This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Things have been looking up for the Democrats after this year’s elections.

In Virginia, where I live, the headline in November was the governor’s race, where former U.S. Rep. and CIA officer Abigail Spanberger beat Winsome Earl-Sears by a 15-point margin, an impressive victory considering that Kamala Harris took the state by 6 points in 2024.

In neighboring Tennessee, a special election in Tennessee’s 7th Congressional District on December 2 offered another window into the shifting electoral landscape. Republican Matt Van Epps beat Democrat Aftyn Behn 54-45 for the U.S. House seat vacated by retiring GOP Rep. Mark Green. Behn made the district competitive even though she was outspent 3 to 1 in a district Trump won by 22 points in 2024.

You might think that a win like Spanberger’s signals that Republicans stayed home. But analysis from Nate Cohn in the New York Times suggests something else is afoot. Although Spanberger’s win suggests an impressive Democratic turnout, he says, “it also implies that turnout alone didn’t explain the decisive victory.” Breaking down exit poll data, Cohn finds that 7% of Trump voters cast ballots for Spanberger.

Lily Franklin, heavily funded by the state Democratic party, beat Republican incumbent Chris Obenshain by a 6-point margin for a Virginia House of Delegates seat in the state’s House District 41, a district that Trump won by 4 points in 2024.

Cindy Green ran against well-funded Republican incumbent Israel O’Quinn in Virginia’s rural House District 44. As the first Democratic candidate running against O’Quinn since he was elected in 2011, Green performed similar to Harris, winning 23% of the vote.

Challenging Republican candidates like O’Quinn who rack up more than 77% of the vote is an uphill fight. It also means that Democrats need to win over Republican and Independent votes. Put another way, if 77% of your rural district is Republican, you can’t keep talking like a city Democrat to get Democrats elected.

Following the abandonment of Howard Dean’s “50 state strategy” and the resulting Democratic divestment from rural districts nationwide has entrenched an exclusivity in the party.

In Green’s case, talking to Republicans was something she was good at; she was born in nearby Kingsport, Tennessee, and has a sophisticated understanding of voter priorities. For example, at the United Mine Workers of America cookout in Castlewood, she won over Trump voters, something Spanberger could never do because she doesn’t relate to working class and rural people. And because of her support for Virginia’s “right to work” law—designed to handicap unions by stipulating that workers who receive union benefits don’t have to pay for them—the Virginia AFL-CIO refused to endorse her.

When Spanberger made a stop in Galax, Virginia, on January 17, a crowd of retired baby boomers cheered her as she talked about the need to raise teacher salaries. What she neglected to understand is that teaching in the public school system is among the better paying jobs in the area. In Carroll County, next to Galax, the starting salary in 2025 for public teachers is around $50,000-$55,000, while the median individual income is just above $30,000 (according to available data from 2023). Only 4-6% of jobs in southwest Virginia are in education, while manufacturing and service industries represent nearly 90% of the jobs, which have been steadily disappearing.

Reviewing the donor reports available through the Virginia Public Access Project for more than two dozen Democrats running in heavily Republican districts in Virginia, many of which are rural, it’s interesting to look at who is donating money to these underdog candidates. Most campaigns barely scrape together more than $10,000, with a few pulling in $20,000. As of December 4, these campaigns show small donations averaging around $500 coming in from county Democratic committees, Win Virginia, Virginia Democratic Women’s Caucus, Bluegrass PAC, Clean Virginia Fund and Lamont Bagby for Delegate fund. Most donations to rural Democrats come from a few private donors—ranging from $1,000-$3,000 each—and small donations of $100-250.

Green ran her campaign without receiving any funds from the state’s Democratic party. She raised $25,166, but only $2,500 came from local and regional Democrat organizations. These local groups, like county committees and congressional districts have to do their own fundraising. Even a $500 gift hits their bottom line. For example, sources report that some of these county committees have only around $300 in their bank accounts.

On the other hand, O’Quinn’s purse has been flush for the last 14 years. The O’Quinn campaign reportedly spent $719,566, outspending Green by nearly 29 times. His donors included familiar corporate names like Amazon, VA Auto Dealers Association, Data Center Coalition, Food City grocery chain, Sports Betting Alliance, Philip Morris International, Betting on Virginia Jobs, Comstock Hospitality Holdings, DoorDash, Ceasars Entertainment and United Co. (See O’Quinn’s fundraising and election history here for House District 44, 2023-2025, formerly HD 5, 2011-2021.)

If Green vs. O’Quinn is a measure of rural politics today, Green is “David” facing off against America’s corporate “Goliath.”

