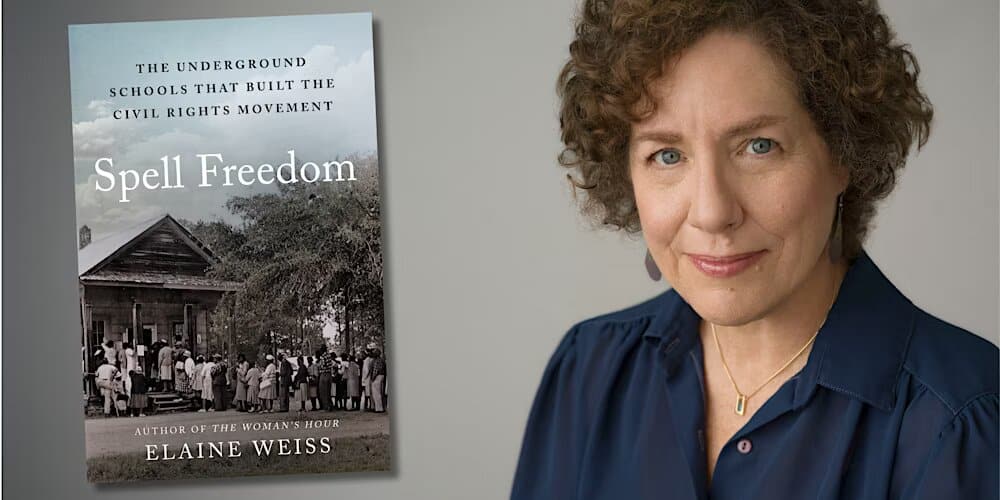

Elaine Weiss is an award-winning journalist, author, and public speaker. She is the author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote and Fruits of Victory: The Woman’s Land Army of the Great War. She joins us today to talk about Her new book, Spell Freedom: The Underground Schools That Built the Civil Rights Movement, which comes out March 4th. Her book, which tells the story about how four ordinary citizens through social movement organizing affect change, offers valuable lessons for today as the country finds itself engaged in a new Jim Crow moment and a renewed battle over Civil Rights.

(Also listen on Apple, Spotify, Podbean, and iheart)

TRANSCRIPT

Before we talk about your book, I wanted to ask you about your career as a journalist and author. How did you fall in love with writing and reporting as well as American history? And where has this taken you during your career?

I think I always liked recording stories, taking them down, my relatives, interesting people I met, even as a child. And I really fell in love with journalism in high school. I was on my high school newspaper. I pursued in college, I pursued American history and literature. So I immersed myself in American writing and the world in which it was created. So I had a sense of that. And then I went to graduate school in journalism at the Medill School at Northwestern. And I came out knowing I didn’t really want to work for a daily newspaper. I didn’t like the rush of it. I didn’t get the adrenaline thrill of a scoop.

I liked the deeper story. I liked the analysis. I liked the human interest aspect. Not fluffy, but again, I was a political reporter. And so I worked as a political journalist in Washington. I worked for a congressman. I’ve had, as writers do have, and you may be able to appreciate this, many different sorts of writing careers. One of them was actually in Philadelphia, for several years, and I worked on a publication that explored corporate responsibility, which was a term at that time. It has been forgotten a little bit now, but it was urging corporations to do their part as world citizens.

And then I have always wanted to do a larger project and flirted with writing a book in my 20s and that didn’t quite work out. I did write it, it’s not been published. Anyone wants it, the manuscript is here. It’s on these huge disks, know, remember those disks. But I also worked as a journalist. I was a magazine editor. I wrote many freelance newspaper and magazine stories. I worked in public radio. I wrote freelance obituaries.

I made my life as a scrivener. Then later in my career, I had the opportunity to be able to concentrate on writing longer pieces, more analysis of social and political change. And so this is my third book. The first one was about American women organizing themselves to save the crops during World War I. And the second was called the Woman’s Hour. And that was about American women organizing to win their right to vote. And now Spell Freedom is about Black citizens, many of them women, who organize to reclaim their voting rights in the Jim Crow South.

