This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, independent news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. It is republished with permission. Sign up for their newsletter here.

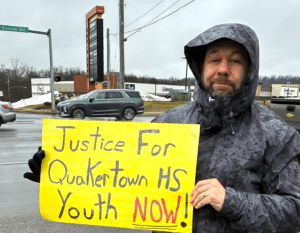

PHILADELPHIA—As energy wonks descended on a downtown hotel for a hydrogen conference, witches were waiting for them in the parking lot. Donning a black, horned hat and green face paint, Delaware Riverkeeper Maya van Rossum and a coven of fellow protesters played off the release of the movie “Wicked” to lambast what they see as voodoo: green hydrogen.

“Don’t believe the hydrogen hype!” they chanted to passersby last month.

The tone was in stark contrast to a celebratory press conference President Joe Biden hosted in the city a year earlier, announcing a federal investment of $750 million in the region to build out one of seven hydrogen hubs scattered across the country. Politicians including Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro and U.S. Sen. Bob Casey hailed the announcement of the Mid-Atlantic Clean Hydrogen Hub (MACH2), as did a menagerie of local officials and union leaders. The hub, they said, would bring new life to rusting industrial areas in southeastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey and Delaware by integrating them into a “clean hydrogen” economy, delivering reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in sectors like manufacturing and transportation while also creating thousands of jobs.

That vision now hangs in the balance. Technically, Biden’s announcement in October 2023 was only an intent to award; funding negotiations are ongoing between the U.S. Department of Energy and a consortium of would-be recipients. In the interim, a collection of environmental groups in the region, including the Delaware Riverkeeper Network and Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, have taken up opposition, contending that the promises of MACH2 are oversold and that the hub, if it proceeds, could harm fenceline communities while potentially exacerbating global warming instead of easing it.

But likely scarier to supporters of the hub are economic and political headwinds.

Over the past year, experts say, the costs of creating truly “green” hydrogen—produced using 100 percent renewable energy—have risen. That’s spooked some players from the space and created cracks in the foundations of MACH2 and other hubs before the mortar even had time to dry. Part of the problem, experts say, is hand-wringing over the long-awaited release of Treasury Department rules on federal financial incentives for hydrogen production, now expected this month, which could impact producers’ bottom lines. And now that former President Donald Trump is headed back to the White House, some fear the entire federal initiative could go up in flames—hubs, tax credits and all.

“There is a huge potential for Trump’s lack of focus on emissions or decarbonization [to] hinder progress of hydrogen hubs,” said Bridget van Dorsten, a principal analyst studying hydrogen at the consulting firm Wood Mackenzie. “Without funding, we may continue to see partners pull out of hubs.”

It all sets the table for a crucial month, stretching from the holidays through Trump’s inauguration on Jan. 20. For the Riverkeepers, the fear is that the Biden administration will rush the $750 million award out the door before then, starting the ball rolling on a plan they say hasn’t been properly vetted. For MACH2, it’s the prospect of the bottom dropping out entirely.

The Logic and Challenges of “Clean Hydrogen”

“Clean hydrogen” is a divisive option for reducing climate emissions, with some championing it as a wonder fuel of the future with a wide range of potential applications and others lambasting it as a meritless front for the fossil fuel industry.

Matthew Krayton, a spokesperson for MACH2, said hydrogen’s role should be pragmatic, helping to decarbonize the 15 percent of the economy that represents the hardest sectors to abate. The remaining emissions, he said, can be cut by electrification and renewable energy.

“I think we all wish that we had some sort of easy button that we could hit in order to solve the climate crisis, but we don’t,” Krayton said. “We think clean hydrogen is part of an all-of-the-above energy transition strategy. Is clean hydrogen right for every single application? Absolutely not. It’s a targeted tool.”

Experts are mixed on whether MACH2, along with the greater hub model, would be useful in developing hydrogen’s potential. Members of the Zero-carbon Energy systems Research and Optimization (ZERO) Lab at Princeton University say they see merits. Mohamed Atouife, a doctoral student at the lab studying green hydrogen’s applications in heavy industry, said the fuel is one of only a handful that can decarbonize sectors like steelmaking. That’s because fossil fuels have traditionally been used to generate chemical reactions during the production process, which wind turbines and solar panels can’t replace.

But pricing is the problem, and government intervention is essential to finding a solution, Atouife said. Green hydrogen, which uses wind and solar to split the gas from water through a process called electrolysis, is significantly more expensive than the current industry standard of cleaving hydrogen from methane and casting off carbon dioxide as a byproduct. The Inflation Reduction Act, passed in 2022, generates a tax credit for green hydrogen producers meant to close most of the cost gap. But that still leaves significant uncertainty about who would buy the finished product, which Atouife said the administration has tried to address by also seeding money to build working clean hydrogen economies.

“This is going to be a mishmash of mush,” said Zulene Mayfield, the leader of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living. “In my opinion, it’s nothing but a money grab for the fossil fuel industry.”