Following the abandonment of Howard Dean’s “50 state strategy” and the resulting Democratic divestment from rural districts nationwide has entrenched an exclusivity in the party. For a party that boasts about its “diversity,” that diversity is only skin deep if everyone is speaking the same branded language. It’s expected that messaging that works in affluent urban and suburban zip codes should automatically address the needs of voters in rural areas, small towns, tribal lands or poorer metro districts.

Virginia has the widest gap between the rich and the poor of any state. Northern Virginia—with its proximity to Washington, D.C.—is the richest region while the south and southwest is the poorest. A 2025 report from the University of Virginia’s Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service says that, “The rural-urban income gap is most obvious between Southwest and Northern Virginia: in Loudoun County [just outside Washington, D.C.] the median household income is four times greater than in Buchanan County [on Virginia’s southwest border with Kentucky]. No other state has a larger income gap between two counties.”

There’s also an historic demographic shift that Democratic leadership should pay attention to. Many rural districts across the nation are reversing historic population declines with population growth. Here in southwest Virginia, the UVA Weldon Cooper Center 2025 report points to a dramatic trend upward. Since 2020, we’re experiencing an influx of residents ages 25-44 at twice the rate of the national average. While the 2010’s saw southwest Virginia losing an annual 1,300 residents every year, since 2020, that number has reversed by 200%. Nowadays, southwest Virginia grows it’s population by 1,300 per year.

Despite the Democratic Party’s success at the top of the ticket, the experiences of Green and other rural candidates show the party’s rural-urban fissures continue to show through.

For all the positive news of her party’s success in November, Green cautions that there remains a disconnect between the top of the ticket and local candidates:

We had 100 candidates running in all House districts; we did not get support from the state party for the 27 rural candidates. And we are the ones on the ground in our communities who know what the community’s needs are. There was not collaboration between the top of the ticket with the rural candidates. However, because rural candidates ran, the top of the ticket was able to sweep [winning races for Governor, Lieutenant Governor and Attorney General]. We were their insurance policy because we we’re running in these rural districts and we were turning out people to vote Democratic. … And I think we saw that across the state, that the engagement from Democrats went up throughout the state, even in my district. I’m in an 80-20 Republican district, but you saw more Democrats turn out because they had somebody local they could get behind.

But for rural and small town voters, the perception that Roosevelt’s New Deal Democrats have been traded for corporatists in the state and national party leadership remains strong.

Green attributes this disconnect between the top of the ticket and local candidates not to one candidate like Spanberger, but to a systemic disconnect in the state party. She also describes barriers she faced just to become a Democratic candidate. She had to pay the party to get access to the party’s voter lists on the VAN [Voter Access Network], which costs between $750 and $1,000. She was also surprised to learn that once she gained the party’s endorsement, she had to give up some of her control over her own campaign. For example, party-endorsed campaigns in Virginia are required to use party-approved vendors like printers, marketers and consultants—contractors who are urban and centered near party headquarters.

These details may seem insignificant, but if a campaign is not allowed to source materials and consulting from their own districts, they end up paying city-prices and lose out on opportunities to support local businesses. An argument in favor of using party-approved businesses is that these vendors are unionized. But now that Democrat leadership in Virginia favors right-to-work laws, why would they care?

“I’ve been a Democrat my whole life,” says Green, “And so [when I decided to run and became the Democratic nominee] I thought, ‘I’m joining the team. Here we go!’ ” She pauses and shifts tone, “Oh, no, we’re not! You’re on your own! So from the party infrastructure, yes, that was very disappointing.”

