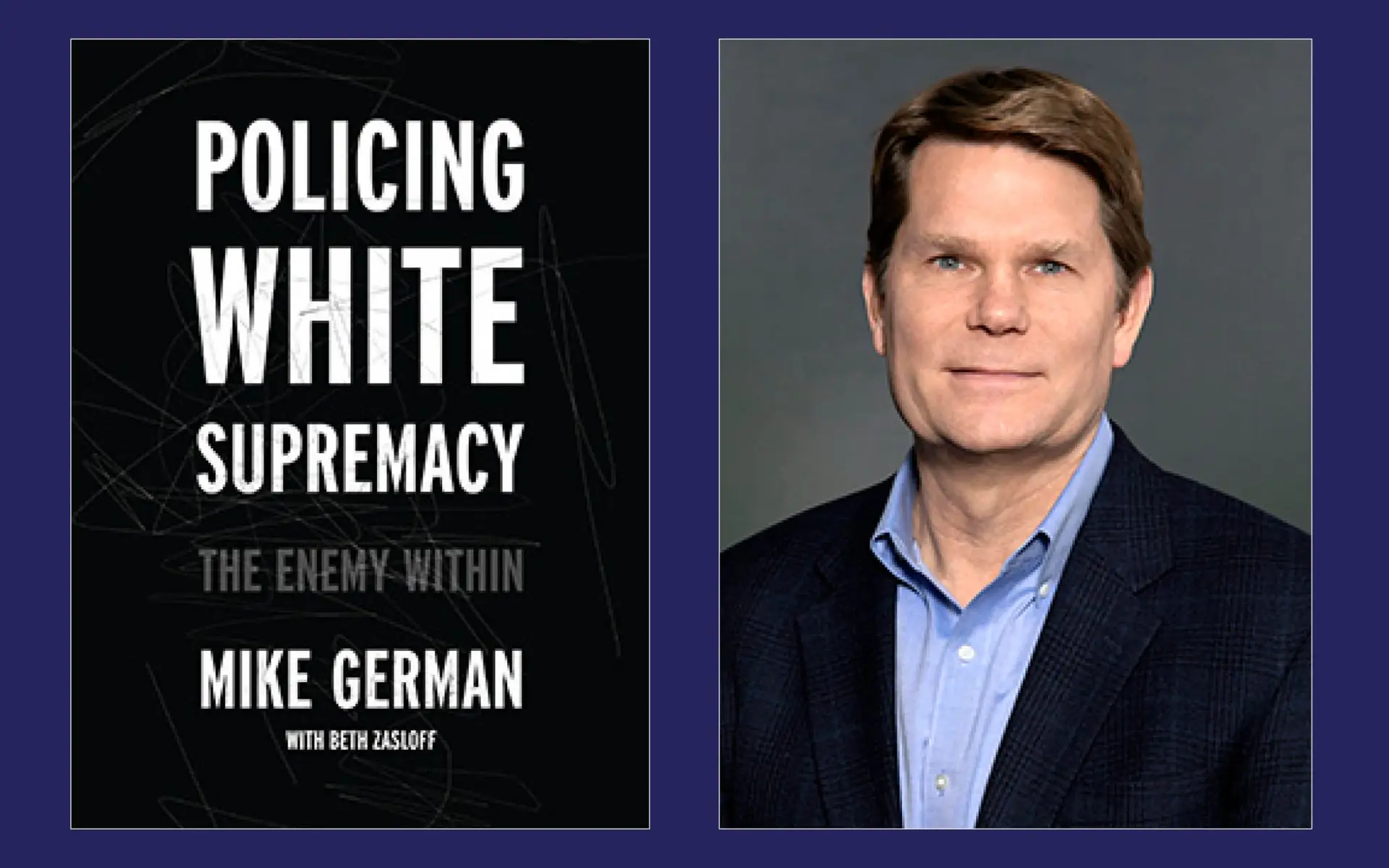

Mike German is a fellow with the Liberty and National Security program at the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law School. He has worked at the ACLU and served sixteen years as an FBI special agent, 12 of which he was tasked with combating domestic terrorism, sometimes going undercover and infiltrating white supremacist groups and militias. He is the author of Thinking Like a Terrorist as well as Disrupt, Discredit, and Divide: How the New FBI Damages Our Democracy. Today Mike joins us to talk about his new book Policing White Supremacy: The Enemy Within, which comes out Jan. 7. In it he urges law enforcement to prioritize policing far-right violence (which has been lax) and end tolerance for racism and right-wing extremism within its own ranks.