“This was the beauty behind the hydrogen hubs,” Atouife said. “The federal government is going to come in and try to actually connect suppliers with buyers.”

The margins were always going to be tight in Philadelphia, where a lack of renewable abundance compared to the Sun Belt makes that energy inherently harder to leverage for green hydrogen. But over the past year, the picture has grown bleaker. Globally, Atouife said, the capital costs of building green hydrogen plants have proved more expensive than anticipated.

That squares with analysis by van Dorsten. While the industry analyst forecasts green hydrogen will grow from less than 1 percent of the total hydrogen market today to more than 80 percent by 2050, she said there are signs of stress in the current moment for the nascent industry.

“It’s quite a difficult thing to get all of your ducks in a row, for which hydrogen has many—a whole flock,” van Dorsten said.

The challenges have prompted some companies to cancel projects and slow what had been a rapid year-over-year increase in green hydrogen proposals around the world. Van Dorsten said that could lead the industry to focus on what it will take to actually make green hydrogen work.

But there is no sugarcoating the potential impact of a Trump administration.

“The hydrogen market … is unlikely to move forward because the political landscape remains relatively unpredictable,” van Dorsten said. “Hydrogen hubs could face setbacks if the Trump administration were to rescind unspent funds or loans.”

What Will Happen to Hydrogen Hub Money?

MACH2’s plan, according to its application to the Department of Energy for hydrogen fund money, is a build-out of about 20 facilities across the Delaware Valley, with notable backers including multinational oil and gas pipeline company Enbridge, a bevy of regional natural gas utilities including Philadelphia Gas Works and Chesapeake Utilities, and a pair of public transportation agencies. But according to MACH2’s website, several projects have since been scrapped. Messer, a multinational industrial and medical gas company, backed out of plans to build electrolysis facilities in Pennsylvania and Delaware. sHYp, a green hydrogen company focused on using seawater in production, similarly abandoned plans for an electrolysis facility in Wilmington, Delaware.

Perhaps most ominously, MACH2’s website says HRP Group, a real estate company overseeing a $4 billion redevelopment of a former oil refinery site in Philadelphia, has delayed plans to use green hydrogen for power and steam generation in new buildings. The company is described as an “anchor offtaker” for green hydrogen in the region in MACH2’s application materials, which show it as accounting for as much as 71 percent of demand within the hub.

Asked for comment about the economic headwinds facing green hydrogen and the Philadelphia-based hub, MACH2 did not respond.

It’s in this fog of uncertainty that opponents of the hub are afraid mistakes will be made. It hasn’t been easy to stay on top of MACH2 developments as it is, said Tracy Carluccio, deputy director of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network. She said MACH2 did not initially make its application materials public until the Riverkeepers successfully obtained them through an open records request, and members of MACH2 typically only meet in venues that require expensive entrance fees to gain access to.

Krayton counters that MACH2 has been forthcoming, sharing materials and responding to questions from environmental groups while meeting with stakeholders across the region. Without naming specific individuals, he believes some are so dead set against the hub that no amount of transparency will suffice.

“At a meeting in Philadelphia … there were protesters outside. A gentleman was holding a sign that said, ‘No clean hydrogen,’” Krayton said. “I’m not sure what level of transparency would ever change your mind.”

Through open record requests, the Riverkeepers also ascertained that early in the application process, MACH2 stated an intention to use “blue hydrogen,” a process not yet proven at scale to use fossil fuels to produce hydrogen and lower emissions through carbon capture. MACH2 has since clarified it no longer plans to use blue hydrogen.

Still, the perilous economics surrounding green hydrogen prompts opponents to say funding should instead be directed to proven technologies such as renewable energy generation.

Abbe Ramanan, a project director at the Clean Energy Group, a national nonprofit focused on the energy transition, acknowledges that green hydrogen has a role to play in industries like aviation and maritime shipping where electrification “doesn’t really make sense.”

“But the scale of buildout that we’re seeing,” Ramanan adds, “as well as the use of things like blue hydrogen, and extending the life of fossil fuel assets by combusting hydrogen, we don’t think those are good uses of federal dollars or the renewable energy it would even take to make the green hydrogen.”

Whether or not those federal dollars will actually arrive in Philadelphia remains to be seen. Carluccio worries that the Biden administration will rush to award the funding before the Trump administration arrives, a scenario that some experts say could indeed protect it from adversarial appointees of the new administration, but others doubt will actually happen.

For Zulene Mayfield, the leader of Chester Residents Concerned for Quality Living, a nonprofit focusing on environmental justice in Chester, Pennsylvania, it feels like a distinction without a difference. Frontline communities there have for decades dealt with the noxious pollution from industry—a dynamic that could continue under green hydrogen, which for some applications casts off nitrous oxide as a byproduct. Mayfield hasn’t been impressed by MACH2’s interactions with potential host communities so far, and the involvement of oil and gas companies raises red flags for her.

“This is going to be a mishmash of mush,” Mayfield said. “In my opinion, it’s nothing but a money grab for the fossil fuel industry.”