Let’s get this out of the way up front. The Montgomery County Board of Education set themselves up for this. But now the Supreme Court decision in Mahmoud v. Taylor joins the list of rulings kneecapping public schools and crushing more of the rubble piled up where the wall between church and state used to stand.

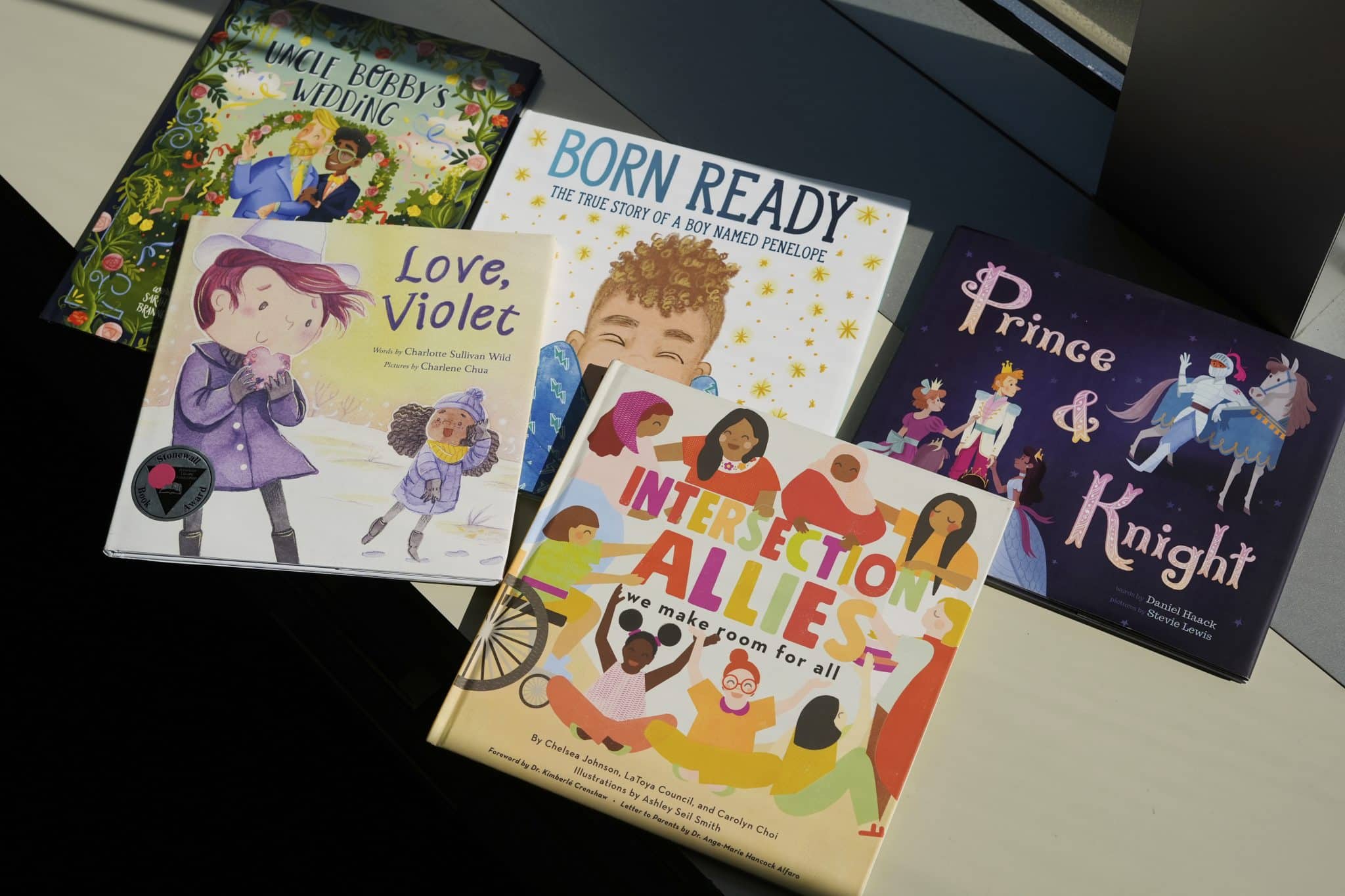

AFT President Randi Weingarten herself posted that the case “should have been worked out on the local level.” The Maryland school district, in a 2022 attempt to improve and broaden its representation, added 13 new inclusive books, five of them which included LGBTQ characters. This triggered push back from parents in what Religion News Service called the most religiously diverse county in the United States. The district has a variety of policies in recognition of that diversity, including opt out policies. But a year after the new books were introduced in grades K-5, over loud community objections, the board ended the opt-out policies for those books.

And so this lawsuit was brought by several sets of parents (Muslim and Catholic) and the group Kids First. The legal team is Becket Fund for Religious Liberty, a group that has gone 8-0 before SCOTUS in the last 13 years (including Burwell v. Hobby Lobby).

The United States District Court for the District of Maryland found: “Even if their children’s exposure to religiously offensive ideas makes the parents’ efforts less likely to succeed, that does not amount to a government-imposed burden on their religious exercise.”