(Also listen on Apple, Spotify, Google, Podbean, and iheart)

Before we start discussing your new book, Policing White Supremacy: The Enemy Within, can you talk a little bit about your career with the FBI, specifically the type of work that you did during the 12 years you were tasked with combating domestic terrorism?

Sure. I joined the FBI in 1988 straight out of law school and immediately was assigned to investigate savings and loan failures, which back then were the type of elite fraud du jour and was looking for something different, something a little more interesting and an agent who was a friend of mine said, well, I’ve started this case involving neo-Nazi skinheads here in Los Angeles and you’re young and blonde, and could fit right in with those groups. So I spent the next 14 months working undercover targeting neo-Nazi skinheads in Los Angeles that were preparing for a race war in the aftermath of the civil unrest following the police beating of Rodney King. I finished that case. A number of people went to jail, mostly for weapons trafficking and plotting several attacks, a couple of bombings that occurred that we solved. And then about a year later, the Oklahoma City bombing happened and all of a sudden it was very interesting and it was very interesting to watch it from both the perspective of law enforcement and understanding the perspective of the groups. But it was interesting how law enforcement and the media characterized Tim McVeigh as a member of the far right militia groups, what we then called anti-government militia groups, rather than highlighting his connections to white supremacist groups, of which there were several. And even now, people sometimes I talk to are surprised that he was also involved with white supremacist groups. kind of because of the attack, many of the groups started characterizing themselves as militia to try to gain some of that notoriety based on the Oklahoma City bombing and an agent called me from the Seattle division saying that they had a militia group up there in Washington and asked me to go undercover again. And it was very similar conduct that they were involved in weapons manufacturing, illegal weapons manufacturing and trafficking, and plotting bomb plots, manufacturing explosive devices. And I spent the next eight months with that group. I had learned to correct some of the mistakes that I had made, but interestingly, after both cases, I continued to do all kinds of undercover work and assist other agents working domestic terrorism cases. But I asked the domestic terrorism unit at FBI headquarters if they were going to debrief me, you know, the 14 months spent undercover with neo-Nazi skinheads was, was quite an education. You can imagine for a kid just a few years out of law school. And I learned quite a bit about how the movement operates that kind of counters common wisdom about these groups. We tend to think of them as what the government calls extremists, violent extremists that are on the edge of our society. But what I learned is they’re far more tied into our society than we often want to acknowledge. And understanding that and understanding what their true goals are I think is what would help law enforcement better understand the nature of the violence.

How did this experience change you or just change the way you thought about the country or your worldview?

Well, it was fascinating because I definitely got an education in the history of the United States of America that I didn’t get growing up and even progressing through a college education and a law school education, understanding that these groups aren’t motivated by some extremely weird, strange belief out there, or at least not the main body of them. This is a broad movement and there are a lot of strange ideas within it. But for the most part, they were instructing me and teaching me. It was an extremely literate movement. They would give me books, they would give me pamphlets, they would put me on the address list of newsletters so I would get what they were writing and a lot of it harkened back to theologies, some of it was religious philosophies that justified slavery back in the day, that justified European colonization of indigenous lands. These activities were supported by a foundation of theology and philosophy that justified these what we now recognize as horrendous activities. And the way they looked at history, you the civil rights movement really only gave us de jure equality in law in the 1960s, right? So what they look at is hundreds of years of history before that and suggest that this experiment with the multicultural pluralistic nation protected by the rule of law is an aberration that needs to be changed back. And understanding how those theologies and philosophies continue to affect current government policies and being able to see that more clearly because I understood that history. And you can see it in our immigration laws. You can see it certainly in our criminal justice system. And as I became more interested in learning more about it, and particularly as I became an advocate at the ACLU and here at the Brennan Center now, I think is one of the most misunderstood parts of how we look at a nation at racist and white supremacist far-right militant crime. You know, we tend to look at it just like the crime you see from other extremist groups rather than recognizing that it is often in the form of state violence has to be understood that way in order to address what are some of the more serious implications of it.

