Americans United, while not taking a position on economic policies, is actively fighting against the Shadow Network, a “clandestine web of Christian Nationalist organizations, conservative billionaires and powerful political allies at all levels of government” working to “upend democracy and equality by undermining the separation of church and state.” This is the backstory of the economic and Christian currents that ultimately produced the Shadow Network.

In the heart of the Great Depression in 1934, Dr. Eli Ginzberg, a young economics professor, weighed in on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s transformative fiscal agenda.

Overwhelmingly elected to the presidency two years earlier and already beloved by a great majority of Americans, Roosevelt, during a period of 25% unemployment, had steered the federal government into previously uncharted territory: the creation of federally funded social safety nets for financially disadvantaged citizens, including public service works jobs and housing assistance. He had also announced his intention to establish a social safety net for aged citizens. (This would come to pass with the Social Security Act of 1936). Big business interests and many wealthy Americans complained that FDR had abandoned capitalism for socialism or even communism. Ginzberg, though, knew better.

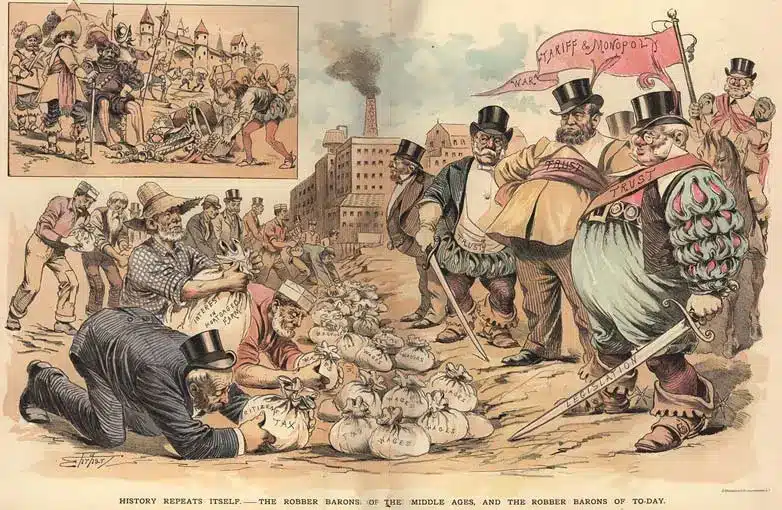

During the 1920s, Presidents Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover had essentially turned the federal government over to corporations, dramatically cutting taxes on wealthy Americans and declaring victory, even as some one-half of all Americans remained in poverty. Corporations drove up profits by creating installment plans for middle-class customers, driving consumer debt to unprecedented levels.

The resulting inequality led to the stock market crash in 1929 and the Great Depression. Confident that inequitable capitalism would correct the economy, Hoover nonetheless bailed out banks and railroads. At the same time, he turned a cold shoulder to ordinary Americans, ignoring pleas to use federal coffers to ease the dire plight of the millions of unemployed, homeless and destitute. Trounced in his 1932 re-election bid, Hoover argued that his failed economic policies adhered to Adam Smith’s classic 1776 tome, Wealth of Nations.

In 1934, economist Ginzberg in a New York Times article set the record straight. Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Ginzberg admonished, “is not a justification of modern [plutocratic] capitalism.” In addition, the economist continued, “[H]ad Adam Smith been afforded the opportunity to review the problems of corporate enterprise in 1931,” he wrote in his book The House of Adam Smith, “there is little doubt that his general approach would have been the same as in 1776: namely, a preoccupation with the public welfare.”

In fact, Smith, considered the father of capitalism, approached economics from the perspective of the common good. In Wealth of Nations he identified greed as the greatest impediment to national prosperity. Seeking to banish extreme wealth inequality, Smith advocated for higher tax rates for wealthy persons, government regulations of businesses and banks, and restrictions on how much family wealth could be passed from generation to generation. He also advocated for what we now call living wages. “A man must always live by his work, and his wages must at least be sufficient to maintain him,” Smith wrote. “They must even upon most occasions be somewhat more; otherwise it would be impossible for him to bring up a family, and the race of such workmen could not last beyond the first generation.”

