The site of the 1-million-square-foot Amazon data center will be at the Keystone Trade Center located at 1 Ben Fairless Drive, which is currently being redeveloped by NorthPoint development. Amazon’s $20 billion investment in Pennsylvania to expand its data center infrastructure for AI and cloud computing rides on the coattails of Governor Shapiro’s Lightning Plan, an “all-of-the-above”plan to bolster energy production.

Reported environmental effects of large-scale data centers include significant local water straining, accelerated carbon-dioxide emissions and consequential electricity consumption. In the meantime, the Pennsylvania ranks 49th in the US for renewable energy growth.

Aside from its environmental effects, data centers have caused a hike in electricity rates for local residents. A report from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found that West Virginian ratepayers will “pay more than $440 million over the next 40 years” for high-voltage transmission projects for incoming data centers. Similarly, in Pittsburgh, Duquesne Light’s default electric rate rose about 15% partly due to the price to secure power-generating capacity on the PJM grid, and in 2024, PJM predicted that large users such as data centers could double their megawatt usage by 2030.

Quentin Good, a Frontier Group policy analyst who studies and has written about data centers, explained that when one customer is responsible for major infrastructure investment, regulators aim to assign the costs directly to them rather than the general public. However, this does not always happen, and costs could be diverted. “The cost for upgrades to the grid can be passed on to customers, and we’re already sort of seeing that happen, especially in PJM’s region,” Good said.

Ginny Marcille-Kerslake, a Pennsylvania organizer for Food and Water Watch based in Chester County, has firsthand experience of halting a data center initiative at the local level. In East Whiteland Township, Green Fig Land Company is planning a data center of up to 2 million square feet. And in West Whiteland Township, where Marcille-Kerslake lives, the developer of the data center attempted to obtain a zoning ordinance amendment to allow for data centers or power generating facilities in a certain district so he could power his incoming data center in the neighboring township.

Marcille-Kerslake soon learned the plant was to be a hydrogen power plant, which has a larger greenhouse gas footprint than simply burning methane. She and a friend proceeded with collecting hundreds of signatures and herded a few hundred people to attend a hearing, and they additionally garnered media coverage. The developer withdrew his application for the zoning ordinance amendment, which Marcille-Kerslake said would have “flung the doors open” for a data center-fueling power plant and more possible data centers being built in a certain district of West Whiteland.

“At the local level, if we still have the proper tools, we can stop these things,” Marcille-Kerslake said.

The data center in East Whiteland Township will only create 50 permanent “good-paying jobs” along with 3,000 construction jobs, according to the developer Charlie Lyddane. Governor Shapiro, State Senator Steve Santarsiero, State Representative Jim Prokopiak and Bucks County Commissioner Bob Harvie have all touted job growth as a benefit of bringing the data centers to PA and Falls Township, but Marcille-Kerslake said she believes this is an echoing of fracking’s false job growth promises.

“These projects are primarily creating short-term construction jobs,” Marcille-Kerslake said. “These are the lowest density employers, these data centers … So the jobs thing are these same false promises we hear over and over again.”

State Rep. Prokopiak pushed back against the alleged uncertainty of job growth at the center.

“There’s a need for 24-hour security in these situations. There’s also landscaping and support jobs and building maintenance jobs … And certainly construction jobs are needed, too,” Prokopiak said.

As for the environment, Prokopiak emphasized that the data center’s location used to be a former steel plant which already had a negative impact on the environment.

“All business has an environmental impact,” Prokopiak said. “It’s repurposing that land, which for many purposes we can’t use it for, into something that benefits all the community.”

Prokopiak added that because 90% of Americans have a smartphone, the need for large-scale data centers is evident.

“At the end of the day, it’s a part of progress … And, like it or not, as we see AI come into play, there’s going to be more data centers,” Prokopiak said. “These data centers are going to go someplace. It’s better to have some here where it has less of a negative impact on a community than someplace else [such as] next to a residential neighborhood.”

Because of the bipartisan support of big tech industry and large-scale data centers, Marcille-Kerslake said she believes there will be an “explosion” in fracking and fossil fuel infrastructure due to the energy demands of data centers and AI, which will “take us backwards.”

