A Medicare pilot program will allow private companies to use artificial intelligence to review older Americans’ requests for certain medical care — and will reward the companies when they deny it.

In January, the federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services will launch the Wasteful and Inappropriate Services Reduction (WISeR) Model to test AI-powered prior authorizations on certain health services for Medicare patients in six states: Arizona, New Jersey, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas and Washington. The program is scheduled to last through 2031.

The program effectively inserts one of private insurance’s most unpopular features — prior authorization — into traditional Medicare, the federal health insurance program for people 65 and older and those with certain disabilities. Prior authorization is the process by which patients and doctors must ask health insurers to approve medical procedures or drugs before proceeding.

Adults over 65 generally have two options for health insurance: traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage. Both types of Medicare are funded with public dollars, but Medicare Advantage plans are contracted through private insurance companies. Medicare Advantage plans tend to cost less out of pocket, but patients enrolled in them often must seek prior authorization for care.

AI-powered prior authorization in Medicaid Advantage and private insurance has attracted intense criticism, legislative action by state and federal lawmakers, federal investigations and class-action lawsuits. It’s been linked to bad health outcomes. Dozens of states have passed legislation in recent years to regulate the practice.

In June, the Trump administration even extracted a pledge from major health insurers to streamline and reduce prior authorization.

“Americans shouldn’t have to negotiate with their insurer to get the care they need,” U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. said in a June statement announcing the pledge. “Pitting patients and their doctors against massive companies was not good for anyone.”

AI-powered prior authorization in Medicaid Advantage and private insurance has attracted intense criticism, legislative action by state and federal lawmakers, federal investigations and class-action lawsuits. It’s been linked to bad health outcomes.

Four days after the pledge was announced, the administration rolled out the new WISeR program, scheduled to take effect in January. It will require prior authorizations only for certain services and prescriptions that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services has identified as “particularly vulnerable to fraud, waste, and abuse, or inappropriate use.” Those services include, among other things, knee arthroscopy for knee osteoarthritis, skin and tissue substitutes, certain nerve stimulation services and incontinence control devices.

The companies get paid based on how much money they save Medicare by denying approvals for “unnecessary or non-covered services,” CMS said in a statement unveiling the program.

The new program has alarmed many physicians and advocates in the affected states.

“In concept, it makes a lot of sense; you don’t want to pay for care that patients don’t need,” said Jeb Shepard, policy director for the Washington State Medical Association.

“But in practice, [prior authorization] has been hugely problematic because it essentially acts as a barrier. There are a lot of denials and lengthy appeals processes that pull physicians away from providing care to patients. They have to fight with insurance carriers to get their patients the care they believe is appropriate.”

CMS responded to Stateline’s questions by providing additional information about the program, but offered few details on what the agency would do to prevent delays or denials of care. It has said that final decisions on coverage denials will be made by “licensed clinicians, not machines.” In a bid to hold the companies accountable, CMS also incentivizes them for making determinations in a reasonable amount of time, and for making the right determinations according to Medicare rules, without needing appeals.

In the statement announcing the program, Abe Sutton, director of the CMS Innovation Center, said the “low-value services” targeted by WISeR “offer patients minimal benefit and, in some cases, can result in physical harm and psychological stress. They also increase patient costs while inflating health care spending.”

A vulnerable group

Dr. Bindu Nayak is an endocrinologist in Wenatchee, Washington, a city near the center of the state that bills itself as the “Apple Capital of the World.” She mainly treats patients with diabetes and estimates 30-40% of her patients have Medicare.

“Medicare recipients are a vulnerable group,” Nayak told Stateline. “The WISeR program puts more barriers up for them accessing care. And they may have to now deal with prior authorization when they never had to deal with it before.”

Nayak and other physicians worry the same problems with prior authorizations that they’ve seen with their Medicare Advantage patients will plague traditional Medicare patients. Nayak has employees on staff whose only role is to handle prior authorizations.

More than a quarter of physicians nationwide say prior authorization issues led to a serious problem for a patient in their care, including hospitalization or permanent damage, according to the most recent report from the American Medical Association.

And some patients are unfairly denied treatment. Private insurers have denied care for people with Medicare Advantage plans even though their prior authorization requests met Medicare’s requirements, according to an investigation from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services published in 2022. Investigators found 13% of prior authorization denials were for requests that should have been granted.