So like you said, your new book, which comes out on March 4th is Spell Freedom: The Underground Schools That Built the Civil Rights Movement. How did this grassroots or social movement history make it on your radar and why did you decide to write about it?

I’ve thought about … once you get enmeshed in a book for six years, you almost forget how you arrived there, but there is a very clear path. When I was writing about those women’s suffrage movements of the early 20th Century, and my book The Woman’s Hour concentrates on the last political battle, which was the ratification of the 19th Amendment, in the last state, which was Tennessee. And all the forces come to bear there. And so it was a great framing for writing that book. And I toured around the country, I made hundreds of presentations and talks. And I was always asked, well, what happened to the 19th Amendment for Southern women, for Southern Black women? They were not allowed to vote, even though the Constitution now said they could.

And I would explain that it was not the 19th Amendment’s fault. Actually, that was a misnomer that I saw in the media a lot and I had to try to correct it. It is not the 19th Amendment that makes that restriction. It was the state legislatures in the Southern states, which imposed the Jim Crow laws and basically disenfranchised Black women just as it had disenfranchised Black men after the ratification of the 15th Amendment. So Black citizens definitely had the right to vote and were suppressed and were violently kept from voting. So as I explained this, I realized I didn’t know what happened in between. I know the Voting Rights Act then restored voting rights with federal enforcement, but I didn’t know what happened in between. And I felt that lack and I started to research it and came across this amazing story about a very little known aspect of the Civil Rights movement, which was training very poor and illiterate Black sharecroppers and factory workers to pass the literacy tests, which were imposed upon Black citizens, but not white citizens, in the southern states at this time. This was talking about the 1930s, 40s, 50s and early 60s. So I realized that this was a way to explain what was happening and to put a wonderful spotlight on this very courageous, creative way of fighting Jim Crow, basically with pencils.

And then I found that these citizenship schools, as they’re called, those are the underground schools, and the people who created them, and the teachers and students who participated in them really became the engine of the Civil Rights movement. And so I realized I had found a really not well known part of the Civil Rights movement, which was really, really important. And to me, very

pivotal to how change is made in a democracy. And that’s what I like to see. I like to explore in my books how is change possible, and what is required of citizens to make change.

There are four main characters that drive your story, although a great supporting cast as well. But there’s Septima Clark, Esau Jenkins, Bernice Robinson, and Miles Horton. I was wondering if you could give listeners just a thumbnail sketch of each character and their importance to the story.

I’d love to do that because these are names you probably have not heard of when the history of the Civil Rights movement of the 20th Century, of course it keeps going on, but what we call the Civil Rights movement, which was in the mid 20th century. And these are not names that are familiar. These were not important, famous people, but they’re the living beating heart of the movement. And Septima Clark, when the book opens in 1954, is a 56-year-old Black woman who is a school teacher. She’s been a school teacher for 40 years in the segregated school system of South Carolina. And she’s been an activist all this time in the NAACP. She’s participated in lawsuits and in pressing for equal pay for Black teachers, for all kinds of improvements and reclaiming of civil and social rights. And she’s frustrated though, because things are not moving very fast. This is now 1954. But the book opens on the day that the Brown decision is announced. And that is certainly not the beginning of the movement. It didn’t just start then, but it is a catalyst and it does mark a pivot point when a lot of things happen and that’s why I started there. And she goes on to use her teaching skills, her activist skills, to create this very important citizenship school project.

Esau Jenkins, who is the next character, is perhaps the most fascinating of all, he is a son of the Sea Islands. He comes from John’s Island off the coast of Charleston. He had only formal education, if you could even call it that, up to fourth grade, because what happened in rural areas in the Jim Crow South was the sharecropper economy, which was basically an extension of slavery. And the sharecropper family, part of their agreement with the landowner, and these were still called plantations, actually pledged the labor of their children to, they were forced to. And so children could go to school and again, they would have to trek for miles and go to a dilapidated shack which had no running water, no seats, no blackboards, cast off textbooks.

