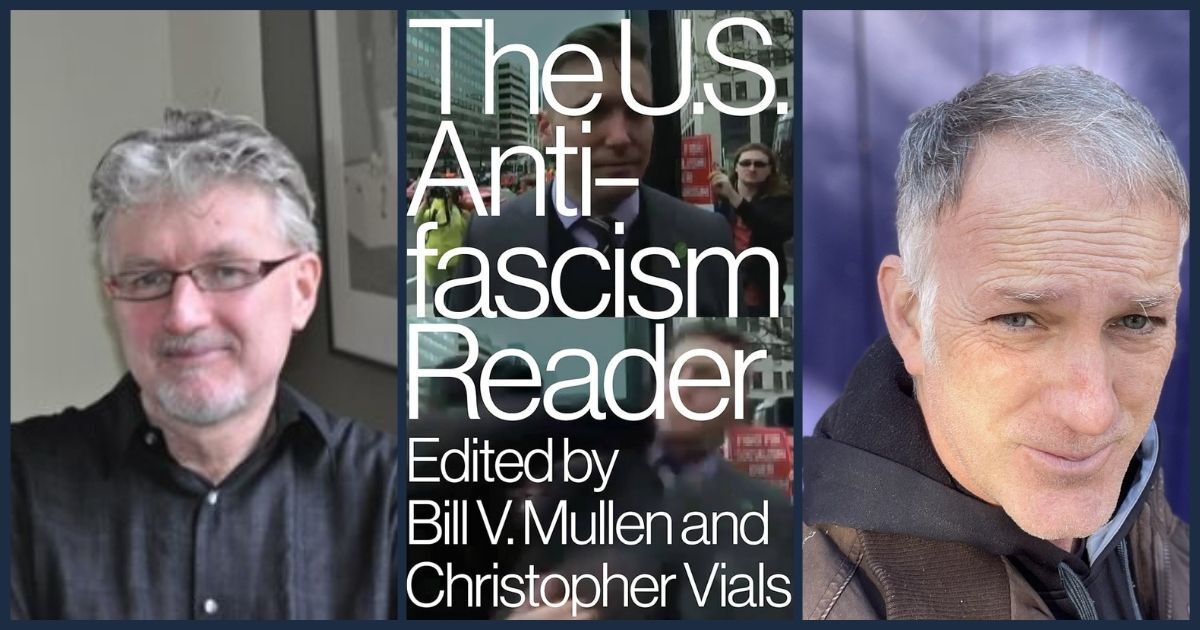

On this week’s episode of The Signal I welcome two guests: Bill V. Mullen, Professor of English and American Studies at Purdue University and Christopher Vials, an Associate Professor of English at the University of Connecticut, where he also serves as Director of American Studies. Together they co-edited the book The U.S. Anti-Fascism Reader. Today we talk about their book, the history of fascism and anti-fascism in America, and lessons we can learn to help us navigate through this moment where President Trump has just designated anti-fascism as domestic terrorism and on Tuesday told top military generals and admirals that the country faces an enemy from within (namely his political opponents) and that US cities should become training grounds for the military.

Listen on Apple, Spotify, Podbean, and iheart

TRANSCRIPT:

To start off, can you describe when and how you both decided to begin to research and ultimately edit The U.S. Anti-Fascism Reader, which was published in January 2020? And maybe Bill, if you could start off.

Bill: Would it be okay if Chris started? I say that because I think in some ways he was the initiator of this. I want to be fair about that.

Chris: I think both Bill and I had a longer term interest in anti-fascism. And this was in 2020 that we finally got out that, we were mostly writing and compiling it during Trump’s first term. And the obvious thing, you know, both of, again, I had published a book in 2014 during Obama on the history of anti-fascism in the U.S., but there was certainly a renewed interest with the rise of Donald Trump and the idea that authoritarianism could happen here. In both of our research, I think in different ways, we had uncovered bits and pieces of kind left-wing writing, really dating back to the 20s, that were interesting and revealing for activists later on, fighting fascism in their own country. And really it was kind of about the authoritarian far right kind of more broadly. But there were a lot of lessons to be learned from that. And it felt like tha tAmericans needed to know that they do have a history that kind of even goes under the name of anti-fascism, really dating back to the 20s, that long predates the quote unquote Antifa movement, which was much later in Europe in the late 80s, 90s, and then even later so here.