“You feel a bit untethered knowing that the party that is supposedly on the side of the environment, the party that recognizes that climate change is an existential threat, is also the party, especially right here in Pennsylvania, that will be on board with these polluting projects,” Marcille-Kerslake said. “Our governor is pushing this and wooing the industry to come to Pennsylvania.”

Environmental advocates, including Marcille-Kerslake, are currently closely watching the movement of HB 502 in PA’s state legislature. The bill would take certain land-use authority from local governments and transfer it to a Reliable Energy Siting and Electric Transition board (RESET), which would have the power to issue a certificate accepting energy projects from zoning and other ordinances local governments are typically in control of.

Karen Feridun, a co-founder of the Better Path Coalition, helped pen an opposition letter to the bill’s RESET board. She is concerned that the board strips municipal governments of their authority over the siting of facilities. Though the board would have representation from the Department of Environmental Protection, it would also include Community and Economic Development, Labor and Industry, and PA Building and Construction Trades Council, which Feridun said are all somewhat “industry-friendly.”

“[This is] hugely disturbing because that’s where a lot of good organizing happens. That’s where you get to fight these things at the municipal level,” Feridun said. “To take that power away from communities to defend themselves and say that they don’t want something in their community is really bad.”

The bill has yet to be passed, but Feridun and fellow environmental advocates believe it may pass along with the state budget.

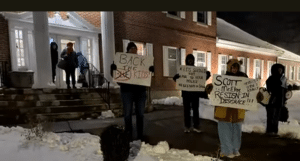

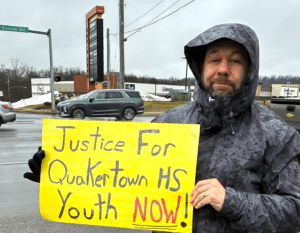

According to Data Center Watch, $64 billion of data center projects have been blocked or delayed by local opposition for reasons such as water straining, noise, higher utility bills and green space preservation. According to the report, voters in Warrenton, Virginia voted out all town council members who supported Amazon’s incoming data center in the November 2024 election. Additionally, while 93% of Americans agree that AI data centers are vital to the U.S., only 35% say they would vote “yes” to data center construction in their hometown.

READ: Why Your Electricity Bill Is So High and What Pennsylvania Is Doing About It

The data center in Falls would be connected to the electricity grid. Although the Falls data center would not be connected to a nearby natural gas power plant, the grid is powered by natural gas, and notably, only 4% of power generated in PA is renewable energy. Despite this, Amazon has said all of its operations, including its data centers, are now powered by renewable energy, which raises an eyebrow for Feridun.

“This idea that you’re connecting to the grid doesn’t mean you’re not connecting to fossil fuels, if you’re just doing it more indirectly, or nuclear or any other kind of dirty energy source. You’re just not doing it directly as having a power plant on site,” Feridun said. “So, when they talk about the stuff about how they’re going to be all green, it’s just nonsense.”

Good said Amazon’s goal of 100% renewable energy and other companies with similar goals give them an incentive to source as much as they can from clean energy, but with the exponential growth in data centers for the next 10 years, utilities and grid operators have been proposing delaying the closures of coal and fossil fuel power plants. In his article, Good reported that at least 17 fossil fuel generating units at seven power plants across the country have been delayed or are at risk of being delayed due to increasing electricity demand with data centers as a key concern.

“We’ve had coal and other gas-powered plants that had a set end date, and those have been pushed back to, in some cases, 10 years or more. In other cases, [it’s] just a couple of years, but we are seeing some that were scheduled to close in like 2028 that are now 2035 or 2040,” Good said.

Good sees the AI and data center boom as a “technological arms race” to develop AI models and deploy them as fast as possible.

“There’s a sense that we would want to have a strong AI infrastructure in order to compete with other countries in the world like China, so you’ll hear politicians talking about how it’s important for our national security, and we need to make sure we win the quote-unquote AI race,” Good said. “I’m not sure what the vision for winning that race is, what that would actually look like, and how that would benefit our society.”