He only had a fourth grade education, but when he entered adulthood, he went back and he got night school education. And he began to realize that his island, his family, his neighbors were poor and impoverished and had absolutely no say in the way their lives were run and the justice system was totally slanted against them. And he decides that they have to vote. If they’re going to have any power, they have to vote. And he decides, one of his little … he’s an entrepreneur, has lots of little businesses besides his farm. And he has his wife type up the South Carolina constitution, which is required. You have to be able to read it and interpret it, that’s also the subjective part, to be able to register to vote. And he he trains his bus riders to be able to basically memorize the South Carolina Constitution. And as far as I’ll go with that, he’s just a fascinating man who becomes a real regional leader in the Civil Rights movement.

He is on the board of the NAACP and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He’s just this fascinating and creative and brave man who comes from the Sea Islands.

The third is a beautician, Bernice Robinson, who again is sensitized to the racial discrepancies, the racial discrimination and oppression of her family and her neighbors in Charleston. And she lives in New York for a short time. She sees that Jim Crow is not everywhere. In New York, you can ride the buses. You can go to the theater and not have to sit in what’s called the crow’s nest, the upper balconies. And she comes back to Charleston because family matters.

And she says, we don’t have to live this way. And she becomes an activist with the NAACP. And her beauty parlor becomes sort of an NAACP outpost. And she encourages her women customers to join and allows them to use her beauty parlor as a mailbox. So their husbands or their pastors or their employers don’t know that they belong to the NAACP, which was considered a subversive organization to the white establishment in the South.

And the fourth is an intriguing person named Miles Horton. He is a white, liberal Tennessean, born in Appalachia, who has graduate training in philosophy and sociology and divinity. And he comes back to his home turf in Tennessee, in the mountains of Tennessee, and he establishes something called the Highlander’s Folk School. And this begins as a labor organizing training facility because it trains people to not many ideology, but to learn from one another, to speak with one another, to live with one another for a week or two in workshops, and to articulate what the problems are in their communities jointly, communally come up with answers and then sends them home with a blueprint and supports them in that way. And by 1950, 52 Horton has decided that racial matters and integration, I should say desegregation, first step desegregation, and equal rights and voting rights is the most important problem in the South. And so he pivots the Highlander School to concentrate on Civil Rights. And it becomes one of the most important sort of nerve centers for the movement. It’s the place where strategy is discussed. It’s the place where Black people and white people actually live together for a few weeks at a time and talk honestly with one another both Rosa Parks trains there, John Lewis comes there as a young divinity student, and you see the effect of Highlander all through the Civil Rights Movement. So those are my four main characters. There’s also a federal judge who’s really quite fascinating, a white federal judge who decides he’s going to dismantle the legal foundations of Jim Crow law in South Carolina.

There’s a staff folk singer who spreads the music of the movement. So I was blessed with some very rich, prominent characters who you’ve never heard of before.

And the Highlander Center is still active today.

It is, it’s in its 93rd year of operation, began during the depression in 1932. And it is still training social and political activists in the South to tackle problems. And so it’s not, it doesn’t impose, you know, it doesn’t go into the field itself, but it trains and it supports those who are in the field. And it’s quite an extraordinary history of Highlander and what I talk about in the book is not only does it help develop and sponsor the first citizenship schools, but it also again becomes this nerve center for the movement and it is also attacked by the government of Tennessee, by the FBI, by the Klan.

And you see the stakes that were evident in the Civil Rights movement. One of the things that shocked me was the systemic persecution of anyone who even tried to register to vote. It was not just Bull Connor in the streets with his dogs. It was not just at the Pettus Bridge in Selma.

It was everywhere.

It was insidious.

It attacked American citizens.