Bill: The only thing I would add to that is Chris and I also kind of started thinking about what became this book when we met as organizers around 2017 and started with some other people, this group called the Campus Antifascist Network. This was in the spring of 2017 after Trump was inaugurated. If you remember that moment, the far right people, like Richard Spencer were working really hard to get themselves onto college campuses to recruit. We started this network with the hopes that individual campus chapters could help push back on this so that if Richard Spencer wanted to come speak at your campus, you would organize an event against that happening. I have to say it was kind of slow going until Charlottesville happened. And then suddenly, you know, we had an enormous influx of people interested in trying to help us build this. We still actually have a website out there. And we ended up with like 15 chapters, which was a modest amount. But in some of the cases, like at Chris’s campus and at University of Michigan, people put up pretty significant protest when far-right figures came to speak. So to me, that’s another lineage of this project.

We’ve seen that locally in Pennsylvania. The University of Pennsylvania professor Amy Wax got into a lot of hot water because she had invited white nationalist and eugenics cheerleader Jarrett Taylor into the classroom, not just as a speaking event. And we’ve also seen Penn State invite the Proud Boys onto their campus. So that’s something that’s obviously been front and center all over the country, this debate over campus free speech, what that means and who that includes. But let’s get back to the topic of fascism. I was wondering if you could just briefly discuss the birth of fascism in Italy. What made Mussolini’s rhetoric and the Italian state uniquely fascist?

Chris: Well, keeping in mind, and that’s great that you begin with Italy, because when people say fascism, first of all, they are always thinking of Germany and the Holocaust, and for good reason. But Mussolini is the one who invented it. He comes to power in 1922, a full 11 years before Hitler does. Hitler models his revolution on Mussolini. You know, it really does start out, keep in mind, like before he seized power, there was all of these little January 6’s at the state level all over the country, like state houses were being taken over by and being invaded by fascist mobs and left-wing politicians thrown out. There was a coalition between landlords and the more modern fascists to destroy the left. So it really began as a campaign after World War I, some by World War I veterans, many of them middle class, to really just destroy left-wing organizations in the response to the Left.

What made it unique, I think, in a nutshell in Italian fascism was that it was distinctly authoritarian around a kind of a modern dictator. But it was this project of national renewal, you know, bringing back a great Italy that had never existed before. But with, a lot of traditional hierarchies intact. It was totally in line with capitalism, although it didn’t emphasize rhetorically with capitalism. In fact, much like in Nazi Germany, the class politics of Italian fascism were all over the place, you know, took bits from left and right, and seemed to have kind of an anti-Bourgeois ethos. But, you know, for the first 12 or so years of Mussolini’s regime, up until 1935, they actually reduced the size of the government, which is what you don’t usually associate with fascism as a percentage of GDP. There was less state expenditure, they actually reduced the size of government because they privatized a lot of stuff. So it was a rhetoric of kind of populism with class politics all over the place that really served the traditional elites, particularly capitalism, quite well. And its main enemy in Italy was not even the Jews for the first, you know, 12 or so years of it. It was really the political left. And a sense of victimization at the hands of the left.

And Bill, did you have anything to add to that?

Bill: We included in our book a piece about Italian fascism, particularly in relationship to its invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. And I wanted to say something just quickly about that. For Black Americans, the invasion of Ethiopia was the beginning of fascism. What they felt was that that was an attack on Black people. And one of the perspectives we try to raise up in our book is the relationship between Italian and European colonialism and the emergence of fascism. So just to take one example, there’s a man named Italo Balbo, who was a big muck-a-muck in Mussolini’s Air Force. But prior to being deployed in domestic fascism, he was stationed in North Africa overseeing what were called the protectorates in Ethiopia and Libya. In those places, the Italians did things like build internment camps and burn protesters. And this was kind of in the lead up to what became fascism in Italy in the late 1930s. And so that was a perspective we were trying to bring forward was what are some of the seeds and roots of fascism that we don’t always consider? So I’ll just add that to Chris’s really good description of especially what happened within Italy in that period.