But supporters of the new model say something must be done to reduce costs. Medicare is the largest single purchaser of health care in the nation, with spending expected to double in the next decade, according to the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission, an independent federal agency. Medicare spent as much as $5.8 billion in 2022 on services with little or no benefit to patients.

Congress pushes back

In November, congressional representatives from Ohio, Washington and other states introduced a bill to repeal the WISeR model. It’s currently in committee.

“The [Trump] administration has publicly admitted prior authorization is harmful, yet it is moving forward with this misguided effort that would make seniors navigate more red tape to get the care they’re entitled to,” U.S. Rep. Suzan DelBene, a Washington Democrat and a co-sponsor of the bill, said in a November statement.

Physician and hospital groups in many of the affected states have backed the bill, which would halt the program at least temporarily. Shepard, whose medical association supports the bill, said that would give CMS time to get more stakeholder input and give physicians more time to prepare for extra administrative requirements.

“Conventional wisdom would dictate a program of this magnitude that has elicited so much concern from so many corners would at least be delayed while we work through some things,” Shepard said, “but there’s no indication that they’re going to back off this.”

Adding more prior authorization requirements for a new subset of Medicare patients will tack on extra administrative burdens for physicians, especially those in orthopedics, urology and neurology, fields that have a higher share of services that fall under the new rules.

“Prior authorization delays care and sometimes also denies care to patients who need it, and it increases the hassle factor for all physicians.” -Dr. Jayesh Shah, President of the Texas Medical Association

That increased administrative burden “will probably lead to a lot longer wait times for patients,” Nayak said. “It will be important for patients to realize that they may see more barriers in the form of denials, but they should continue to advocate for themselves.”

Dr. Jayesh Shah, president of the Texas Medical Association and a San Antonio-based wound care physician, said WISeR is a well-intentioned program, but that prior authorization hurts patients and physicians.

“Prior authorization delays care and sometimes also denies care to patients who need it, and it increases the hassle factor for all physicians,” he told Stateline.

Shah added that, on the flip side, he’s heard from a few physicians who welcome prior authorization. They’d rather get preapproval for a procedure than perform it and later have Medicare deny reimbursement if the procedure didn’t meet requirements, he said.

Prior authorization has been a bipartisan concern in Congress and statehouses around the country.

Last year, 10 states — Colorado, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Vermont, Virginia and Wyoming — passed laws regulating prior authorization, according to the American Medical Association. Legislatures in at least 18 states have addressed prior authorization so far this year, an analysis from health policy publication Health Affairs Forefront found. Bipartisan groups of lawmakers in more than a dozen states have passed laws regulating the use of AI in health care.

But the new effort in the U.S. House to repeal the WISeR program is sponsored by Democrats. Supporters worry it’s unlikely to gain much traction in the Republican-controlled Congress.