Smith was critical of excessive commercial profits: “[Businessmen] complain much about the bad effects of high wages in raising the price, and thereby lessening the sale of their goods, [but] they, say nothing concerning the bad effects of high profits.” To level the economic playing field, “[t]he rich should contribute to the public expense, not only in proportion to their revenue, but something more than in proportion.”

INTERVIEW: ‘Christian Nationalism Is on the March’ and Is a Threat to Inclusive, Multiracial Democracy

In short, Smith opposed unfettered capitalism, instead proposing an empathetic system of capitalism that prevented massive, nation-destroying wealth gaps between the rich and the poor. For his part, Ginzberg in 1934 noted that Smith’s Wealth of Nations “like the New Deal … seeks a general redistribution of wealth.” Smith’s empathetic capitalism was designed to prevent poverty. In his own words, Roosevelt noted his objective in emulating Smithian capitalism was to “save the people and the nation” from the economic failures of the plutocracy-focused [rule by the wealthy] presidencies of Coolidge and Hoover.

Unsurprisingly, much of the business world of the 1930s harshly criticized FDR’s federal government for siding with ordinary working Americans over large corporate profits. Less known is that many white Christian clergy — Protestant and Catholic alike — also sided with exploitative capitalism and condemned Roosevelt’s empathetic capitalism. Many complained that the federal government had usurped the traditional role of churches in helping destitute persons — failing to acknowledge that churches during the Great Depression were woefully incapable of alleviating the human carnage caused by corporate greed.

To the extent that many church leaders had their heads stuck in the sand of obliviousness, they could in part thank Bruce Barton, a Christian advertising executive and former publicity agent for both Coolidge and Hoover.

Barton in 1925 had published one of the nation’s top-selling nonfiction books, The Man Nobody Knows: A Discovery of the Real Jesus. In the book, Barton proclaimed Jesus to be “[t]he Founder of Modern Business,” an evangelist of modern capitalism. But the real reason nobody had heard of Barton’s Jesus was that he did not exist until Barton invented him. Jesus, in the gospels an itinerant preacher and teacher, never thought about capitalism and was not a businessman. Nor should Barton’s fictitious book have been on the nonfiction list. Nonetheless, Barton’s fake Jesus became the basis for the Gospel of Wealth, an extreme capitalist theology marrying Christianity to greed.

Partially conditioned by Barton, millions of white Christians during the Great Depression preferred Adolf Hitler’s authoritarian Nazism over Roosevelt and Smith’s empathetic capitalism. Far-right prominent Christian clergy spearheaded an American Nazi movement condemning Roosevelt as a Socialist and a Communist. Two of the most popular American Nazi organizations were named the Christian Front and the Christian Mobilizers. Allied Christian radio programs spewed messages of hate to millions of listeners. From within this movement the phrase “Christian nationalism” emerged to describe adherents’ goal of making America an unfettered capitalist Christian nation — by violence if necessary.

Opposition aside, Roosevelt’s unprecedented four-term presidency imposed record-high tax rates on wealthy Americans, reigned in corporate excesses, birthed unprecedented worker protections and created our nation’s first universal social safety nets. Smithian capitalism implemented in FDR’s presidency transformed American governance, capitalism and Christianity.

READ: Legislating Inequality: The Christian Confederate Roots of Project 2025

Nonetheless, Christian Nationalist opposition to empathetic capitalism grew all the greater. In the late 1940s and the 1950s, many Christian businessmen and economists alike, envisioning a Christian America, set about repositioning Smith as an unfettered Capitalist, a false portrayal of Smith common to the present day. Millionaire businessmen financed a 1950s libertarian Christian journal — Faith and Freedom — for preachers. R.J. Rushdoony, extremist Calvinist and emerging founder of a Christian Nationalist movement called Dominionism, contributed to the periodical.