I think it shouldn’t be lost on people as well that Mussolini had a lot of fanboys in the United States, in business, in the media, in Hollywood. His fascist movement appealed to a pretty broad swath of the American population. Isn’t that right?

Chris: Italian American communities, unfortunately, you know, quite a lot in the 1920s. And even some who otherwise voted New Deal and Democrat, it was just, you know, it was a maligned immigrant population for Italian men, a lot of Italian-American men in particular. Mussolini seemed like a kind of redemption. And yeah, the business press saw him and that was one of the pieces that we have in our book – the business press in the Wall Street Journal said he was basically management.

He was like basically putting the Italian state back on track again. He was like, it was like a receivership, under bankruptcy. And then it would kind of melt away, presumably. But yeah, and also like Bill said, to just keep in mind with this regime lasts a long time. In 1935, when after they invaded Ethiopia, their whole character changes. And also keep in mind, once they defeat their enemies at home, that violence has nowhere to go but outwards.

And that’s exactly what happened in Italy. They destroy the left at home and then they start really looking abroad to how can we carry that violence further into a colonial project. The regime gets much more explicitly racist and antisemitic after that invasion in 1935 too. And then race becomes much more central to its rhetoric.

Bill: Yeah, it’s amazing when you look at American magazines like Fortune and the Wall Street Journal in the 1920s. Mussolini was considered a capitalist hero by the American elites, somebody who was efficient. And part of that was the fascist attack on trade unions. American bosses were no more friendly to trade unions than Italians.

And they really saw him as an example of how you could defeat the labor movement. And it’s worth remembering that after 1917 with the Russian revolution, the trade union movement gets really militant in places like Italy and Germany, and particularly in Germany, there’s a kind of revolution that doesn’t happen in the early 1920s, led by trade unions and socialists. And so that defeat of socialism in Europe was really kind of a model in many ways, for the “Red Scare” panics that were happening in America. And so I think we could talk more about how as you move across the 20s and the 30s, sort of ruling class perspective, anti-communism in the United States, also give rise to a stronger far right within the U.S. that ends up supporting Mussolini and Hitler. So it’s an interesting, toxic cocktail, I guess, of things.

And so, we were talking about how fascism, its roots are being planted in the U.S. thanks to, what’s happening in Italy and Germany, but there’s also an anti-fascist reaction in the United States and an anti-fascism tradition, if you will. Can you talk about where, how that starts?

Chris: Well, it starts in those same Italian American communities in the 20s. In fact, there was some violence between fascists and anti-fascists, particularly in New York City in the 20s. So there was left-wing immigrants amongst the Italian American working class population. And so you were already starting to have these street fights in American cities back then. But it really takes off outside of Italian America in the early 1930s after Hitler takes power, then it becomes clear to most people that this is not just some kind of Italian problem, that this is going to be a world problem. And it’s scary because the country just fought a big war against Germany. They are a major industrial power and fascism seems to really kind of start to be taking off quite a lot then. And then that’s with, or almost simultaneous with the Chinese invasion of Manchuria and that starts to grow in 1937 with the full scale invasion of China. I think really with the rise of Adolf Hitler to power in January 1933, that’s when you start to see it. Americans going, OK, well, wow, this could actually happen here, too.

Bill: I’ll just add, go back to my Ethiopia example. We have a couple pieces written by people like W.E.B. Du Bois, by the middle of the 19th, Du Bois actually goes to Germany. People don’t even know this about him. And he rides around on a train in like 1934. And he’s like, what’s going on here? And he starts writing articles in the black press, like the crisis. Hey, people pay attention. Some really bad things are happening in Germany.

And so in 1935, when the Italian invasion happens, there’s this massive campaign called Hands Off Ethiopia. And the Black community in United States is becoming anti-fascist. Like they understand what’s up. And during World War II, there’s this interesting campaign we write about called the Double Victory Campaign, which started in the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper, which is a Black paper. And the argument was, you know, hands off fascism abroad, hands off racism at home. And they were responding to these Southern Dixiecrats, who constantly voted down anti-lynching legislation. Some of them were open admirers of Hitler. And these were Democrats. We remember at the time the Democratic Party was kind of the racist party until it was kind of flipped over completely. So this is a really interesting dynamic too, to another layer of anti-fascism that survives well into the 1960s when we talk about the Black Panther Party and how they become really like the epicenter of an anti-fascist movement in the late 1960s. I think one of the nice things about our book is that we’re just drawing out these currents and trying to tie them together to remind people it’s a pretty broad, vigorous tradition of anti-fascism when you start to pull back the carpet.