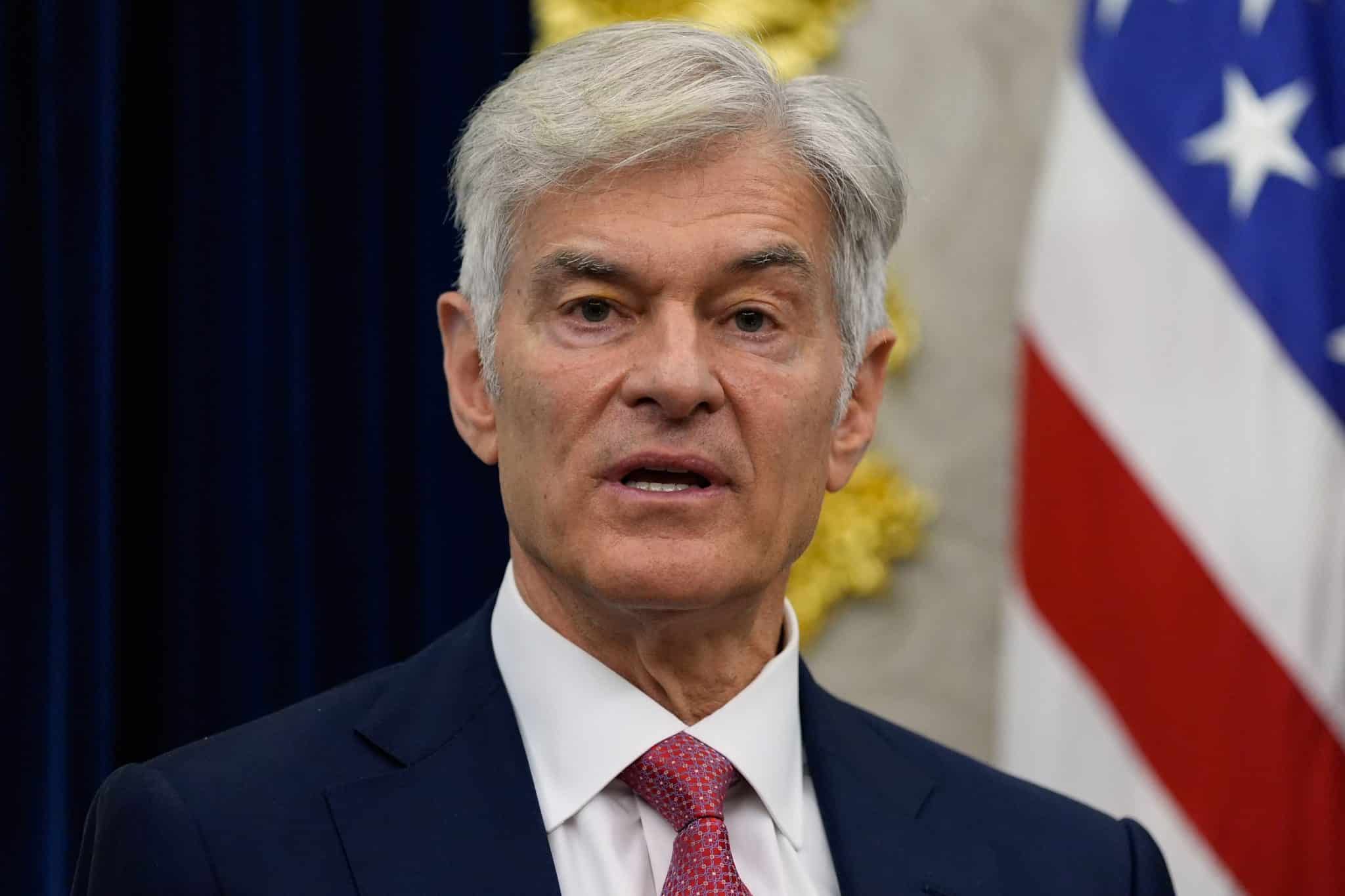

Shepard said his organization has talked with state and congressional representatives, met with the regional CMS office twice, and sent a letter to CMS Director Dr. Mehmet Oz.

“We’ve looked at all the levers and we’ve pulled most of them,” Shepard said. “We’re running out of levers to pull.”

Venture capital jumps in

CMS announced in November it has selected six private tech companies to pilot the AI programs.

Some of them are backed by venture capital funds that count larger insurance companies among their key investors.

For example, Oklahoma’s pilot will be run by Humata Health Inc., which is backed by investors that include Blue Venture Fund, the venture capital arm of Blue Cross Blue Shield companies, and Optum Ventures, a venture capital firm connected to UnitedHealth Group, the parent company of UnitedHealthcare. Innovaccer Inc., chosen to run Ohio’s program, counts health care giant Kaiser Permanente as an investor.

Nayak said she knows little about Virtix Health, the Arizona-based private company contracted by the feds to run Washington state’s pilot program.

“Virtix Health would have a financial incentive to deny claims,” Nayak said. “It begs the question, would there be any safeguards to prevent profit-driven denials of care?”

That financial incentive is a concern in Texas too.

“If, financially, the vendor is going to benefit by the denial, it could be a problem for our patients,” Shah said. He said that Oz, in a webinar presentation on the new program, assured physicians that their satisfaction and turnaround times would be metrics that Medicare would factor into the tech companies’ payments.

This article was originally published at Stateline. Stateline is part of States Newsroom, a nonprofit news network supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Stateline maintains editorial independence. Contact Editor Scott S. Greenberger for questions: info@stateline.org. Follow Stateline on Facebook, X and Bluesky.