And I really talk about that and the persecution of Highlander, calling everything that was threatening to the white supremacist status quo in the South was called communist. So you have the Red Scare and McCarthyism entering into this, which actually played a very big role. And Martin Luther King was hounded with that accusation just to delegitimize his leadership. And that was just used, we hear it today, something that is not understood or not liked, was called socialist or Marxist, and it just these terms are thrown around with very little grounding. So, I found that a very chilling but important part of writing.

Yeah, he might even be accused of being woke today over that.

Yes, exactly. Very woke, which really just means awakened, which I think we should all aspire to.

Absolutely. the history that you’re writing about, what does it tell us about how change is made in a democracy, something you had mentioned before?

When I wrote about the suffragists, I would say, you know, this was a long process. It took seven decades and three generations of women to finally win the right to vote. With the Civil Rights movement, of course, that timeline gets expanded greatly. And the milestones are in some ways a little harder to say, well, we’ve achieved it here and we’ve achieved it there because we haven’t achieved it completely yet. But I use some of the goals of the mid-century movement to demarcate progress. So everything is moving towards getting the federal government to finally enforce the constitution. Hello… and that manifests itself in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. So those become, to some extent, the goal, not the complete goal, but a goal, two goals. And so we see the movement marching, literally marching towards that. What I came away as the writer with is it, again, it takes a very long time. And, but it takes grassroots organizing. In the movement, there’s a tension and an argument about charismatic leadership. Does the movement need Martin Luther King? And within the movement, there’s discussion of that. Does it need a charismatic leader or, and or it needs leaders on the ground in every community. And part of what the citizenship schools did was to cultivate and support local leaders.

There are other parts of movement that do that. Certainly the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee does that. But the idea of to make change, it actually has to be in your mind first. It has to be within you that you are both entitled and capable of making change. And so in my book, the entitlement, the agency comes from literacy. Once people who have not been allowed to be educated because of the racist system learn to write their names. I mean, it’s as simple as learning to hold a pencil becomes the first step. Once they can hold a pencil, and again, they break them at first, because they’re not used to holding this little piece of graphite. Once they can sign their names and can sign documents, once they can learn to read even rudimentary, they don’t have to rely on their employer or their neighbors to read to them. There’s this great sense of empowerment, and liberation comes when they can see themselves as citizens. And so part of what these citizenship schools do is they make people psychologically ready to become first class citizens, not only giving them the skills they’ll need, but also psychologically. And it was this building up community by community. These are not big schools. are these could be in your, these literally were in garages and beauty parlors around tables and church basements. These were tiny classes and they were run by your neighbors. These were local people. They weren’t people coming in from outside. They were local people who’d been trained by Septima Clark. And they are teaching your neighbor, teaching you, and again, your neighbor may just be two weeks ahead of you in the reading comprehension. But again, was this community, teaching community to stand up and they taught constitutional rights and they taught, how does government work? If you have a complaint because your road hasn’t been paved because you’re in the black section of town, who do you go to? Who runs the government? And so was civics, it was government structure. They practiced writing letters to their congressmen and their legislators. This is how change is made, but first it has to be mental. First it has to be grasping what’s possible. And part of the importance of the Highlander School is that it gave people who attended there, the Black people who attended there, a sense of an integrated world because they were living with white people who were respectful. They ate at the same table together. When John Lewis comes as a 19-year-old seminary student from Nashville, he comes for a weekend workshop with Reverend Lawson’s students who will then become the nucleus of the SNCC movement. They, for the first time he says, he ate with white people next to them at the same table. And that just blew his mind. Rosa Parks, the same thing. She had never sat at a table with white people, live in the same dormitory rooms, all these forbidden things, and that opens up a whole world. That’s part of the mental change that happens. So I think making change on so many levels, it’s the personal and then it’s the community, and then it’s seeing a national movement, and then it’s gaining enough traction and enough support that demands can be made at the federal level in Congress. It’s a long road, it’s a bumpy road, there’s lots of pain, there’s death, there’s blood, there is disappointment, but the sense of what is possible and what is feasible is important to making change in a democracy. Change isn’t slashing things. Change isn’t tearing everything down. Change is imagining how this can be better.