Could you talk a little bit about the American League Against War and Fascism and explain to listeners who they were?

Chris: So this starts in 1933 and it’s basically a, it’s a large kind of umbrella organization for all kinds of anti-fascist groups. And it’s really is kind of spearheaded by the Communist Party USA, but most of the organizations that are part of it are not communist or even socialist. You have even organizations like the early NAACP and the urban league in there and the ACLU is kind of participating…the overall kind of scope of it is very, very, very broad. So it unites all of these kind of left and liberal organizations. There’s even some kind of, by the late thirties, there’s some even cooperation with the Roosevelt administration. And they’re kind of organizing marches, demonstrations, a lot of kind of press.

So anytime that the Hitler or Mussolini government does something outrageous, they kind of are out protesting and trying to associate fascism, the word fascism, with negativity. And keep in mind, as we were talking about earlier, and you mentioned too, fascism was not always a negative word in the United States. So what this kind of massive umbrella organization kind of does is help to make fascism kind of a dirty word. And also to remind people it’s not just a foreign thing, it could happen here. And it’s been happening here in various guises with lynching and racial violence in the United States. We have the nucleus for it already here. And all it takes is a little push and a shove and the U.S. could go in that direction too. So they never, they were always kind of fighting, you know, and trying to raise awareness about Hitler and Mussolini and also Imperial Japan, but also at the same time being very mindful that in things like racial violence at home and anti-Semitism in the United States, that we also have great fascist potential here too, and that liberal institutions are not necessarily going to save us.

One of the essays that you actually included in your collection was a warning by Henry Wallace, Roosevelt’s vice president, called The Danger of American Fascism, which he had published in the New York Times Magazine in 1944. I almost find it shocking that someone like that, a vice president of the United States, would be so outspoken and pretty quite eloquent about his understanding about the gravity of the situation that the United States faces. I feel like we’re desperately needing something like that right now.

Chris: Yeah, and Wallace was FDR’s vice president from 1940 to 44, very progressive. And what’s striking about that piece is that, you know, he’s basically saying that fascism is what happens when big business decides that it doesn’t need democracy anymore and democracy is a pain. So we will go towards kind of a stronger, more authoritarian methods. That idea was really mainstream in the 30s and 40s.

I mean, even Truman, President Truman later on had said various things kind of like that in some of his speeches when he was running for president. So even in 1948, that was pretty mainstream at the time.

Bill: Yeah, one other thing I would say about that period. The Progressive Party wants to be to the left of the Democratic Party. And the House of American Activities Committee, its precursor, was formed around 1938. And there was already the specter of an internal repressive mechanism developing in the United States was pretty clear before the war even ended. And obviously, once the war ends we get full blown McCarthyism. So there were reasons to be concerned that something like the state repression of political difference was a real possibility. And of course it became hegemonic during the Cold War. So I think Chris is right that savvy, smart left liberals like Wallace understood that all was not necessarily well in the Republic, even though the U.S. was trumpeting itself as, as it always did as the paragon of democracy and the exact opposite of fascism. I mean, one of the things Chris and I talk about is we have this thing called American Exceptionalism. It can’t happen here. Well, why do we know that? Well, because we’re just, you know, the Soviets and the Germans are the fascists – we are the beacons of freedom.

But there’s always contradictions within American liberalism that we’ve seen play out recently. People are very frustrated that Democratic Party doesn’t seem to really stand strong enough against Donald Trump. I think a lot of people wonder what is the value of liberalism? We’ve always been told it’s meant to be a break on fascism, a break on authoritarianism. And now we see many times, I believe that as many, I think that the vote to commemorate Charlie Kirk’s murder was pretty much bipartisan and unanimous. This is really interesting. This is pretty much of an open bigot who’s now being lionized by the liberal Party of the United States. So I think Wallace wouldn’t have been shocked, but he probably would have had to write another essay about, another warning essay about what this could mean.

