadoes to say with certainty that they are becoming more frequent in the U.S. as a whole or in Pennsylvania, but he said there is convincing evidence that tornadic activity is moving east and north.

Tornado data in the United States is also compromised by lack of consistency in everything from tornadoes’ intensity (which is based on after-the-fact damage assessments) to the National Weather Service alerts that residents get on their phones and TVs about storms.

“Humans are issuing those watches and warnings and have their own biases. I can sometimes tell who’s working a particular shift by looking at what product is getting issued,” Markowski said.

Increases in population and residential development and the availability of phones that can also shoot video, as well as growing interest in storm chasing, all play a role in the documentation of tornadoes, too. That’s had a corresponding—and confounding—effect on the record.

“Thirty years ago, if a tornado happened in a farm field in Kansas, unless it hit the farmer’s house, it’s probably not in the database,” Gensini said. “Today, if you have the weakest of all weak tornadoes in that same field in Kansas, I can promise you at least 10 storm chasers are on it, and that video is up on YouTube within 10 minutes.” The success of this summer’s blockbuster “Twisters” is evidence that the public’s fascination with tornadoes isn’t likely to die down anytime soon.

“The laws of physics that govern atmospheric motions are agnostic about county, state and country.”

Brooks said meteorologists who study tornadoes and extreme weather often have stories about storms they witnessed firsthand that do not match the information that ended up in the official record. “There’s an F2 tornado in the database in June of 1987 in East Central Illinois,” he said, “and I was three miles from the tornado, and I can guarantee you there was no F2 tornado there.”

In part because of these anecdotal experiences, meteorologists wonder how much trust can or should be placed in the historical record. “Even when we see the trends we can measure based on the data, there’s still uncertainty,” Brooks said.

What these uncertainties about cause, effect and trend lines mean for the average person is a separate question. Scientists say increases in tornadic activity outside the confines of Tornado Alley are small and may not be meaningful when trying to assess risk on an individual level. On a larger scale, however, they have huge implications.

“The increases we’re talking about are like one tornado in a county per decade,” Gensini said. “That sounds like really, really small increases, but when you start aggregating over the entire state, it’s actually a really, really big deal.”

Even a tiny increase in the number of tornadoes in the Northeast and mid-South could correspond to a much greater potential for damage and loss of life because those regions have higher population densities compared to the Great Plains. In the South, more poverty and the prevalence of mobile homes mean that more residents are vulnerable to the effects of extreme weather.

It’s important to understand that what makes an extreme weather event a “disaster” is not the event itself but the number of people and buildings in its path, Gensini said. “No disasters are natural. I hate that term. Disasters are man-made constructs, because the disaster wouldn’t happen if humans weren’t there.”

“Studying the climate and studying the changes in the climate is incredibly important. We definitely need to know if tornadoes are going to get stronger or more frequent in certain geographies,” he said. “But the reality is, we know for certain that there are going to be more tornado disasters in the future, and it has nothing to do with climate and everything to do with the fact that the human-built environment is continuing to grow.”

For organizations concerned with collective risk, like government agencies and insurance companies, these changes matter. “As an individual, 10 percent really shouldn’t change your risk perception very much, because tornadoes are still relatively rare events,” Brooks said. “But it may matter a lot to people like a statewide emergency manager, right?”

In 2023, Pennsylvania’s Emergency Management Agency ranked tornadoes as a “medium risk,” alongside threats like drought, wildfires and landslides. Compared to 2018, nine more counties ranked tornadoes and wind storms as a high risk. The agency determined that more than 4 million people live in areas vulnerable to tornadoes in Pennsylvania, and the value of exposed buildings tops $1 trillion. In a statement, PEMA’s director, Randy Padfield, said threats from tornadoes “are always evolving.”

“PEMA wants the public to be aware of the risks that tornadoes pose, ensure they have a way to receive weather alerts and take appropriate actions to protect themselves and their family members should a tornado impact their area,” he said.

A tornado watch means that conditions are favorable for a tornado to form, while a warning means that one has been sighted or detected by radar. Markowski said if you’re issued a tornado watch, you should pay attention to your surroundings and be ready to act in case a warning is issued. Warnings are more serious and can contain directions to take cover immediately, preferably in a storm shelter or basement.

Markowski advocated for “more surgical” and precise tornado warnings. “There is harm in overreacting,” he said. “The ‘crying wolf’ effect is real.” For people unused to tornado alerts, receiving a warning that turns out to be a false alarm could be deadly in the future. “If you’re in sunshine and your phone is buzzing telling you to go to the basement and you didn’t even perceive a threat, I guarantee you, if you’re human, you will respond differently the next time.”

In Oklahoma, in the heart of Tornado Alley, Markowski said, the general public is far more weather-savvy than elsewhere in the country.“They have to be, because not being aware can get you killed there,” he said.

Oklahomans’ expertise is evidence that “it is possible to teach people and elevate their understanding” about tornadoes and storms, regardless of their background or level of education, he said. Knowing how to interpret and respond to weather alerts saves lives in Oklahoma and may become more important elsewhere as changes in tornadic activity expose different parts of the country.

When Erdner went outside after the storm had passed her Pennsylvania neighborhood, everything had changed. The front yard was littered with hunks of roofing from a nearby construction site, nails exposed; drain pipes and gutters; chimney caps and shards of glass. Upended telephone poles and mature trees lay horizontally on the ground, wires and roots crisscrossing the road. A neighbor’s trampoline was carried by the wind into Erdner’s garden shed and then down the block. “We walked up and down the street, as did all of our neighbors, just checking on each other to make sure everyone was OK,” she said.

Their house sustained $10,000 in property damage, including to fencing, a screened-in porch and siding, and they spent $5,000 to clear fallen trees from the yard. The house was without electricity for six days. Despite all of this destruction, Erdner considers herself lucky.

“It’s strange, what tornadoes do,” she said. “Some of our neighbors did not fare as well as we did.”

The tornado tore the second floor off two of her neighbors’ houses. Half a mile away, in Fort Washington, a woman was killed when a tree fell onto her house.

Three years later, Erdner’s neighborhood is still not the same as it was before the tornado, and neither is she. She pays far more attention to weather forecasts for storms now and reaches out to friends who live close by to make sure they’ve seen and acted on alerts.

“It was really traumatizing. You don’t really realize it until there’s another warning or watch, and then you feel it,” she said. “Physiologically, it all comes back.”