Tyree Wallace grew up in South Philly, around kids who got in trouble. He knew they were trouble. In the case of Brian Brooks – the man who bought his own freedom by falsely accusing Wallace of the 1997 murder of local shop owner, Jhon Su Kang – Tyree regrets the alliance. He speaks incredulously of his 19-year-old self’s decision to hang around with Brooks, “He wasn’t a good person, and I knew it. I knew he was a scumbag but, [I thought] he’s not going to scumbag me. I’m just glad someone didn’t kill both of us just for walking around with him.”

Tyree has different friends now.

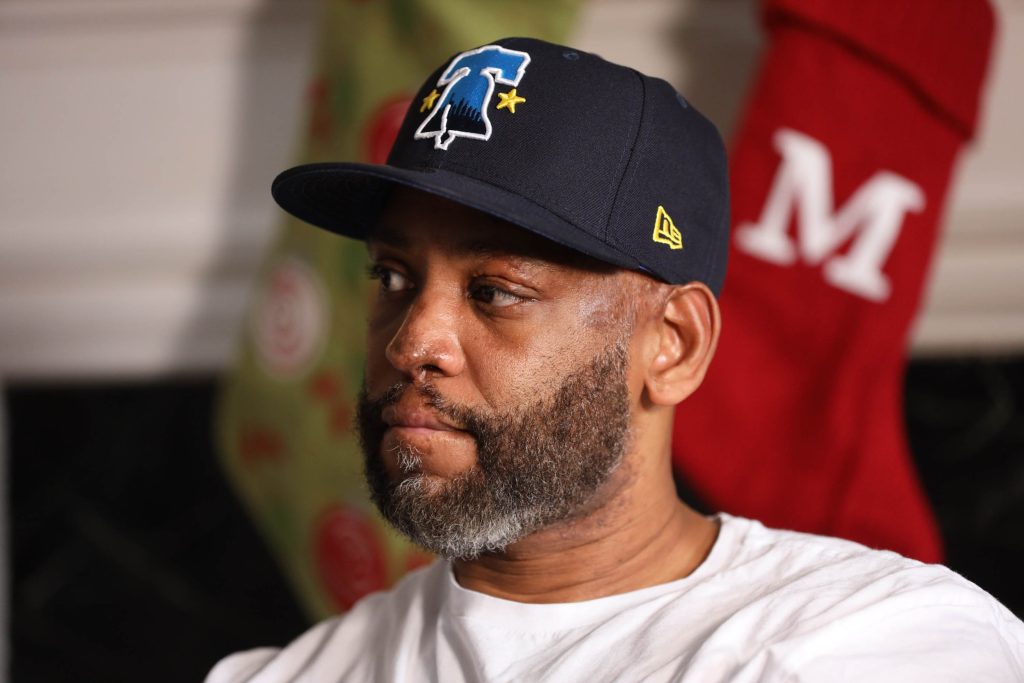

On Christmas Eve, at the home of attorney Keir Bradford-Grey, Tyree Wallace sat down with the Bucks County Beacon to discuss his recent release from prison and the 20th Century nightmare scenario that led to his incarceration. Prior to Wallace’s November 4 release, he’d spent 26 years in prison for murder – nearly 60 percent of his lifetime.

And now, after more than two-and-a-half decades of declaring his innocence, Tyree credits Bradford-Grey and another attorney, David Perry, along with a massive social network of supporters and justice advocates for finally freeing him from jail.

One might expect that a wrongly incarcerated man – abused by a system slavishly dedicated to process with insignificant regard for justice – would air a laundry list of grievance and pain. To the contrary, Wallace – when not discussing the details of the case, catalogued the individuals and organizations that worked in tandem to secure his freedom. As for anger? Wallace’s character doesn’t cut that way. Lucky for him! It was that unquenchable desire to find a productive outlet – no matter the adversity – that caught the eye of David Perry.