The whole idea about American Exceptionalism and that it can’t happen here also kind of ignores the fact that we helped it happen abroad. For example, September 11, 1973, the CIA helped overthrow Chilean democracy and install dictator General Pinochet, Augusto Pinochet. One question I did have about this though, and I was hoping for you to clarify. Is the Pinochet regime a fascist regime? Because he employed death squads. He had the DINQ, the secret police. They hunted, tortured, disappeared, and murdered leftists, which is anyone to the left of this murderous regime. And this regime even serves as an inspiration to the modern right in the United States as we’ve seen Proud Boys wear shirts, lionizing Pinochet or the practice of dropping leftists out of helicopters into the ocean. Is Pinochet’s regime actually, would you consider that fascist or is it just a bloody authoritarian military dictatorship?

Bill: Debate still going on to this day. You know, I think Chris and I talk about fascism to some extent as a bit of a spectrum sometimes politically. There are states that use fascist tactics and strategies, but have not necessarily become full-blown fascist states. And I would put Pinochet in that category of a state that used repression, criminalized dissent, used state violence, again, came into power as a smashing of a left-wing regime, which is a very characteristic pattern of fascism. It fits there. But I would argue if the metric is the Italian and German model, it doesn’t quite achieve that level of efficiency, as it were. But I’m also one who argues, to go back to the spectrum, that we’d have to put other regimes in the spectrum conversation sometimes too. We’re living in a moment when Bolsonaro was running Brazil, was using a lot of tactics and strategies that clearly drew from a fascist tradition of governance. Fortunately, he was voted out of office. Our book is trying to, I think, open up questions like you’re asking, but to remind us that anti-fascists theorizing about fascism has oftentimes raised these kinds of points themselves. And that’s why we need to read them.

Chris: Yeah, no, it’s a good question. And this question is it fascist or not? And having scholars talk about it drives everybody else insane. Sometimes you ask a lot of people if you look at the Latin American reactions of this, it’s very common to call it fascism. And I’m not going to argue with somebody that got tortured and say, OK, well, technically that’s not fascism. But, you know, just keeping in mind that authoritarianism takes many, many forms, and fascism, I kind of tend to write and most write as a specific form of right-wing authoritarianism. I think we could say, I would say probably Pinochet’s regime is close enough, it’s authoritarian, there’s a narrative of national renewal, there’s a racialization of a national minority oftentimes, fanatical anti-communism, a warrior ethos at the center of it, and an ambivalence sometimes about capitalism, and I think that last part is why some folks are kind of a little bit on the fence about Pinochet because fascism is not typically just simply traditional elites restoring their own rule. It tends to be this kind of middle class movement or some kind of militarist far right movement that’s in league with capitalism and it forms an alliance with capitalism, but it’s not necessarily capitalism itself. But again, if you’re tortured by this regime and murdered by it or as a leftist or thrown out of a helicopter, which a lot of that was Argentina too, then I’m not going to argue with somebody that says, that’s fascism. It’s close enough.

I think right now we’re seeing a similar kind of debate and some might say hair splitting about what this second Trump term actually means, what this moment that we’re living through right now is. Can you talk about the rhetoric, the right wing social movement organizing, and even the remaking and weaponization of the state that we’re seeing the second Trump administration employ? Does it qualify as fascism or a movement towards fascism in the United States?

Bill: In our book, Chris and I say about the first Trump term that he used a fascist grammar, but he didn’t have a fascist state. One thing I’ve always said is what if January 6th had started his term rather than ended it? Well, January 6th in a way started his second term because the first thing he did was pardon a bunch of people, many of whom were open fascists. Now that is more than dog whistling to the far right, that is inviting the far right into the regime. My interpretation is that the Trump state is actually absorbing a lot of the tactics, strategies, and ideas that have percolated up from the far right for the last 20 or 30 years. So for example, the ICE-ification of the streets is really the state’s version of the Proud Boys. And I read an interview with the leader of the Proud Boys a couple of weeks ago. And the New York Times reporter said, why are you guys so quiet these days? He says, what have we got to be upset about? The things that we were doing five years ago are now mainstream. Now I think that’s actually a kind of subtle insight into the moment that we’re living through right now. The other thing I would say is clearly the demonization of racial minorities, the attacks on Muslims and immigrants, the attacks on organized labor. He stripped 500,000 federal employees of their union rights right away. These are all classic right-wing authoritarian fascist tactics and strategies. And so I think the jury is out on whether or not this regime can continue to move in the direction it clearly seeks to move.