The United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit upheld the lower court 2-1, stating, “simply hearing about other views does not necessarily exert pressure to believe or act differently than one’s religious faith requires.”

But the Supreme Court were having none of that.

Samuel Alito for the Majority

Alito joined Justices Roberts, Thomas, Gorsuch, Kavanaugh and Barrett in ruling against the school district, arguing that the government cannot condition the benefit of a free public education on the parents’ acceptance of instruction that poses a “very real threat” of undermining the religious beliefs and practices that parents wish to instill in their children.

The majority agreed with the plaintiffs argument which rested heavily on the 1972 decision in Wisconsin v. Yoder. Wisconsin Amish had contested the state’s compulsory education law. The state required school attendance through age 16, but the Amish withdrew their students after eighth grade. The court found in favor of the Amish in this case, and the precedent was the backbone of Mahmoud’s argument.

Alito noted repeatedly that the court has “long recognized the rights of parents to direct ‘the religious upbringing’ of their children.” But Alito’s argument does not rest on specific practices or requirements to “make an affirmation” contrary to parental religious beliefs. Instead, Alito’s interpretation of Yoder is much broader:

Rather, the threat to religious exercise was premised on the fact that high school education would “expos[e] Amish children to worldly influences in terms of attitudes, goals, and values contrary to [their] beliefs” and would “substantially interfer[e] with the religious development of the Amish child.”

In other words, Alito’s argument is that Yoder was decided not based on schools requiring specific non-Amish practices, but simply the prospect of exposing Amish teens to non-Amish vibes.

Alito reminds us that some Americans believe that “biological sex reflects divine creation,” that marriage should be man and woman only, even, as one plaintiff family put it, “sexuality is expressed only in marriage between a man and a woman for creating life and strengthening the marital union.” After noting some of the content in the books, Alito writes (quoting Yoder):

These books carry with them “a very real threat of undermining” the religious beliefs that the parents wish to instill in their children.

“Very real threat” is doing very heavy lifting. There are some other specific points raised about the books and the district guidance on how to handle the lessons, most relying on an incomplete and selective explanation of those details (much as Kennedy, the case of the praying football coach was decided on counterfactual details). But to appreciate what the majority has done here, it is perhaps best not to get too far into the weeds.

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent argues that the Free Exercise Clause prohibits government “from compelling individuals, whether directly or indirectly, to give up or violate their religious beliefs” and prohibits “laws that have a tendency to coerce individuals into acting contrary to their religious beliefs.” The majority “rejects this chilling vision.” While Alito fails to clearly express his alternate vision of what the Free Exercise Clause means, he certainly seems to mean that anything that the school does that in any way contradicts parents in any way, thought, word or vibe, violates Free Expression rights.

In response to the argument that parents are in no way prevented by teaching religious beliefs and practices at home, Alito whips up this retort: “According to the dissent, parents who send their children to public school must endure any instruction that falls short of direct compulsion or coercion and must try to counteract that teaching at home.”

He points out that many parents have to send their children to public school, that public schools must be available absent any conditions, and that the school exercises much influence over impressionable children (an argument that the majority rejected in the Kennedy case).

The appendix to Alito’s decision includes selected pages from one of the books, Uncle Bobby’s Wedding, plus information from BookNotes, the website linked to Moms For Liberty to target books for banning.

Clarence Thomas Adds His Two Cents

Thomas has added a separate concurring opinion, the point of which appears to be mainly to use his favored “historical precedent” argument. When Yoder was decided, he observes, compulsory high school was a relatively recent development, which makes a bit of sense if you think that in 1972, the end of World War I was also a recent development. But he races on ahead to argue that sex education and health classes in schools is also recent, so therefor undeserving of any kind of legal support.

Sonia Sotomayor for the Dissent

Sotomayor writes for herself, along with Justices Kagan and Jackson. And she is extraordinarily unimpressed by the majority opinion.

The Free Exercise Clause commands that the government “shall make no law . . . prohibiting the free exercise” of religion. U. S. Const., Amdt. 1. “The crucial word in the constitutional text is ‘prohibit,’” for it makes clear “‘the Free Exercise Clause is written in terms of what the government cannot do to the individual, not in terms of what the individual can exact from the government.’” Lyng, 485

Exposure to an idea is not coercion (and she tosses in their own decision in Kennedy, where they argued that having the football team pray on the fifty yard line at the end of a game wasn’t going to coerce anyone).

Sotomayor argues that the majority gets Yoder all wrong. The Amish ran afoul of compulsory high school attendance not because of non-Amish vibes, but because Amish teens are to spend their teen years becoming part of the community while learning the tasks of farming and housekeeping.

The problem in Yoder was not that the law exposed children to material that would incidentally “undermine” religious beliefs, but that it compelled Amish parents to do what their religion forbade: send their children away rather than integrate them into the Amish community at home.