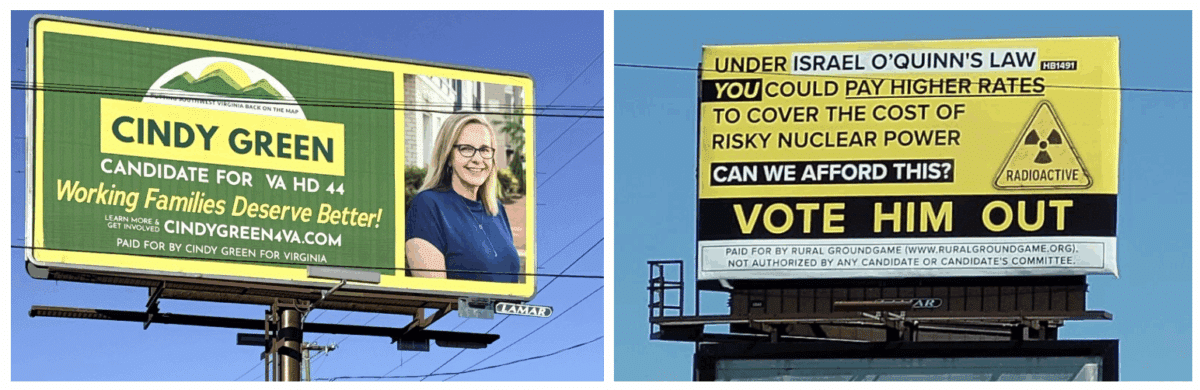

The communication break between party leadership, their consultants and local campaigns was heightened by the fact that party consultants posted billboards in Green’s district opposing a Republican-backed proposal in Wise County for a small modular reactor (a type of advanced and smaller scale nuclear power plant). The problem is that Wise County is not in Green’s district—the proposed reactor was at issue in House District 45, where first-time Democratic candidate Josh Outsey ran and lost against a Republican incumbent who has held the district for 31 years. Green reports that the billboard ads also diverged completely from her campaign messaging and hurt her cross-over appeal with conservative constituents. Photos of the billboards reveal the contrast between the consultant’s fear-driven messaging and Green’s coalition-building messaging.

The Virginia Democratic Party, whose steering committee is controlled largely by suburban Beltway Democrats and a state chair, Lamont Bagby, whose district represents Richmond in the State Senate, did not respond to Barn Raiser requests for comment on their support for rural candidates in the 2025 cycle.

Still, Green sees the grassroots organizing she began as a candidate is snowballing. Green describes what is meant to run for the people in her district:

It’s been very inspiring to me to engage with Democrats who have felt that the Democratic Party does not care about them. They haven’t had anybody to get behind. They have gone to the ballot box and had nobody to vote for House of Delegates since 2011. So it engaged and energized people. We’re building a coalition now and it’s not going to stop just because the election’s over. We’re going to keep momentum going.

Recruited by progressive philanthropist and organizer William Ferguson Reid, Jr. to run, Green brought a history of advocacy for affordable housing and community development to the ticket. Her vision inspired community partnerships with county agencies, philanthropic groups and area nonprofits that weren’t happening before.

If Republican donor sheets rack up corporate donations by hundreds of thousands in this corner of rural Virginia, it’s tempting to think that the Democratic party is the party of the little guy.

READ: Forty Organizations Offer a Plan to Revitalize Rural America

But for rural and small town voters, the perception that Roosevelt’s New Deal Democrats have been traded for corporatists in the state and national party leadership remains strong. This will continue to be the case so long as Democratic leadership shakes hands with corporate and white-collar interests, holding tightly to fundraising purse strings.

Voters noticed how Spanberger pulled back from labor protections. Meanwhile, down-ticket Democrats like Green are winning back voters by lining up with labor and by preaching the New Deal gospel on Main Street. Republicans exploit this disconnect for all its worth. When voters in rural places go to the ballot box, the Democratic culture peddled from the top doesn’t look much different than what the Republicans are doing behind the scenes. The irony is that Republicans have sold rural America hook-line-and-sinker that they’re the party fighting for the working man when, in fact, they’re the ones bowing to conglomerates, corporatists and hedge funds.

Rural America is not a monolith. It’s diversity increases yearly with shifts in demographics on par with metro centers. But there is a connection between the divisions that fester among those who feel left behind by America’s dominant, urban-centric culture, paired with an explosive rise in social media use, an erosion of reliable hometown news outlets and an inheritance of white supremacy—a cultural and systemic failure occurring in both rural and urban society. This culture of division has been exploited by both parties for political gain.

When a Republican candidate hollers into a microphone at a community event that he is fighting for families and gun rights, it makes sense to people who are saturated with news entertainment that is focused on metro interests. When Democratic Party leadership dismisses rural districts as a monolith of “white rural rage,” as Tom Schaller and Paul Waldman put it in their 2024 book of the same title, they ignore our diversity and they deny generations of class-supremacy that’s disenfranchised all of us.

Democrats cannot overlook the fact the 2026 midterms are going to be difficult. The party of Trump will quadruple its efforts to take back lost gains. Look no further than what happened in 2018 and 2020 in Iowa. In 2018, Kayla Koether (D) ran as a great cross-over Democrat for Iowa’s State House, appealing to both conventional and organic farmers. She came within 9 votes of beating Republican incumbent Michael Bergan. In 2020, Bergan was ready for her and beat her by 1,400 votes.

In 2026, if the Democrats rest on their laurels, they do so at their own peril. Republicans here will thunder back, not because they have good policy but because Democrats have failed to create a party that welcomes candidates of diverse ideological and class backgrounds. Making gains in rural districts can happen if Democratic leadership supports Main Street and country-road members in their party. Votes coming in for Cindy Green helped elect Democrats at the top of the ticket. Will Virginia’s party show up for her next time around?