A report released Monday shows that corporate investors eager to cash in on the nation’s profit-driven housing market have devoured tens of thousands of individual homes and residences in largely Black and Hispanic neighborhoods in Philadelphia, raising concerns about increased evictions, higher rents, and reduced homeownership.

The timeline for Corporate Investors in Single Family Homes in Philadelphia, compiled by Emily Dowdall, President of Policy Solutions at the Reinvestment Fund, the Fund’s Policy Analyst Michelle Schmitt, and Katharine Nelson, PhD and her team at Rutgers University, is buffeted by two massive 21st century calamities. She and her team began collecting purchase data for single-family and small multi-unit homes – up to four units each – during 2017, less than a decade after the nation’s housing market was rocked by the great recession. During the aftermath of the stock market crash, massive taxpayer bailouts went to the mortgage lenders who survived the collapse.

Their data collection continued through 2022 – at which point the Covid-19 pandemic had already claimed a million U.S. lives, triggered rampant inflation, never seen before unemployment rates, and a titanic low-income housing crisis.

In those six years studied, Nelson found that purchases of single-family homes and small multi-family dwellings were no longer the sole domain of single families.

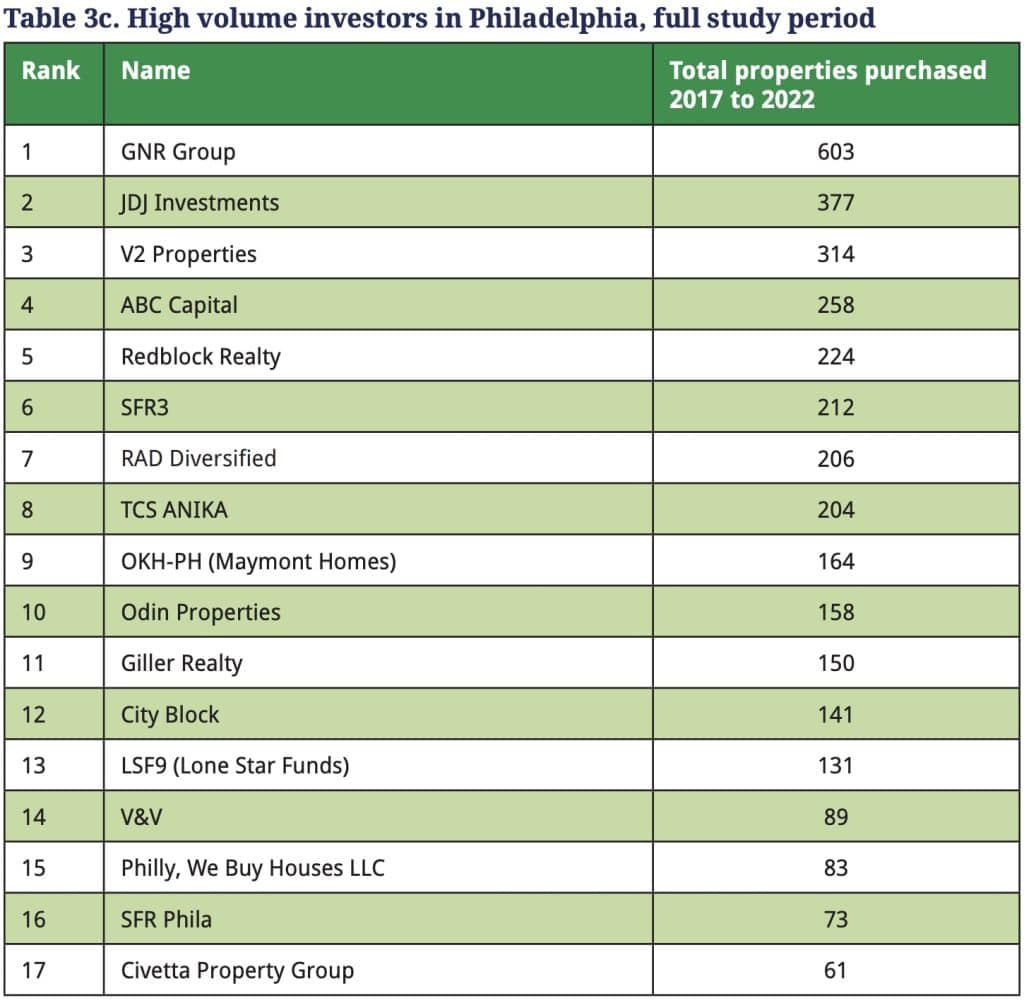

The Rutgers group found that between 2017 and 2022 approximately 25 percent of homes were purchased by corporations – most of which purchased fewer than 100 properties in the study period. Thirteen corporations purchased more than 100 and eight investor groups purchased more than 200 homes in the six-year period. According to the study, those units were “in the parts of the city where prices are lowest, and which are predominantly home to Black and Hispanic residents.”