So you’re doing this really important work for the FBI, infiltrating and unmasking these white supremacists and militant movements and actors. But then in 2004, you decided to step away. What happened?

So having spent a lot of time working in counterterrorism, particularly on the domestic terrorism side, I was probably one of the least surprised to find on September 11th, 2001, that our counterterrorism division was in disarray and, international terrorism was, was worked on a different, management structure than domestic terrorism, but some of the similar problems existed. Recognizing that while seeing that the reforms that the FBI was demanding, expanding surveillance, targeting entire communities as suspect communities, that those policies would be ineffective. I also realized that my job as an FBI agent was just to do the best I could on my cases. And I was approached to do an undercover operation that involved this case that didn’t go to trial so I can be less detailed about it, but basically involved support or US supporter of a Middle Eastern terrorist group reaching out to a local white supremacist group seeking their assistance in the post 9-11 environment targeting Muslims, basically going in with the pitch that you hate Jews, we hate Jews, we’re trying to harm Jews in the Middle East, you should support us, we’ll work out our other problems later, but this is an opportunity to support us. So it was a fascinating opportunity to get into both sides of these groups, right? Both the understanding how the U.S., how Americans supporting these foreign groups operate, but also how the white supremacists might assist them. But unfortunately, because as I suggested, the FBI’s reforms were not really designed to address the problem, which was the mismanagement of intelligence, not the lack of intelligence, but the mismanagement of it. And because they opened the aperture, for collection without fixing the management structure, the same kind of problems were occurring and the case was being mismanaged. And ultimately I learned that an informant the FBI had employed had made an illegal recording and ust hadn’t been properly instructed and made a bad decision not understanding how the law worked. And rather than addressing that situation they told me they were going to pretend it didn’t happen. And while I was pretty good at pretending when I was undercover, I wasn’t willing to pretend when I was on the witness stand as an FBI agent. So I raised the concern. And this was at a time when President George Bush and FBI Director Robert Mueller were still being criticized for the FBI’s failures leading up to 9-11, and they had asked for any FBI agent out there who knows of a counterterrorism investigation that has gone awry to report that. So I did, and what I learned very quickly is they didn’t really want it reported. And I received significant repercussions from management, told I was never going to work undercover again, and tried to continue using the what the FBI and the Justice Department called the appropriate channels to report this misconduct. But what I found was that that whistleblower system was really a trap. It was designed to identify you and to identify you and marginalize you as the problem. And there were retaliatory investigations and other just retribution that after two years of that and realizing this was never going to get anywhere, I decided that I would resign and go public with the issues, went to Congress, and they started an investigation. The Inspector General started an investigation and ultimately left the FBI and went and started working at the ACLU’s National Policy Office.

I’m glad you did, but that is disturbing on multiple levels how they handled that.

And it’s still a problem there. The FBI whistleblower protections and for the broader intelligence community are woefully inadequate and multiple attempts to improve them since I left the Bureau haven’t really been effective.

So let’s fast forward now to your new book, Policing White Supremacy: The Enemy Within, which you co-wrote with Beth Zasloff. Why did you decide to write this book?