Now, Jim Crow had to be torn down.

But it had to be done by the people. It had to be standing up, sitting in, waiting in, lying in. It had to be shown how ridiculous the system that prevailed.

And this grassroots model for change, within our democracy and this popular education model, this was a bottom-up approach rather than a top-down, which they applied even to the schools themselves, correct?

Yes, yes, exactly. Yeah, this was, and one of the things I think is valuable about this story is that you’re seeing the movement through the eyes of these four activists and how they move through the movement because they do, they enter into the larger movement. They inform the larger movement, they affect it. But it’s really seeing it from, the perspective is from the grassroots.

And so I spend a lot of time talking about activists in … Mrs. Vera Pigue in Mississippi, who’s this fantastic organizer and fearless leader who personally desegregates the Greyhound stations and conducts, forms interracial concerts in town. mean, all these forbidden, forbidden things.

And her house is attacked by night riders. And the next day she’s right back out there. There’s so many of these people who I, again, I don’t, I can’t explain their whole lives, but I do mention what they’re doing. And I think it’s important to realize what ordinary people had to sacrifice or willing to commit themselves to at the local level.

Because one of the things that really shocked me, truly, truly shocked me, is again, the kind of pressure that was put on anyone who tried to rattle the system. And let me just give you an example of what a grassroots person, I wouldn’t even call them activists, just a concerned citizen, just someone who wanted to be a full citizen. So I have… maybe I do know how to read and write, maybe I don’t and I go to a citizenship school to learn to do that. I have to go to the registrar’s office in a Deep South town. The registrar, it’s open only a couple of hours a month. I’m a worker, I have to take time off. I can’t tell my employer what I’m doing. I go there and let’s say I take the literacy test, I’m literate. I may even have a college education. And by the time I leave and go home, the registrar has called my employer and I am fired. The registrar has called my landlord or the plantation owner where I have a sharecropper’s cabin and my family is evicted.

Or if I own the house, my mortgage has been pulled, the loan for my car has been pulled, the pharmacy will no longer fill the prescriptions for my sick baby, the white doctors in town will not treat my pregnant wife or my ill husband. Your life is ruined because you have decided to try to register to vote. This happened tens of thousands of times all over the South. And it was orchestrated by … this came from the governor, from the state legislature, and from your own mayor and city council. They were often members of what was called the White Citizens Councils, which were professional doctors, lawyers, white doctors, lawyers, bankers, statesmen who met and agreed that they would suppress any Civil Rights activity in their locale. They would use all of their economic and political power to do that. And they did it. And you had no recourse. Again, if your name was published in the paper, you were put on a blacklist, and people had to move, people were killed. So this more insidious, quiet, economic, it was called the squeeze, I found just horrifying. And that’s not a part that I had ever encountered in my readings. It wasn’t visceral enough to move me the way reading these accounts did. So yes, there was physical, terrible physical violence, but there was more than that. There was people lost their jobs, people lost their houses, people lost their families. And I think that has to be remembered. That’s part of the bravery of grassroots organizing is that they knew this could happen and they went, they believed in democracy so completely that they were willing to risk it.

I feel like the publication of your book couldn’t be coming at a better time right now. Sadly, almost, as we’re seeing a real backlash against the racial progress that the country has made over the last 70 years. And even more so than a backlash, I feel like there’s an explicit effort to resegregate American society.

And this is something that’s, you could say is happening with the current administration’s war on DEI, Diversity, equity, and inclusion, right? About including Black and brown people in our institutions, in our businesses, in our universities. And we’re seeing real rollbacks happening in real time right now. And this is something that I feel like would make the White Citizens Council that you had just mentioned or the supporters of the Southern Manifesto, very happy. You’ve talked a little bit about some of the lessons. Are there any other lessons that we can take from this history that you wrote for us and apply that today?

