Renée DiResta’s exceptional Invisible Rulers: The People Who Turn Lies into Reality examines the intricate architecture of online communication and its consequences.

The author sets out her purpose early: “This is not a book about social media. There are enough of those. Rather, my focus is on a profound transformation in the dynamics of power and influence, which have fundamentally shifted, and on how we, the citizens, can come to grips with a force that is altering our politics, our society, and our very relationship to reality.” (11)

It is an complex, multi-layered story dominated by the trinity of “influencer-algorithm-crowd.” (113) The term “influencer” covers a broad array of people that includes, according to the author, Entertainers, Explainers, Idols, Gurus, Generals, Reflexive Contrarians, and Propagandists. Influencers are relevant because they find topics that resonate with an audience and, perhaps more importantly, they are relatable to the people who consume their product. (51) They can simultaneously be leaders and members of the crowd.

The “crowd,” or audience, has its own unique attributes. DiResta makes the point that online crowds are “no longer fleeting and local but persistent and global.” (67) They can be positive in nature, comprised of communities offering individual support or collective action for reform. Unfortunately, the pendulum often swings the other way as well. The crowd can embody the worst qualities of humanity that find sustenance and traction online. As the author notes, “At its worst, Twitter made mobs—and Facebook grew cults.” (71)

The angry, destructive online crowd has seemingly contradictory traits. Members enjoy anonymity and strength in numbers, while they portray individual David versus Goliath struggles against omnipotent global power. Billionaires form alliances with ordinary folks, each expressing their own portions of grievance. (237) In the prevailing “Age of Rage,” negativity resonates and incites. (275) What explains this? “The influencers get engagement and its spoils: more clout more money. The troops get the camaraderie of a fight and a sense of mission.” (280) The hero’s journey is a tempting incentive.

Presiding over both are the algorithms, which can boost a particular message or limit it regardless of quality or truthfulness. And, as DiResta points out, software does not stand still. With the advent of AI, technology is becoming a direct participant not just in shaping access to the message, but actively creating it. The “generative pretrained transformer” (GPT) can reproduce “the style and tone of any given community down to the in-group language and slang.” (204) In effect, AI is an interesting and disturbing addition to our contemporary “democratized” media landscape.

To explain the relationship between these three sets of actors, DiResta uses the term “murmuration,” the “undulating dance” conducted by groups of birds as they react to individual changes of course. (111) It is a beautifully lyrical way to understand how algorithms using “collaborative filtering” features to resonate with online users. (59) Adept influencers “curate” information and amplify it in ways that can be both intuitive and calculated around things like “engagement metrics.” (23, 87) The process is technologically complex and organic at the same time.

Explaining all of the features of this undulating dance is something beyond the scope of this review. But, if I were to focus on one common thread that repeatedly appears in Invisible Rulers, it would be relatability. It is the core quality of the most successful influencers. Joe Rogan is an excellent example. His online/podcast persona, the principles of which Naomi Klein unpeels in her superlative book Doppelganger, is relaxed and relatable. He is a regular lunkhead, expert at nothing and “just asking questions.”

Relatability is constantly malleable and evolving. It might invoke the most basic features of confirmation bias, when proponent, audience, and the algorithmic middleman simply agree. However, a self-reinforcing cycle of agreement depends on the nature of the “influencer-algorithm-crowd” trinity. If Joe Rogan is weak tea, Tucker Carlson, Alex Jones, Steven Crowder, Charlie Kirk, Candace Owens or any other regular “shit poster” will up the ante from “friendly and engaging” (233) to “performative aggrievement.” (177) The possibilities are endless.

Traditional thinking based upon “consensus realities” struggles mightily against this onslaught. (41) Public officials, scientists, educators, and their like, live within the blinders of their professional standards. Peer review is not built for entertainment. Careful discourse is next to impossible within the format and tempo of social media. As DiResta notes at the beginning of the book, many experts dismiss the tumult occurring on the worldwide web. “It was, after all, just some people online. It wasn’t real life.” (9)

A perfectly normal response, but a serious mistake. Many experts initially fail to understand the costs and consequences of dealing with a “factionalized public.” (224) Mistakes made during the normal course of research and experimentation can be seized upon, as they were during COVID, as points to “curate” against authority and expertise.

READ: New Book Examines How the QAnon Conspiracy Radicalized Its Followers and Unhinged America

This process of “delegitimization” has enormous consequences. (150) In a rational universe, COVID-19 should have been a reality check. But it wasn’t. As the author notes: “The constantly mutating coronavirus was a completely indifferent pathogen that could kill people whether they believed in it or not—and in early 2020, many were dying. Yet some prominent influencers—and even world leaders—within highly conspiratorial bespoke realities insisted it was not dangerous, even as media covered refrigerated morgue trucks.” (227)

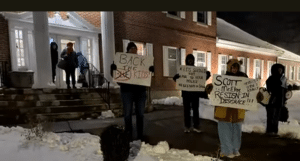

There are ongoing costs to the responsible actors in this story. Public officials — Anthony Fauci is a good example — from the top tiers of the federal government to local school boards have been the victims of doxing, swatting, and death threats. Many have quit. Others choose silence to avoid scrutiny. This dangerous not only to civil servants who do their jobs in good faith every day, but also to our democratic discourse in general. (289)

How do we reverse this dangerous course and rebuild a “new civics”? (12) DiResta considers a variety of solutions. One is online content moderation, which may affect how information is curated and boosted by both software and influencers. (316) Reform along these lines impacts both the quality of content, through factchecking, and its “reach” (access to audience). Major platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have attempted content moderation only to be met with howls of “censorship.” Some have modified their policies or, after Elon Musk transformed Twitter to X, abandoned many of them. In practice, content moderation will not stop migration to lesser regulated platforms like Gettr, Truth Social, Gab, or Telegram. (209) Regardless, the author still argues that moderation built around established, international standards, informed by empirical evidence, and transparent to users may still be effective (320)

Government regulation of online content, a modified form of long standing “fairness doctrine,” may offer some important contributions. DiResta specifically addresses commercial speech and paid political speech, particularly the ongoing practice of “political ads masquerading as organic content on Tik Tok.” (106, 323)

Interestingly, DiResta argues that the most effective reform might be: “Putting humans back in the loop.” (334) Allowances for public scrutiny of internet content, “crowd-sourced fact-checks,” may create “friction” that slows and deconstructs information before it can become viral. There are a number of current platforms like Mastodon and Bluesky that already follow some of these practices.

READ: Understanding Why Christians Are Seduced by QAnon and Conspiracy Theories

We might find some future equilibrium between advancing technology and human self-awareness. (341) Society adapted to the printing press, radio, and television. The internet will not be an exception. Education will be key to this process, but it has to be motivated by a willingness to take intellectual risks and defy the inborne prejudices. The human solution to what ails us online might be our greatest hope, but it is also limited by the very nature of humanity.

Time will tell.

And during that time, we might have to rediscover patience, tolerance, and other qualities so badly atrophied by our electronic indulgences.