During the first Trump administration, I had written a series of reports for the Brennan Center. One documenting the improper or lack of prioritization of white supremacist violence. This was at a time when many, in particular former Justice Department officials, were lobbying for a broad new domestic terrorism law and basically arguing that there was no domestic terrorism law. And that was the reason why the FBI was not more effective at policing white supremacist violence. But I knew from my own cases in the 1990s that we had more than sufficient laws and it was a matter of policy choices rather than a lack of authority and that the reason they were lobbying for a broader law wasn’t to target white supremacist law violence that they were ignoring, but to target other groups as terrorists, even though they weren’t committing the same kind of deadly violent crimes. So I wrote that report. At the time there was a lot of concern about hate crimes. So I wrote a report on how to develop new hate crime enforcement mechanisms. And ultimately the third in the series was a report on white supremacy in law enforcement. And because of those reports, I was asked to testify several times in congressional hearings. And then January 6 happened and the reforms we were asking for were not implemented in time. And unfortunately, law enforcement maintained its lax attention to these kinds of crimes, even as they were being planned in plain sight. And, you know, everyday people could just read the Washington Post and understand what was about to happen. And yet law enforcement appeared to have been completely flat footed and caught off guard. My publisher of my previous book, Disruptus, Discredit and Divide, how the new FBI damages democracy came to be and said, you know, with these reports as seed material, I think you could write a book about this problem. So that’s what I did.

And so you start off in the first chapter, you talk about the failure of police to properly respond to the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville in 2017, despite having accurate and timely intelligence leading up to the event, as well as having undercover officers in the crowd. Why did this happen? Why the inaction?

I think there are a lot of reasons. And we can go back through the history of law enforcement in this country and how they look at different kinds of advocacy groups or activist groups and groups that are challenging the status quo, the status quo political system, the status quo economic systems. Those are seen as a threat regardless of whether they use violence and law enforcement often sees them … It’s interesting the way law enforcement will talk about those groups as well that they present the opportunity for violence rather than looking at the violence that white supremacists engage in on a regular basis, even away from protest groups. It was interesting because when I was undercover in the 1990s, public violence wasn’t a successful strategy. To go out in public and commit violence meant the police could identify you. And once they identify one or two people able to arrest them, obviously they have a lot of power to get testimony from those people against others and it creates an opportunity for law enforcement to to take down a broader group of people. But in Charlottesville it appeared not just that they were unprepared for the violence that occurred, but I thought the silver lining would be okay, you know the violence happened, but it’s all on tape. I was sitting in my office watching most of it as as videographers and journalists were covering the events as they happened and live streaming those events. So you could actually see the people who were committing violence. Many of them already known to law enforcement because they had criminal records. I expected there would be a slew of arrests in the aftermath, but there really weren’t. In fact, the only federal arrest involved the homicide – Alex Fields killing Heather Heyer with his car. But they didn’t see other action. So it was really up to activists and journalists to highlight those cases and ultimately shame law enforcement years later into addressing those crimes. And that I realized again from my background that that lax enforcement was seen as a green light to these groups that, okay, we can come out in public and commit violence and use that as a recruiting tool. And as more violent protests began all over the country, we saw law enforcement often treating the white supremacists, the far-right militants, very friendly, in a very friendly manner while treating people from the community who came out to oppose them as the problem. And we started hearing this language around Antifa, that anti-fascists were the threat, that violent anarchists were the threat, where if you look at the history and the modern history of these groups, they’re really not engaged in deadly violence, very rare for that to occur.

So it demonstrated this problem of how government uses that violence in a way to entrench public policies. We saw police being rewarded and being authorized to use significant force against Black Lives Matter protests and other progressive groups, any groups led by people of color, tended to be targeted.

Charlottesville was kind of the coming out party for these groups and the fact that law enforcement didn’t respond as aggressively as it should, provided the opportunity for them to grow and to build national networks that ultimately enabled them to come, to bring thousands of people to the Capitol on January 6th willing to use violence to achieve their goals.

I mean, it seems like a really stark contrast between, you know, how the police treated the far right protesters in Charlottesville or even, you know, how some of the police reacted on January 6th to, like you said, like the full throttled militarized violent response to Black Lives Matter protests or the Dakota Access Pipeline protests at Standing Rock, which was led by Native Americans, or even the global justice movement, you know, the FTAA in Miami in 2003 or before that the WTO in Seattle in 99.