I will say one more thing. The new executive order on domestic terrorism is so broadly configured that I would say half to three-quarters of Americans might end up falling within its purview. Things like you are opposed to traditional American values of like the family. Well, good Lord. If that executive order were to be implemented, we could see a rest on a scale that we’ve never imagined in this country. I think this is an aspirational fascist regime. I think that the people like Stephen Miller and some of the architects of this state who are far more efficient than Donald Trump have a very clear fascist orientation and are testing the limits every single day, particularly in the courts, of how far they can push and how far they can go.

So I think it’s really naive for us not to consider the possibility that this state, which has by the way three and a half more years of rule, it’s only been in power for eight months. It feels like eight years. This has been a lightning strike of authoritarianism. And there is no bottom to it right now. There is no bottom to it. And so that’s my perspective on things. I’ll see what Chris thinks.

Chris: No, I agree with what you said very eloquently. The main thing I would add to that is that is a bit about the labels. That was part of the question. I reiterate that in what we said in the book, there’s a kind of a fascist intent here. But it’s just a matter of how much are they going to be able to implement. But the intent is a lot stronger and it has a lot less obstacles this time. And as Bill had said, there are open kind of fascists in the administration…people who like, you know, routinely saying things like the great replacement, they’re, they are, those are in the great replacement is basically this idea that international Jews are leading a conspiracy to replace whites with people of color. I mean, it’s a fascist idea. And it’s just right there, you know, it’s words like cultural Marxism, you know, other anti-semitic conspiracies about control and those folks are in the administration now, whether they’re going to be able to kind of fully implement that vision is really up to us…I’ll say too, I’ll know it’s interesting that one label that most people are, seem to be comfortable with this in this country is authoritarianism, which is again, a broader label than fascism, fascism’s particular type of authoritarianism. But even some of the political science writings on authoritarianism that go back 15 years, like that book, Competitive Authoritarianism, it’s checking all the boxes. There’s a 21st century version of authoritarianism where, for example, okay, they don’t, and this was written about 15 years ago, where they don’t necessarily lock up and kill all the journalists, but they’ll just take away their broadcasting licenses. So it’s like an authoritarianism-light. It’s maybe not as murderous, but they’ll game the political systems that one party can’t viably compete, or they’ll weaponize the law to say, doxing is illegal if you do it, but not if I do it, that kind of thing, which was in that executive order. You know, didn’t say directly it was illegal, but it was the kind of preamble to it. So all of those boxes for a slide into an authoritarianism in a distinctly 21st century way, it checks every box.

It’s undeniable.

So then let’s circle back to anti-fascism, Chris. Are there any common threads you’ve seen through history that reveal successful anti-fascist organizing strategies and tactics that communities can use today to help meet this moment that we find ourselves in?

Bill: Well, I’ll start. We make the point that one of the strongest obstacles to authoritarian and fascist states historically have been powerful left parties, which have often socialist, communist parties, for example, Trotskyist organizations, that have almost always been in the leadership of anti-fascist fighting. In America, the influence of such organizations is really tiny. We would probably have a more robust anti-fascist movement if socialist and communist ideas were more permissible and available, and not necessarily criminalized as they have been historically. And I think another element here would be the power of working class organization. To go back to Germany and Italy, it was the Italian and German Labor movement that was putting up one of the most robust fights against the emergence of fascism in the 1920s.

When those movements were effectively beheaded, it did a lot to open the door. I’m a member of the American Association of University Professors as is Chris. Our president, Todd Wolfson, who’s a really good guy, he’s pretty open about referring to Trump as a fascist. He’s trying to rally the troops. He’s trying to tell folks, if you are in education right now, you are at one of the front lines of a fascist takeover.

