In the midst of the bleak secession winter of 1860-1861, retired Bucks County teacher Samuel Snyder wrote an urgent letter to Secretary of War Simon Cameron. After Southern enslavers had captured their state governments and hatched a plot to secede from the U.S. in a desperate bid to enshrine slavery and white oligarchy in perpetuity, Snyder advocated a “moderate” political response. “The radical abolitionists” who demanded emancipation and even Black citizenship, he explained, “have come out of the contest more unpopular among all parties than before.” Even amid the lawlessness of secession, the real danger he perceived was abolition.

As we face the crisis of fascist state capture, with roving bands of modern-day slave catchers carrying out public assassinations on behalf of the regime, Snyder’s ideas about an analogous set of crises are both puzzling and instructive. When I came across his account as part of my work as a historian and editor at the Freedmen and Southern Society Project, I was struck by his version of white moderatism, which totally misunderstood the situation he faced and the causes of the actual events already unfolding around him.

What led him to conclude that the white supremacist oligarchs waging a literal war against the Union represented less a threat to the democracy he claimed to support than emancipation?

The country faced a genuine crisis in 1860, one in which white supremacist extremists captured the machinery of the police state—militias and slave patrols—to pursue their wildest fantasies in plunder and repression. They harassed, murdered, and exiled white Southerners opposed to secession while limiting the body politic to propertied white men. As proslavery agitator James Henry Hammond explained in his famous “mud sill speech,”

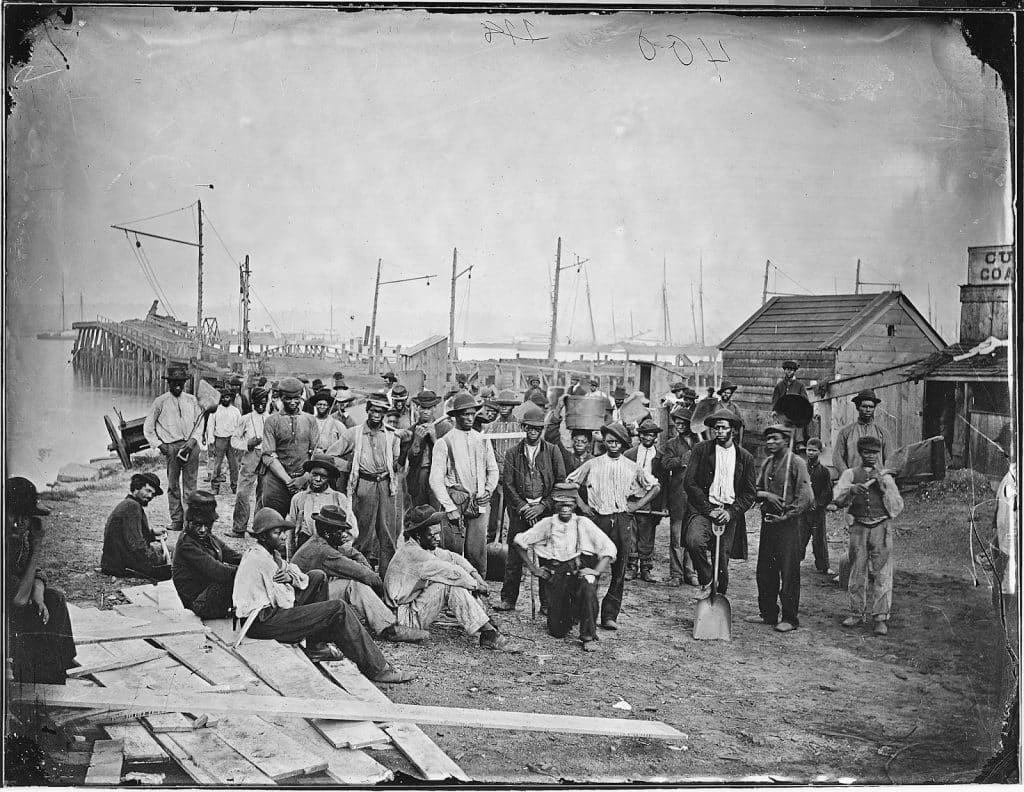

In all social systems there must be a class to do the menial duties, to perform the drudgery of life. That is, a class requiring but a low order of intellect and but little skill… Such a class you must have, or you would not have that other class which leads progress, civilization, and refinement. It constitutes the very mud-sill of society and of political government; and you might as well attempt to build a house in the air, as to build either the one or the other, except on this mud-sill.

