Despite all the talk of “Christian nationalism” today, most Americans never have heard of it, according to Greg Smith, senior associate director of research at Pew Research Center. And that makes measuring public opinion on the topic difficult, he told a group of journalists and religious leaders Sept. 10.

Smith was part of a panel discussion on Christian nationalism at a symposium held at Fordham University to celebrate the 90th anniversary of Religion News Service.

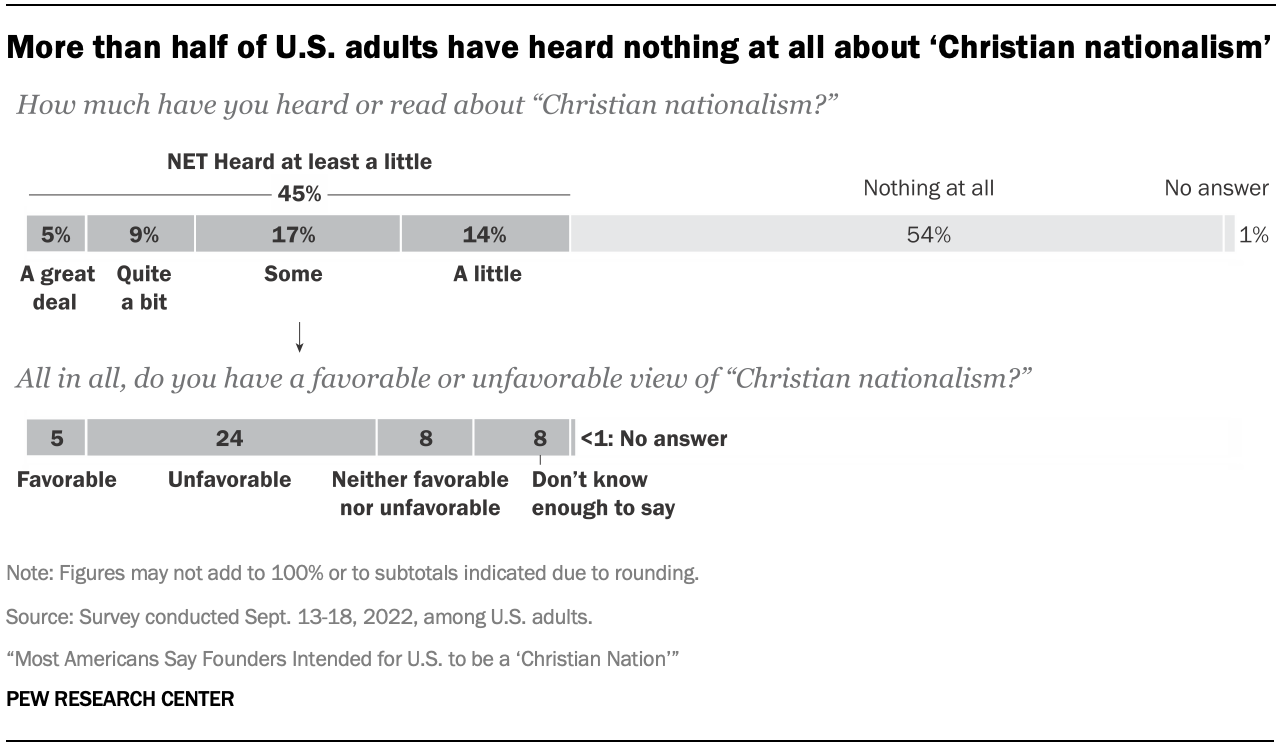

“More than half of Americans tell us they’ve heard little or nothing about Christian nationalism,” Smith said, referring to Pew polling conducted in July 2022. “Furthermore, even among those people who tell us they have heard of it, many of them tell us they don’t know enough about it to express an opinion of it one way or the other.”

Therefore, to measure public opinion on Christian nationalism requires indirect questioning, he explained. That mirrored a similar presentation made at the symposium by Robert Jones and Melissa Deckman of Public Religion Research Institute.

