This article originally appeared on Inside Climate News, a nonprofit, non-partisan news organization that covers climate, energy and the environment. Sign up for their newsletter here.

Two neighboring townships in a heavily fracked part of Pennsylvania are seeking federal and state funding for a public water system to replace private wells that have been contaminated for more than three years.

Freeport and Springhill townships in the southwest corner of the state have each recently used the contamination to declare a “disaster emergency” because of their long-running water problems. The declarations allow a municipality to apply for public funds to fix a problem.

The Greene County towns are believed to be the first in the state to use the emergency declaration in relation to drinking-water contamination, said Guy Hostutler, chairman of the Freeport Board of Supervisors, which published its statement in June. Neighboring Springhill issued its own disaster declaration in August.

Since fracking for natural gas began in Pennsylvania in the mid-2000s, some residents have complained that their water, if drawn from aquifers, has been contaminated with hazardous chemicals used in fracking. In those cases, residents are forced to rely on bottled or filtered water, or on “buffaloes”—large plastic tanks installed outside homes and periodically filled with clean water.

Critics of the gas industry blame the contamination on “frac-outs,” in which fracking fluid pumped underground at high pressure leaks from its borehole into aquifers or escapes from the surface. Such incidents have polluted some drinking water sources and delayed the construction of gas wells or pipelines.

In Freeport’s case, around 200 of its approximately 300 residents have experienced discolored and chemically contaminated water since June 2022, Hostutler said. That month, the gas company EQT experienced a “frac-out” as it was horizontally drilling a nearby well.

Since then, affected homeowners have been unable to use their wells and have relied instead on water from buffaloes or filtration. EQT has provided both while not acknowledging that it had anything to do with water conditions there, Public Source reported last year.

The well water has been tested by Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection, which determined in February that the water is not fit for human consumption. Freeport then approved the disaster declaration that allows it to seek public funding for a public water system.

“We filed it because we felt it was our best option to try to get funding to try to get a water line laid to the residents of the Freeport-Springhill area,” Hostutler said in an interview. “We’re a very small township and the rough estimate for the water line is between $21 and $25 million. We don’t have anything close to that, so we are going to need state funding as well as federal funding to get the water line laid.”

Hostutler backed away from the declaration’s claim that EQT was responsible for the contamination. The document said that “on or about June 19, 2022, a contamination event caused by actions of EQT has caused or threatens to cause injury, damage, and suffering to persons and property of Freeport Township.”

But in the interview, Hostutler said the contamination could have been caused by other parties, such as pipeline builders or operators of conventional gas wells. Township solicitor Grant Allison said the municipality is acknowledging the possibility but is not excluding EQT.

READ: Pennsylvania Fracking Company Surrenders Water Permits Over Concerns About Stream Flow

“There are other companies performing work in the area, and it would not be prudent for the Township to disqualify all other actors while there are still active investigations ongoing,” Allison wrote in an email. “The Township is not absolving EQT by any means.”

Allison said the disaster declaration is not connected to a pending class-action lawsuit by affected Freeport residents, accusing EQT of contaminating water and exposing residents to potentially harmful chemicals. The suit, filed in June 2024, states that Pennsylvania officials have reported some 400 cases of gas-industry impacts on underground water supplies since 2007.

Asked why it took three years for the town to issue its disaster declaration, Hostutler said it had to wait for the DEP to conclude that some private wells contained water unfit for human consumption. He declined to identify the contaminants found in the private well water, saying that information is part of the residents’ lawsuit.

Even if money is found for a public water system, it could be three or four years before it’s in place, Hostutler said.

EQT did not respond to two emails seeking comment. The Marcellus Shale Coalition, a trade group for the gas industry, also did not respond.

The DEP investigated 24 cases in which Freeport residents claimed the industry contaminated their wells, but it found no evidence of such a link, said Neil Shader, a spokesman for the agency. Still, the DEP is now looking into more recent complaints, including one that the township’s water source for washing vehicles and other non-drinking purposes has been contaminated by unconventional gas drilling.

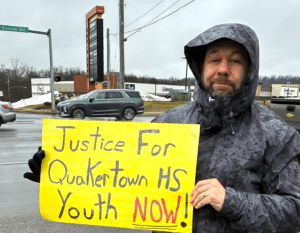

The Center for Coalfield Justice, an advocacy group for workers in the coal and gas industries and nearby residents in southwest Pennsylvania, has provided drinking water for some affected residents. It has also pressed EQT to pay for restoring water supplies that CCJ contends the company contaminated. But after the disaster declarations, the group fears EQT is hoping to avoid the cost.

“EQT is interested in letting taxpayers pay the cost of cleaning up their mess,” said CCJ’s executive director, Sarah Martik. “Since federal and state representatives have got involved, the conversation has gone from holding EQT accountable to providing public water. Now it’s, ‘Let’s get taxpayer dollars to pay for that.’”

Residents fear additional contamination, Martik added.

“Clearly there is a pathway for the fracking fluids to be engaging in the aquifer,” she said. “People were saying, ‘As soon as I bathed in this water, I got rashes’; ‘my tomato plants died after I watered with this’; ‘my dogs won’t go anywhere near this water.’ People just don’t necessarily have clean water.”

Now that the townships have issued their disaster declarations, some state lawmakers are pledging to help find public funding to fix the water problems. They include Rep. Bud Cook, a Republican who urged Freeport officials to approach PennVest, a financing authority that offers low-cost loans for municipal infrastructure projects that address water and other public needs.

“I am saddened to hear about the ongoing water-quality issues in Freeport Township, and the recent declaration of a Disaster Emergency,” Cook wrote to the town’s supervisors in July. “Please know that my office is here as a resource throughout the process.”

The office of U.S. Rep. Guy Reschenthaler, a Republican who represents the area, did not respond to questions about whether he supports finding federal dollars to help pay for public water in the townships.