Perry first approached Wallace to protect the intellectual property of his MANN UP program and ultimately quarterbacked Wallace’s struggle for freedom.

But that’s the end of his incarceration – here’s how it began.

On October 27, 1997, 17-year-old Rahim Shackleford shot and killed Jhon Su Kang in an armed robbery. At the time of the murder, Wallace had never met Shackleford and was not implicated in the crime. In fact, alibi witness Damon Milligan testified that Wallace and he were at Maddie McQueen’s – the home of Milligan’s mom – playing cards with friends on the night of the murder.

So how did Wallace get framed?

The day of Kang’s murder, Wallace’s friend Brooks had been taken into custody for a string of armed robberies. Bradford-Grey explained that earlier, “Brian Brooks was brought into the police department on a domestic violence case with his girlfriend. His girlfriend had called the police on him and then she was so upset with him, she told the police that he had committed robberies in that neighborhood. The police then confronted him with all the evidence against him … armed robberies that had gone on.” Bradford-Grey said that once in interrogation, Brooks “ends up confessing to those.”

READ: Pennsylvania’s Inadequate Funding of Public Defenders Is Unconstitutional, ACLU Suit Claims

Bradford-Grey and Perry tallied the time Brooks would have served for his actions, totaling the years for each offence. Perry said that Brooks would have gone away, “The rest of his life.”

Facing the likelihood of dying in prison, Brooks met repeatedly with the police. He continually implicated others in his own crime spree, hoping to get reduced sentences. Because of the details of those offences, none of his allegations worked. At his third police interview, in December of 1997, Brooks offered the detectives information on a murder that had happened back in October – a murder he only learned about after-the-fact because on the day it occurred, he was in custody confessing to his own crimes.

Bradford-Grey explained that the Philadelphia DA’s office, namely Assistant District Attorney Yvonne Ruiz, ignored the impossibility of Brooks’ accusations. “You have to think about it. Who’s going to care about Tyree? He’s 19 years old, not politically connected, not connected to power brokers and is in a neighborhood that has been disinvested in and is a the disposable area for these systems, when [that system] wants to say, ‘we work.’”

Bradford-Grey, now Head of Civil Rights Litigation for Marrone Law Firm, added, “That’s really what it boils down to. I was a public defender during that time. I saw it time and time again. And I’m so glad that we’re in another era of consciousness because no one came into those courtrooms to see what was going on. [Back then] there would be Tyree and his lawyer and a slew of law enforcement, but on the other side there’s nothing. Now you see the community coming into the courtrooms to get more of a bird’s eye view of the type of justice that’s being delivered, and I think they should do that a lot more.”

But in 1999, “another murderer off the streets” fit the profile the DA’s office wanted to portray, even if the scenario was impossible and the actual murderer was already in custody.

So, Brooks named Wallace as a conspirator who premeditatedly planned to rob and kill Jhon Su Kang. With zero evidence, two suspects already in custody – men who never mentioned and did not know Wallace – the prosecution gave Brooks a deal. They reduced his sentence and pursued Wallace, arresting him the following month and charging him with second degree murder.

Brooks’ 60-year sentence was cut to five.

Wallace’s trial – one of the many in a long line of frame ups that preceded the dismissal of his prosecutor ADA Yvonne Ruiz – who presented no forensic evidence and hung on Brooks’ conjured testimony – even though Brooks himself couldn’t continue the façade.

“How do you say you’re sorry to a guy like that? To apologize? It’s just not enough.”

Following his testimony, Brooks confided in Philadelphia County Sheriff’s Deputy John Hamilton that he had lied. Hamilton spoke to the Bucks County Beacon this week from his home in Georgia, “I was assigned to bring the witness. I brought him back [after his testimony] and he says, ‘Sheriff, you got a minute? What’s the penalty for perjury?’ I told him, five to ten and he says, ‘Everything I said on that stand was a lie.’”