Widespread corporate ownership of rental properties isn’t new. At the turn of the 20th century – when U.S. income inequality was at its second worst – second worst to now – corporations from textile manufacturers to coal mines to railroads engaged in the lucrative practice of building housing and leasing it to their workers.

It wasn’t until labor union movements of the late 19th century and early 20th century federal labor standards reforms, including the New Deal, that lower income American wealth grew and individuals and families could purchase the homes that corporations had for a century been leasing at a remarkable profit.

When the subprime mortgage bubble burst, crashing Wall Street in 2008, and $3.2 trillion was lost by U.S. banks and brokers, investors moved from owning the mortgages to purchasing the properties outright.

Rick Smith, lifelong member of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters and host of the Rick Smith Show – a TV and radio program about the working class – explained, “They sold a bunch of people, a bunch of houses they couldn’t afford. They were selling all this stuff [mortgages] as gambling tools on Wall Street, which created this perfect storm of horrible. And when the economy took a downturn, the bubble went boom. Hundreds of thousands of people lost their homes.”

And when they did, Smith concluded, “Investors clawed back the asset when it was sold at sheriff’s sales. Or when homeowners get desperate to sell. You see the signs everywhere, cash for your home.”

Once Nelson identified who the institutional investors – their term for corporate landlords on a large scale – in Philadelphia were, she and her colleagues set about evaluating the impact of their practice. “The second thing we wanted to understand was, okay, there’s a lot of research out there that shows that these really large private equity companies have some deleterious impacts on housing markets.”

Including inflation.

“They’ve been associated with growth in prices, which – to some people may say ‘good’ – to many others, it is not,” said Nelson.

Not to mention lost housing.

“They’re associated with higher eviction rates. They’re associated with rent increases, price increases. So, we wanted to see, with this kind of different local regional animal, if the same sort of things held,” she said.

And they did.

“We proceeded to, by size, look at the big ones that we’d been able to identify. We looked at what they were doing in the marketplace,” said Nelson. “Were they landlords or were they flipping [the property for resale] or what were they doing? We found out they’re primarily landlords.”

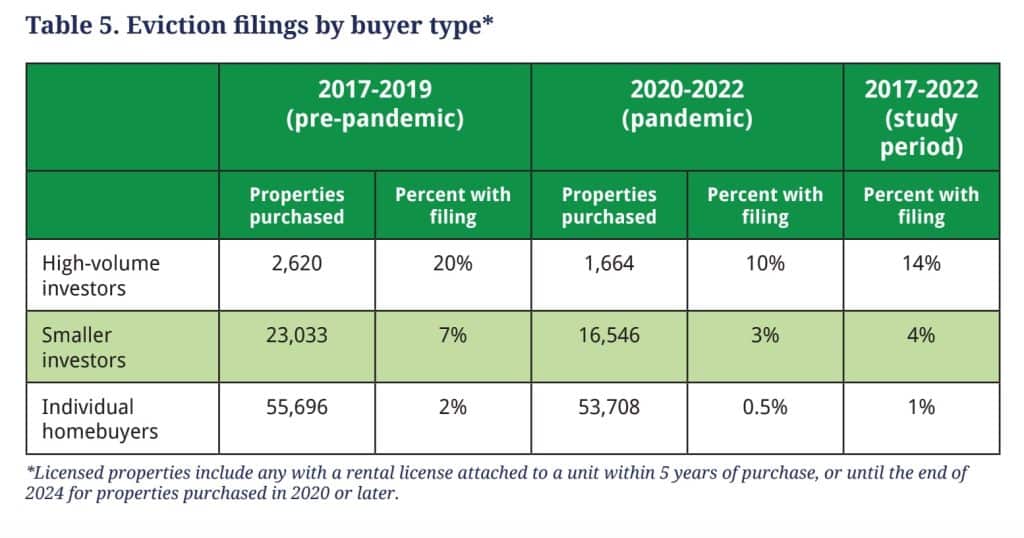

Nelson then wanted to know what kind of landlords. “We looked at eviction rates and we found that those big ones have pretty high rates of eviction. It’s 14 percent compared to a much lower 4 percent among smaller buyers that use company names, LLCs, and that sort of thing.”