In addition to enabling Rushdoony, wealthy Christians funded the rise of a young and charismatic evangelist, Billy Graham. In the words of historian Kevin M. Kruse in One Nation Under God, they transformed the evangelist into “the most prominent of the new Christian libertarians.”

During his revival crusades, from the pulpit and in writings, Graham preached against labor unions and touted the godliness of unregulated capitalism. Writing in the journal Nation’s Business in 1954, Graham declared “that faith and business” could be a “profitable mixture …. Thousands of businessmen have discovered the satisfaction of having God as a working partner.”

Financed by extremist corporatists, Graham bashed communism, brought souls to the altar of capitalist Christianity and led the way in convincing Congress to add the words “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance. Evidencing his stubbornness, he supported demagogic anti-communism U.S. Sen. Joseph McCarthy to the bitter end. Apart from integrating his revival meetings, the evangelist largely stood by as Black Americans demanded, and by hard work and blood secured, equal rights in the 1960s.

In the early 1970s, as Christian corporatist-allied Graham found a receptive nest within Richard Nixon’s White House, many of America’s top corporations inaugurated systemic lobbying of Congress for legislation favorable to business interests at the expense of middle- and working-class citizens. Seeking to curtail the federal government’s growing social services expenditures, well-placed Christian Nationalists and corporate allies established the Heritage Foundation (architect of Project 2025).

In the 1980s, corporate interests and white Christian Nationalists alike celebrated when, at their behest, President Ronald Reagan promised to eradicate FDR’s legacy of empathetic capitalism. Reagan made good on his word. Erasing both FDR and Adam Smith, Reaganomics redistributed wealth upward from the poor and middle classes to enrich the wealthy all the more. Most significantly, Reagan cut the top marginal tax rate from that of 91% in the 1950s and 73% upon his election to 28%, the lowest since 1925 — the same year Bruce Barton created his fake capitalist-worshiping Jesus as the leader of a new theology, the Gospel of Wealth.

Since Reagan, more and more billionaires have allied with Christian Nationalists in a quest to destroy America’s inclusive democracy and replace it with a plutocratic theocracy. In October 2024, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis released statistics on the state of U.S. wealth inequality. “The top 10% of households by wealth had $6.9 million on average,” it noted. “As a group, they held 67% of total household wealth.” By way of vast contrast, the “bottom 50% of households by wealth had $51,000 on average. As a group, they held only 2.5% of total household wealth.”

Statistics released from various studies in 2024 reveal that many workers would have to work for hundreds of years to equal their CEOs’ 2023 salaries. That same year among the nation’s top 100 companies, the “median C.E.O.-to-worker pay ratio was about 300 to one,” according to executive compensation research firm Equilar.

Where do those ungodly profits go? As reported by Nicholas Powers in 2022 for Truthout, a vast network of Christian Nationalist organizations are primarily funded by “a 1 percent of megadonors and corporations.” With their vast wealth, this Shadow Network of one percenters bought a Christian Nationalist U.S. Supreme Court, brought an end to Roe v. Wade and are bent on tearing down the United States’ constitutional separation of church and state.

“The reality,” writes Powers, “is that some of the richest people and corporations in the world bankroll Christian nationalists who, in turn, attack the already limited freedoms of poor people, people of color, women and LGBTQ people in the name of God.”

In the intertwined world of plutocracy and Christian Nationalism that is today’s United States, the empathetic capitalism of Adam Smith and Franklin D. Roosevelt is no more. Absent, too, from Christian Nationalism is the inclusive, compassionate and empathetic Jesus of the gospels.

In 2025, plutocratic theocracy is poised to assault America’s constitutional foundation of church-state separation as never before through the implementation of their extremist Project 2025 agenda.

This article was originally published in the July/August 2024 issue of Church & State magazine, a project of Americans United for Separation of Church and State. It is reprinted here with permission.