Right. And what was frustrating to me about that is I’m a child of the 60s and I grew up through, you know, where that violence was pronounced. And there were a lot of studies of how to properly police rowdy crowds and protest groups. And what they learned was an aggressive police response results in more violence. And just showing up in riot gear tends to agitate a crowd and lead to violence, much less once that violence occurs, if it’s done in an arbitrary manner, it expands the amount of violence and the amount of people that will engage in that violence. So sseeing that response in the twenty-teens, I knew this was intentional. This was something that they knew better, that they had the information to make better decisions about how to police these protests, but were choosing to come out violently and were being allowed to do that. Particularly in a place like Portland, you saw the police responding violently night after night and using tactics that were extremely arbitrary, you know, with this one tactic where they would, there’d be a standoff with protesters. Then you’d see the police just like rush them all at one time. And basically the only people who would get beaten or arrested were the people who fell as they fled – totally arbitrary and not achieving any kind of legitimate law enforcement purpose at that protest, but actually expanding the the number of people that would come out and protest the next night.

Well, staying on the topic of violence, let’s turn to a violent group that you write about quite a bit, the Proud Boys. Here in Philadelphia area, the Philly chapter was really active in the city and the surrounding suburbs. The Philadelphia chapter president, Zach Rheil, a son and grandson of Philly cops, is currently in prison serving a 15-year sentence for his role on January 6th. And on more disturbing, about 10 Proud Boys rubbed elbows with local cops outside a fraternal order of police lodge in Northeast Philly for a Back the Blue event in response to protests across the country in the wake of the police killing of George Floyd back in 2020. Why such an affinity between like this far right hate group and local police? Because it wasn’t just, know, Philly wasn’t some anomaly. You’ve documented the ties between these two groups across the country in your book.

Right, this was a common problem all over the country. And the Proud Boys were interesting, an interesting diversion from the way these groups operated in the 1990s, these far-right militant groups. Very early after the creation of the Proud Boys, Gavin McInnis, he talked about the group and was very clear that it was interested in violence, and at one point referred to them as a gang. And typically if you have a gang operating interstate and committing violence, law enforcement takes notice and the FBI in particularly would take notice where here it seemed that the FBI was absent completely. And as the violent incidents around the country grew, it became very clear that they were able to Proud Boys around the country to participate in various rallies in different localities. And what that allows is the development of logistics and networks. So it makes the groups more dangerous because they can move people around And the Proud Boys were also interesting as a group because they had some association with people close to government and close to the administration. That’s both local governments and the federal government and particularly in law enforcement. that was the reason I focused them on the book is because that was really the that bridge that these groups had long sought going back decades to have direct influence among people in power. And what you have to understand about white supremacy is these were groups and individuals who had their hands on the levers of government power and made policy and in many ways continued policies and to have groups that were willing to use non-state violence to support those politicians. It creates a very dangerous situation and very much authoritarianism 101. That’s how authoritarians gain power, is they employ a force of violent people to target their political enemies. And the Proud Boys were very good at kind of alleging their enemies was this Antifa force and government at the same time was targeting Antifa forces, although their imagination of what this was is very different from what it was in reality, which was mostly local people coming out to protect their communities.

So it was a marriage of government and violent non-government actors in a way that I think reflected the success of their tactics.

Yeah, and you even note that the FBI actually had informants in the Proud Boys, but rather than use them to collect evidence of Proud Boy crimes, they were tasked with reporting on their anti-fascist enemies.

Exactly. Again, it goes to how law enforcement could have possibly been so flat-footed on January 6th. One of the things I point out is the Hotel Harrington, which was a hotel in Washington, D.C., where the Proud Boys had congregated and engaged in some violence, shut down on the weekend of January 6th. It was willing to forgo revenue to avoid having their employees and guests threatened by these groups. So, if the Hotel Harrington has better intelligence than the FBI and federal law enforcement, we’re all in big trouble. But to find out during the trials that, in fact, they did have informants in the Proud Boys and in the crowd on January 6th, just like, Charlottesville, the Unite the Right rally at Charlottesville, these weren’t people unknown to law enforcement, right? Most of them are, many of the primary actors had had long criminal histories, violent criminal histories. And, there was one report released publicly that said that there were dozens of individuals that the FBI had placed on terrorist watch lists, mostly because they were violent white supremacists, attending the January 6 events. So how do you have dozens of people .. What is the purpose of a terrorist watch list if you can have dozens of them congregating for an event and no insufficient law enforcement attention to that?