That’s why we’re talking so much about Trump’s policies towards Columbia and Harvard and the deportation of students, the criminalization of speech. My friend Tom Alter in Texas was just fired 10 days ago. He was speaking at a socialist conference that had nothing to do with the university. He was accused by his university president of inciting violence. This is the language that was used during the cold war under the Smith Act against Trotskyists and communists. If you were calling for socialism, you were inciting violence against the American state. So I guess my other point would be here, public sector workers, teachers, I feel like my union has a massive obligation right now to not just defend its members, but to do what Todd is saying, to say this is what authoritarianism looks like. We need to be explicit that we’re not just fighting for hanging onto our curriculum.

In most fascist states, the takeover of universities is another precondition for fascist hegemony. In our contemporary moment, Hungary would be a good place to look at. The way Orban has focused on the courts and the university system as a means of mainstreaming far-right thought. That’s exactly what’s happening here right now. So educator unions would be another front, I would argue, in this. And then the last thing would be the realm of law, which I’ve tried to write about recently. We need more movement lawyers. We need more William Kunstlers who’s not around anymore to defend the massive numbers of people who are being subject to authoritarian discipline right now. And I know that there are large numbers of organizations like Palestine Legal and the Center for Constitutional Rights and

the National Lawyers Guild, which are working triple time to try to keep up with these attacks. But we probably need an even broader…we need like a legal version of the Abraham Lincoln Brigades – lawyers to help save us from this internal catastrophe. So those are some of my thoughts on how we might fight back.

Chris: That was great. Everybody, think in this world will give you a slightly different answer on this question. One thing I agree with strongly and been in Bill’s response was the role of labor. Because that’s one of the, mean, first of all, sadly, think democracy has to deliver the goods for people to believe in it. You know, if we’ve been kind of since this rise of neoliberalism in the eighties, people’s standard of living in this country have been devastated. And it’s not getting any better right now either. You know, and unless, you know, the opposition can deliver the goods on some level, hope for democracy is not great. But one of the things on that note that was in the 30s a lot was that if you want to stop fascism, they were saying, at the time, join a union, which seems to make no sense on the surface of it. There makes a lot of sense.

And it’s also key to in mind that the United States in the 30s went in a more kind of left liberal direction, whereas Europe went to the right for the most part, which was that if what unions do, particular types of unions that are inclusive, you organize laterally on the basis of your position in the workplace across lines of race and gender, again, if it’s a good union, a progressive union, and you kind of identify with people on the basis of your class and workplace position laterally, no matter who they are, rather than what fascism and far-right politics tries to do or white supremacists particularly, which is like trying to make you identify vertically on the basis of your race. I’m an Aryan, whether I’m working class, middle class, rich, we’re all united by this Aryanness or whiteness or whatever. But these organizations, and they can deliver the goods in your lifetime…like right now. You can negotiate a contract and be paid better. You know, it’s not abstract. So that kind of union stuff is, and again, a very kind of open, inclusive kind of unionism, I think is still absolutely critical to going forward. And we could talk more, like, you know, if we had more time about Popular Front versus United Front strategies and all that, and we’d probably have disagreements there. BuI think that’s unionsthat could deliver the goods in people’s lifetime, their participatory, give them a sense of belonging. And it really does start at a movement level. I don’t even think it starts at the level of a party, but a party is important.

One final question. Glenn Beck used to ask his guests, who’s your favorite founding father? But what I want to know is who’s your favorite anti-fascist? you have one, Chris and Bill?

Bill: That’s such a hard one.

I don’t know…I have so many, but I’ll just throw out Woody Guthrie just because I’m a guy who thinks that culture plays an important role in politics. And he was clearly one of the first to say “this guitar kills fascists,” that the artist has a role to play in organizing against fascism. The other person from that period I love is Paul Robeson, who basically said the same thing. He said the artist must take sides. And, you know, it’s really important that we have a tradition of actors and writers. Hemingway was an anti-fascist. It’s important that artists and cultural workers perceive themselves as part of the broad struggle because if Taylor Swift tomorrow announced she was an anti-fascist, wow, that would get people’s attention. And what I mean by that, to go back to Chris’s point, is that culture and popular culture are ways we tap into what mass numbers of people are thinking and feeling. So every time an artist steps forward and says, I’m an anti-fascist, I get chills. I think, OK, that’s a step forward.

Chris: Ditto.