And the team found that the small mom and pop, non-corporate landlords had an even lower overall eviction rate of just 1 percent.

There were other impacts Nelson studied. “Then we looked at complaints, code violations. We found that those were also higher for investors.” For both corporate investor types, citations for needed work was double that of small property owners.

Nelson said that most Philadelphians have never heard of the top 10 property owners in the city. And while most of these private equity companies are regional – having grown organically over the years, four of the top ten are from away.

Gil Brenner, the CEO of Property Management for GNR – the largest property management organization in Nelson’s study – sat down with Bucks County Beacon and explained how they see their role in the community. He said that in Philadelphia there consists of anywhere from 1,300 to 1,400 rental properties.

Brenner explained that their funding comes from a wide range of investors, coupled together. “We work like most real estate developers who raise funds under LLCs. Those investors will profit from our management.”

And while, in the past they had purchased foreclosure properties – as mentioned in Nelson’s study – that practice has all but dried up. Brenner explained that shortly before Rutgers concluded their study – and likely because of the pandemic – property auctions became global.

“We, as a company have, in the past, been buying from sheriff’s sales. Once they put them online, people could sit in China and India. When they did that change, I wouldn’t categorize us any longer as sheriff sales buyers. We buy on the market now.”

Currently, in Pennsylvania, there’s no way of telling how many property purchases made that way. Matt Heckel, Press Secretary at the Pennsylvania Department of State, confirmed in a statement to the Bucks County Beacon that the commonwealth does not track international purchases. “The sale and purchase of real estate is a contractual transaction over which the Real Estate Commission has no jurisdiction, and the Commission does not track real estate sellers or buyers.”

Additionally, the only time the nationality matters in a real estate transaction is when the seller gets paid, and then by the federal government – when 15 percent of the sales price is withheld for tax purposes.

As for being part of a statistical deficiency, whether that be evictions or code enforcement issues, Brenner stated emphatically that the increased numbers for large property owners is less about his company than the group in general. “We are very professional property managers. Mostly starting with the construction phase.”

Brenner says they specialize in purchasing blighted properties and rehabbing them for residency. “Ninety percent of them were shells – the worst you could find. We gutted them and renovated them.”

And evictions? “I can only speak about our company, but I promise you our eviction rate is lower, especially with our section 8 tenants. We are all passionate about the work we do, the people we rent to.”

Brenner referred to the U.S. Housing and Urban Development low-income housing subsidy program. “Ninety-five percent of our Philadelphia [properties] are HUD housing choice,” he said, where, he added, “Seventy-five percent of the rent is paid by the government, and 25 percent comes from the tenant.”

Historically, those rental units are a very safe bet. And when times are tough for his tenants to meet their share of the obligation, his staff helps where they can. “We care about people having a good housing experience. At the end of the day, we try our very best to help them find additional funding sources.”

What’s plaguing GNR right now, according to their CEO of property management, isn’t eviction rates or codes enforcement, “Right now in the city, there’s a vacancy problem – of all property types.” Brenner would like Philly’s low-income renters to know, “I have vacancies right now to offer to section 8 tenants.”

When asked if businesses like his might lower rents in order to increase occupancy, Brenner replied, “I think the market will correct itself. With interest rates holding, people will likely build fewer units.”

Keeping the market tight rather than lowering the cost on rentals may do nothing to address the overall issue of evictions or corporate ownership in Philadelphia, but Nelson’s study does provide recommendations for lawmakers going forward.

The study’s Policy and Regulatory Recommendations include, “investor transparency and accountability, improving public data, and enabling individuals and nonprofits to better compete with investors.”

Nelson explained the need for these changes, “I think the challenge is, when a larger apartment building or something like that is purchased – it’s very clear, the sort of size of the purchase – that is in the investment. But when the investor is purchasing individual properties at, you know, $40, $50, $60,000 each, sometimes scattered all across the city, it becomes harder to track.”

Nelson concluded, “That’s part of the challenge: the anonymity of these companies. Not only are they buying individual properties scattered in different areas of the city, they’re often doing so with different legal names. So, it makes it quite difficult for the city to know who they are and what they’re doing, let alone figure out how to regulate.”