Sotomayor also picks out the majority’s creation of the “very real threat” test that “triggers the most demanding level of judicial review.” If the court rejects Sotomayor’s straightforward argument that Free Exercise has been violated when a parent is required by law to violate or give up their religious beliefs, then how is a court supposed to judge when a family’s Free Exercise rights have been violated?

The majority declares the inquiry will turn on several context clues: the “specific religious beliefs and practices asserted,” the “specific nature of the educational requirement or curricular feature at issue,” the age of the children, and the context and manner in which the relevant materials “are presented.” On that last point, the majority adds, courts should ask whether the materials are “presented in a neutral manner” or “in a manner that is ‘hostile’ to religious viewpoints and designed to impose upon students a ‘pressure to conform.’”

They might as well have included “consult Magic 8 Ball” on the list. As Sotomayor writes, “that test lacks any meaningful limit.”

To demonstrate, she turns back to Uncle Bobby’s Wedding. The majority suggests, both directly and cherry-picking pages from the book, that the book pushes a “subtle” normative message. For example, they show that upon the wedding announcement, niece Chloe is not happy, and that the book means to shame the character. In fact, the book is primarily about her concern that getting married will change her relationship with and access to her favorite fun uncle. The story is far more focused on dealing with fears of children that a marriage will change their family; the fact that Uncle Bobby is marrying another man is an incidental detail. The book’s “very real threat” is that it treats same-gender marriage as unremarkable.

Alito also cites half of the guidance on teacher-student discussion of the topics, presenting the teacher part of the script without including the student statement that the teacher lines are meant to respond to.

Sotomayor writes, “if even potentially imagined ‘coy’ messages hidden in a picture book are sufficient to trigger strict scrutiny when they conflict with a parent’s religious beliefs, ante, at 23, then it is hard to say what will not.” Particularly, it’s if one can cherry pick the pieces of the “message” to further your own aims.

The decision opens the floodgates for an uncountable number of religious objections to classroom materials, and to prove it, Sotomayor lists an assortment of lower court cases. It’s long, but instructive:

See, e.g., Mozert v. Hawkins Cty. Bd. of Ed., 827 F. 2d 1058, 1062 (CA6 1987) (religious objections to “biographical material about women who have been recognized for achievements outside their homes,” lessons on “evolution,” and teaching “children to use imagination be yond the limitation of scriptural authority”); Fleischfresser v. Directors of School Dist. 200, 15 F. 3d 680, 683 (CA7 1994) (religious objections to materials containing “‘wizards, sorcerers, giants and other unspecified creatures with super natural powers’”); Altman v. Bedford Central School Dist., 245 F. 3d 49, 56, 60–63 (CA2 2001) (religious objections to activities involving, among other things, yoga, meditation exercises, and the Drug Abuse Resistance Education (DARE) program); Moody v. Cronin, 484 F. Supp. 270, 272 (CD Ill. 1979) (religious objections to “mandatory coeducational physical education” that requires children to “view and interact with members of the opposite sex who are wearing ‘immodest attire’”).

Nor would this be limited to books. A teacher’s wedding photo, a child’s report on their family, or even a poster saying “All are welcome here” could all trigger a judicial intervention.

Sotomayor also points out that while this lawsuit is seeking a non-democratic solution to the issue, back home in Maryland, democratic processes are in play. Three of the board members were unseated in the last election.

And the result?

All you have to do is say, “It’s against my religion,” and you get full veto power over your local school district.

Your district may avoid the issue one of two ways. This case leaned heavily on the lack of opt out for the offending materials. This solution creates procedural challenges for the school. How do you keep track of who is opted out of what, and where do you send them to sit while the lesson continues without them.

Many districts will expand what they are already doing to avoid controversial topics—complying in advance and telling teachers to avoid even a whisper of banned topics.

So which would be worse for a child with an LGBTQ family or identity? To be in school and never see a hint that the life they know exists, or, whenever the topic comes up, to see a bunch of classmates stand up and walk out.

In the meantime, consider this take from Rex Huppke at USA Today:

I have a deeply held religious conviction that, by divine precept, lying, bullying and paying $130,000 in hush money to an adult film star are all immoral acts.

So it is with great thanks to the U.S. Supreme Court and its recent ruling allowing Maryland parents to opt their children out of any lessons that involve LGBTQ+ material that I announce the following: Attempts to teach my children anything about Donald Trump, including the unfortunate fact that he is president of the United States, place an unconstitutional burden on my First Amendment right to freely exercise my religion.

Finally, a warning for people of faith

There is one other predictable outcome. A whole lot of folks are going to step up to demand their newly-minted Constitutional right. Flat Earthers, religion-based racists, and, of course, the Satanic Temple will all demand their say, and to deal with it, government will either be drowned in a deluge of silly requests, or we will get a Government Department of Religious Oversight, and religious folks will have to line up to find out whether the government recognizes their religious concerns as real or not.

This decision provides yet more cover for bigotry draped in the fig leaf of religion, and in doing so, devalues religious faith even as the government quietly puts itself in charge of religious exercise. This is only going to get uglier for everyone.