And the Proud Boys were just one example where having those connections to the groups wasn’t in order to protect the public from the Proud Boys, but rather to target the enemies of the Proud Boys. Again, aligning of the government and non-government interests among these groups.

So these examples that we’ve talked about and others that are in your book, they unmask a kind of not only just implicit bias, institutional biases within law enforcement, whether it’s the FBI or local police, but there’s also a failure of these law enforcement agencies to police explicit biases within their members and within their ranks. Why is this happening? Why is this failure continually happening?

It was interesting to look at the history of implicit bias as a concept. And, and basically it came about after the civil rights movement when equal protection of the laws was, was the public policy. How do you explain the continuing racial disparities in every aspect of our lives, particularly in the criminal justice system and immigration? And this idea came up that, well, if the law doesn’t allow it, it must be accidental. It must be unconscious. It must be that the system is somehow bent in a way that allows this to happen. And I quote a number of implicit bias trainers who say that they go out of their way, not to mention explicit bias when they train law enforcement, that that’s something that law enforcement turns off and won’t, won’t cooperate with them in the training program. But if you’re a police officer who knows that one of the people in this implicit bias training is overtly racist and, and that officer is sitting next to you as they’re saying, talking about unconscious bias, it makes the whole thing kind of a joke – that this isn’t really something designed to address the racism that exists in law enforcement, but rather, just a procedure to make it look like we’re addressing it. And, one of the frustrations after my report on white supremacy and racism in law enforcement came out, I was asked to testify before Congress in a hearing, chaired by Representative Jamie Raskin, and he asked the FBI to attend because my report focused on two internal FBI documents, one from 2006 that warned about white supremacists infiltrating law enforcement, and another in 2015, which was a counterterrorism policy document that warned agents working domestic terrorism cases against white supremacists that their subjects would often have links to law enforcement. So, if the FBI knows this is such a problem that they have to warn their own agents, how come they don’t have a policy to address the threat this poses to communities policed by racist officers? And in fact, the FBI disavowed their prior intelligence and told Representative Raskin that they would not appear at the hearing because they didn’t see it as a significant problem. That was in October of 2020, just months before the January 6th attack that that included law enforcement among the attackers, assaulting law enforcement. It’s quite frustrating that, and has been … because of my law enforcement background, I get the opportunity often to talk to law enforcement audiences and then talking about these issues, I would always highlight to them that white supremacists kill police officers fairly regularly, too regularly. And that, you know, to the extent that they were strategically putting a blue lives matter patch on their sleeve didn’t mean that they wouldn’t kill you if you ever tried to get in the way of what they were trying to accomplish. It was unfortunate that they had to find that out in such a large event where so many law enforcement officers were injured. Even more frustrating that here years after the event, there is still a lot of denial about what exactly happened and whether law enforcement was harmed.

And we can’t even really pass legislation kind of, you know, addressing these issues. In 2022, the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act came up for a vote which would have mandated federal agencies to monitor and act against growing white supremacist and neo-Nazi activities, both within the military and federal law agencies. And, you know, that failed to pass. And then you even had like here Bucks County, someone who at least promotes himself as a moderate and bipartisan problem solver, Congressman Brian Fitzpatrick, who is a former FBI agent, voted against this.