Yes. Oh wow. Yeah. Every day I’m thinking about this. I wrote the book in the last several years and it was powerful enough just the story itself. I thought I would dedicate six years of my life to doing this. But in the last few months, it’s taken on a whole other dimension. And I saw a headline yesterday where the perspective cabinet post for the education department was asked whether a course in Black history would be legal to teach. And she said, she really didn’t know if it was going to be legal. I just, I couldn’t quite sit in my chair. We’re in a very dangerous moment, as everyone knows. I don’t have to tell anyone in your audience that.

I think the lessons I can see, and yeah, this is a book about diversity, equity, and inclusion. That’s what America is supposed to be about. It doesn’t have to have a label. It doesn’t have to have that particular, we could call it patriots for democracy, because that’s what it is. And to deny that is to want to deny history. You Black history was not allowed to be taught in many schools. I mean, it was explicit, it was implicit. I write about some teachers who were fired because they tried to teach about W.E.B. Du Bois or, well, actually, yes, Du Bois or any Black leader. And they were fired because you’re not supposed to talk about that.

And we’re back to that. You’re not supposed to talk about things that might make some people uncomfortable. I won’t go into a tirade about the uses of history and the importance of history, but in a more practical sense, yes, the idea of these citizens councils, which were the cream of every Southern city and town, belonged to these. Your congressman belonged, your mayor, your, again, your legislator, your pastor belonged. Your banker belonged. So where do you go? Who is going to represent you to fight against this? And I think a lot of us, white and Black, all of us are feeling it right now. Who is going to represent us? Who is going to help us stand up to this? And I think that it has to come from a great groundswell of the people, but I also think we do need those in power who see the dangers of this to stand up and to use whatever legal means they have, whatever popular and persuasive means they have. You talked about the Southern Manifesto and that’s come to mind a lot as the Senate has the Congress has rolled over and is advocating its responsibilities and its constitutional role in government. And for those who are not familiar, the Southern Manifesto was signed by 101 congressmen I believe … more than 100 members of Congress most from the southern states and basically saying we’re not listening to the Supreme Court ruling on Brown. We are, we don’t have to listen to it. It was a constitutional crisis at that moment. And the movement coalesces to try to annul that. But

Again, it was a resolution, it’s not law, but it showed the attitude of a good portion of Congress. And it was a real low point in our political history. And I think if that manifesto in a modern form was proposed today, we’d also see it signed by too many of our elected representatives. So I think, the lessons I can point to is the personal quiet bravery of the people I’m writing about. A school teacher, a beautician, a small businessman, a white man who called himself a radical hillbilly. These are the people I think who are the true patriots. And I think we have to redefine what a patriot is. Septima Clark at one point in 1956, publishes something called Champions of Democracy, where she tries to give credit and to make known people she has met in the grassroots who are standing up for American ideals.

And Rosa Parks is part of that. The boycott in Montgomery was still going on. She writes about this in this brochure that was published and disseminated by the Highlander School. And it’s very moving because this middle-aged school teacher saying, this is America, this are the champions of democracy. It’s not Strom Thurmond, it’s not our legislators who are signing the Southern Manifesto. These are the people who represent America and who are gonna save it.

I can’t write a prescription, I don’t know, but I would hope that that sort of counter narrative, and again, a lot of this is about narrative – counter narrative will emerge and take hold. And we can say we’ve done this before and yes, we have, but now the alarm bells should be ringing.

Well, one lesson that gives me hope from your book is that grassroots and movement organizing creates change. And education is the first step to organizing. So I want to encourage readers to educate yourselves about this neglected, if not forbidden history and go to your local bookstore and order Spell Freedom: The Underground Schools That Built the Civil Rights Movement, so that you can apply this history to the struggles that we’re facing today. Elaine, thank you so much for coming on The Signal and thank you for writing this extraordinary book.

Thank you, Cyril, it was real pleasure.