After telling the judge what Brooks had said, Hamilton was assigned to another courtroom. Later in the trial, the judge called the deputy to the stand. “I’ve done so many homicide cases, most of them you don’t remember. But this one I remember. Because this guy said he lied because of the detective.”

Wallace’s own account of the detective’s harassment matches what Hamilton recounted on the stand. “I had a police officer, Charles Boyle, who looked me in my face, telling me he knew that I didn’t commit the crime, but that he didn’t give a fuck that I was going to go to jail for it anyway. That I was going to spend the rest of my life in prison.” Boyle left the Philadelphia detective’s unit six years later – after only 13 years – and finished his career working at a nearby university’s public safety department.

Hamilton grieves what happened to Wallace. “The whole time he’s pled his innocence.”

As for his testimony recounting Brooks’ lies? “People busted my balls. Called me an inmate lover.” Hamilton didn’t waiver. “I became a sheriff, sure to enforce the law, but also to protect the innocent. I was just doing my job. The correct way. The proper way. I know people say all the time, our justice system sucks. Well, sometimes it does.”

One day, not long ago, Emily Barkann an intern working on the Post Conviction Relief Act (PCRA) – one of the many people on Wallace’s thank-you list – reached out to Hamilton, “Emily called, and I got a call from a guy in New Jersey, and I told them exactly what happened. I’m glad if I had some small part in getting him out. Now I’d like to someday hook up [with Wallace] and break bread and talk about our dreams.”

For now, Wallace’s dreams are quite simple. He dreams of exoneration – a world in which he’s no longer held to account for things he never did. But – with one last insult added to 26 years of injury – in order to walk free, Wallace was forced to plead guilty to a lesser charge related to the crime. “They made me put up my right hand. Everybody in that courtroom knew that it was lie, what I was about to say, including the judge. But they made me hold up my hand and say, ‘I swear to tell the truth.’”

Eventually, after spending essentially his entire adult life in prison telling the truth, Wallace agreed to lie. The falsehoods were extracted from him in much the same manner as the lies Brooks told that put Wallace in jail in the first place. In the end, Wallace agreed to lie so he could secure his freedom. “The reality was, I had spent 26 years in prison. I needed to be home. I didn’t want to spend another 26 minutes in prison.”

Wallace is a victim of a justice system that often succeeds when individuals purchase their freedom with lies – so long as those lies lead to the incarceration of another – whether the accused is guilty or not. And that system finally got Wallace to purchase his own freedom with lies he agreed to tell about himself.

Bradford-Grey and Perry acknowledge the injustice of insisting Wallace admit guilt, basically to hold harmless the commonwealth that stole his freedom. The government – in coercing a criminal confession – hopes to dodge accountability for the damage done to an innocent man.

For now, Sheriff Hamilton summed up the tragedy of a judicial system that shows no remorse. “I don’t know how you can make up for 28 [sic 26] years. How do you say you’re sorry to a guy like that? To apologize? It’s just not enough.”

“The reality was, I had spent 26 years in prison. I needed to be home. I didn’t want to spend another 26 minutes in prison.”

Bradford-Grey and Perry agree, it’s not enough. These two attorneys and their colleagues on the ground, in the media, and at Second Justice where Bradford-Grey’s devotes much of her time, will continue their fight for judicial accountability.

Meanwhile, Wallace, who founded not one but two non-profit organizations helping inmates live better lives, has the dream of building SRC (Systemic Reformative Change) into a nationwide advocacy group.

Now, better than anyone, Wallace knows that the country needs structural change. “America is run by systems, criminal justice system, healthcare system, the banking system. Everything you’ve been thinking of [to make things work] is a group of people sitting in a room making decisions for everybody else. I’ve wanted to learn about systems, how they work. What can we do to implement them? I’ve spent a lot of time in a cell, and I was able to sit down … and build things out with flow charts. After about two years, I came up with SRC.”

For Wallace, Systemic Reformative Change is his next dream.