Like PRRI, Pew Research measures attitudes on Christian nationalism by asking a series of questions about ideas at the heart of Christian nationalism, Smith explained. “Maybe most broadly, we’ve asked people straight up, ‘Do you think that the United States should be a Christian nation?’ And when you ask that question, a lot of people, 45% of Americans, say, ‘Yes, I do think the U.S. should be a Christian nation.

“But then you’ve got to follow up and ask people, ‘Well, what do you mean by that?’ And it turns out that many people, most people who say they think the U.S. should be a Christian nation, what they mean is that U.S. society should be informed by basic Christian values.”

That is different than wanting a theocracy, he said. “Most people who say they think the U.S. should be a Christian nation do not go on to say that what they mean is they want a theocracy.”

That leads to a set of narrower questions Pew, a nonpartisan entity, asks to gain more insight.

“We’ve tried asking people much more pointed questions like, ‘Do you think we should stop enforcing the separation of church and state?’ Or, ‘Do you think the federal government should declare Christianity to be the official religion of the United States?’ And when you ask these more pointed questions, you get much lower numbers expressing agreement with these ideas.

“Just 16% say they think the U.S. should stop enforcing separation of church and state. Thirteen percent say they think the federal government should declare Christianity the nation’s official religion. And then most interestingly, if you put these two questions together, you find only 4% of U.S. adults express both of these points of view.”

Yet Christian nationalism is known to be a broader idea than that, Smith admitted. So while one of these polling approaches is too broad, the other is too narrow.

READ: These Evangelicals Are Voting Their Values — By Backing Kamala Harris

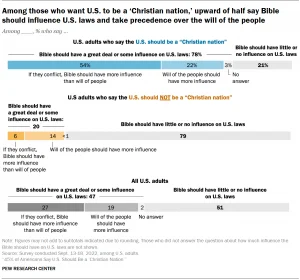

“Really what we need is a more middle ground kind of approach. And one of my favorite sets of questions for getting at this topic asks people about how much influence they think the Bible should have on U.S. laws.”

In Pew polling, respondents are asked how much influence they think the Bible should have on U.S. laws. “And when you ask that question, about half the public says they think the Bible should have either a great deal or at least some influence on U.S. laws,” Smith said.

But that’s still not enough data.

“Then we follow up and we ask people who say they want the Bible to have influence on U.S. laws, ‘Well, what happens if the Bible and the will of the people conflict with each other? What then, which one should have more priority?’

“And when you ask that question, what you find is that about a quarter of the public, 28% of all Americans, say they think the Bible should influence U.S. laws. And furthermore, if it conflicts with the will of the people, we should place more importance on the Bible over the will of the people.”

Holding such a view is about more than holding a high view of the Bible, Smith commented. “They’re saying explicitly it should play a role in lawmaking, and they’re doing more than simply saying that the Bible should play this role because most people want it to. They’re saying that even when it conflicts with the will of the majority of the people, we should place more weight on the Bible.”

Who in America today holds such views?

It’s not just white evangelical Protestants, he said. “That’s also a commonly held view of many Hispanic Protestants. Half of Black Protestants say they have this view of the Bible and lawmaking. Smaller numbers, but still significant numbers, of white Protestants who aren’t evangelical and large numbers of Catholics, about a quarter of Catholics, say the same.”

The bottom line, he said, is that assessing beliefs about Christian nationalism is harder than it looks and the ideology’s adherents are more diverse than most religion scholars imagine: “It’s critical when you’re thinking about Christian nationalists, when you’re reading about Christian nationalists, to really look closely at what does this mean in this particular case.”

And don’t look only “in the places you might expect,” he added. “We consistently find that significant numbers across a variety of Christian traditions and across a variety of social and demographic groups express support for some of these ideas, depending on how you ask about them.”

This article was originally published at Baptist News Global, a reader-supported, independent news organization providing original and curated news, opinion and analysis about matters of faith. You can sign up for their newsletter here. Republished with permission.