Yeah. And even when there are successful efforts in 2019, Congress passed a portion of the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act. There was a reporting requirement where the FBI was required to document the number of domestic terrorism incidents that occur in the country, the number of fatalities resulting from that incident the number of resulting investigations, indictments and convictions broken down by category. The FBI, even though it often says that it doesn’t investigate ideologies, it only investigates violence, its domestic terrorism program is divided by category. So when I was working undercover, they had a category for white supremacists. They had a category for anti-government militias. They had a category for anarchists. But when Senator Durbin introduced the Domestic Terrorism Prevention Act that you mentioned, seeking that information, they scrambled up their categories. So they put white supremacists in a category with what they then called Black Identity Extremists. So that if you got the data, it would be difficult to disaggregate it to see how they were using their tools. My belief, based on public evidence we have from the various non-government groups that collect this information, is that the white supremacists and far-right militants are far more active in the number of incidents and far more deadly in how those incidents impact society. And if you looked at that data broken down by the original categories, it would have showed white supremacists and far-right militia groups are the most serious threat. And groups like animal rights activists and anarchists are really not much of a threat. So it would be harder to justify having the bulk of investigations targeting groups that were less violent and it would put more pressure on the FBI to fully investigate white supremacist groups. Even once they mangled the categories, in 2019, Congress passed it as part of the National Defense Authorization Act of 2020, which required them to report every year this data. And the FBI in reporting it would say, we don’t collect domestic terrorism incident data, or the fatalities that result. Here, counterterrorism is the number one priority of the FBI. How is it that they don’t know how many incidents occurred? Likewise, they said they couldn’t give accurate information about the indictments and convictions in these categories. Every year the FBI reports to Congress, a bank robbery report. They say how the person got into the bank, whether they used a weapon, how much money they got, how they got out of the bank, tremendous detail about every bank robbery that occurs because they have jurisdiction to investigate those bank robberies. But somehow in their top priority, they don’t even bother to collect incident data. And my belief is that the reason why is because they want to be able to choose who they investigate and prioritize investigations based on internal biases about which ideologies they oppose rather than actually looking at the violence.

We now find ourselves in an even more precarious position with Trump’s reelection, right? To be clear, this has been like a bipartisan failure throughout multiple decades. But with Trump and Project 2025 and the nominee for FBI Director, Kash Patel thinking that the FBI is somehow woke, despite everything we’ve talked about and what you’ve documented in your book. What’s at risk now moving forward? How much worse can this get?

I have found that I’m not very good at predicting the future. So, what I can do is say what happened in the past. And what we saw in the past is, is that the Trump administration was very clever in the way that it encouraged a violent form of policing, and a violent non-law enforcement cadre. And I imagine that will continue. And I imagine the FBI under whoever is the new director will continue prioritizing groups that the white supremacist attack rather than white supremacist violence. And one thing I should make clear is that I don’t think white supremacists believe Donald Trump is a white supremacist. They are exploiting Donald Trump the same way he is exploiting them. And there’s a dialogue going on in the white supremacist movement about how far they can take this association with the governing officials. And, you know, when you look at something like the Pittsburgh synagogue attack, that was an example of somebody who said, okay, I see our effort to cabin our language so we can fit into political society is not effective. I’m going in, and screw the optics. I’m going in. That was kind of an articulation of this idea that these groups are not, they realize that the Trump administration is not going to take them to their goals and much the way they were able to buddy up to law enforcement at all these violent protests. But when push came to shove on January 6th and the police told them, no, they were happy to attack police just as they had been attacking community members across the country. So, I think it will be an interesting four years, because it’ll be interesting to see when these groups don’t get everything they want, how they react. And, you know, so much of this is opportunistic where, you know, anybody who has access to a high powered rifle can take a shot at somebody. And we’ve seen that and how that plays out … And you mentioned project 2025 and the efforts to change the FBI. Some of them I would have to applaud, you know, having the FBI focus on the violent crimes, yes, you should know how many domestic terrorist incidents happen and how many people are killed by them, because how else can you properly devote your resources to the most serious threats? You know, to the extent that, you know, I don’t see this administration doing anything different than the previous Trump administration where you had political appointees at the Department of Homeland Security, for instance, according to DHS whistleblower in the intelligence and analysis unit, telling them to, no, no, no, we want you not to report on white supremacist violence and instead highlight reports on anti-fascist violence. So I think there will be a transition period. I’ll be interested to see what happens with Trump’s promised pardons of the January 6th rioters who were convicted. Obviously there’s a significant law enforcement audience that would be very distressed by that. Either way, there’s the opportunity to disappoint one of your base groups. So it’ll be interesting to see how the groups react to those kinds of challenges.

Well, Mike, thanks so much for joining us. I want to encourage everyone to go to your local bookstore and you can pre-order a copy of Policing White Supremacy: The Enemy Within, and it will be released on January 7th. Mike, thanks again for joining us on The Signal.

Thanks so much for having me.