Northern society was unnatural and unjust, in his thinking, precisely because it required this manual labor of white men and hordes of “semi-barbarian immigrants.” Never mind that it was largely impoverished and landless white Southerners who worked antebellum chain gangs and penitentiaries. Or whether “a system which has… kept a whole race in subjugation is itself worth maintaining,” as James Boggs demanded a century later.

Snyder understood the emphatically white nationalist project described by Hammond, but nonetheless imagined that “even here in Bucks Co. [Pennsylvania] through which an ‘underground railroad’ has been open for many years, an abolition lecturer and a Southern ‘fire eater’ would share the same fate before the tribunal of Judge Lynch, should either open his lips.” Snyder thus theorized that “the election of Mr. Lincoln is not an abolition victory, but the triumph of the democratic element in our Republic, enlightened by a free press and our public schools.” Only by suppressing abolitionism and disavowing Black political figures, he reasoned, could this “democratic element” of the Union be preserved.

Knowing what we now know — that Black Americans played a decisive role in advancing emancipation and a new national identity grounded in equality, at least on paper — Snyder’s ideas might seem puzzling. And today, most of us would hopefully recoil at his bizarre and grotesque ideas that so easily denounced freedom amid a literal attack on the very notion of equality.

Yet despite the way it contradicts a common, exceptionalist view of American history as marching inevitably towards equality, Snyder’s reactionary and inept reading of the politics of liberation represented a substantial contingent of the white liberal coalition that elevated Lincoln to the presidency. It is a set of ideas that—to be blunt—continues to plague the white “moderate” psyche today while drawing adherents into direct collaboration with white nationalist movements, figures, and ideologies.

Snyder’s missive to the Secretary of War included two primary characters who typified, in his thinking, the dangers of secession and abolition. The first of these, “Robert Tyler, the leader of the secessionists here,” comes across in Snyder’s account as a reasonable thinker worthy of debate. As Snyder told it, “I reviewed his course, together with some of his public letters and speeches, in some of our County papers, which, I fear, intensified the feeling against him here, for he was withal a good hearted fellow, and we were personal friends.” Notice that Snyder’s objection to Tyler grew not from his support of Black subordination, but his support of secession as a tool for advancing it. And in fact, he considered the slavery-apologist and secessionist Tyler, the son of former President John Tyler, a close friend and regregretted that his support for slavery and secession forced him to flee Philadelphia in early 1861.

READ: Racist Mass Violence Isn’t Incidental To White Conservatism—It Is Its Defining Feature

The “moderate” Snyder, then, did not consider Robert Tyler and his encouragement of a literal war against the Union to be dangerous so much as unfortunate.

Robert Purvis was the second primary character Synder used to muddy the waters of slavery, white supremacy, and secession. “I have nothing against Mr. Peirce,” Snyder wrote, “he is a good neighbor, but he visits, and his sisters walk, and ride with Robert Purvis and his sons, a wealthy mulatto of Byberry.” Mere association with Purvis, “a wealthy mulatto,” was grounds for suspicion.

So who was Robert Purvis and why was he so odious that mere association with him warranted exclusion?

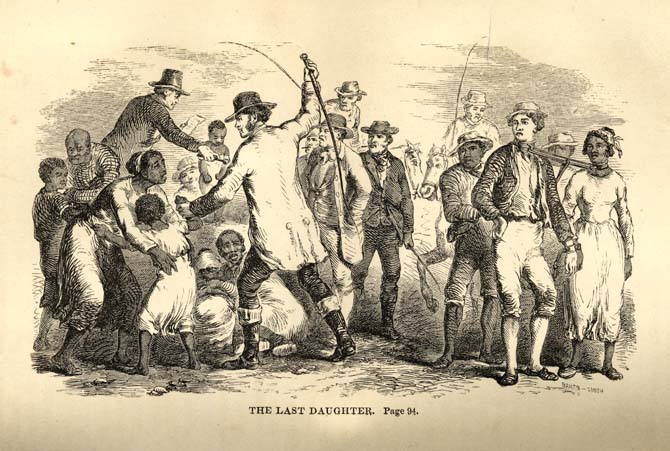

Purvis was a renowned antislavery agitator whose militant resistance to slavery led him to organize the Vigilant Committee of Philadelphia to resist slave catchers and help enslaved people escape to freedom. When William Wells Brown, an escaped slave and visionary Black historian and intellectual, visited Philadelphia on behalf of the abolitionist newspaper The Liberator, he attended a vigilance committee meeting to a warm welcome from Purvis. “He assured me,” Brown wrote, “that if the man who claims my soul and body as his property, should undertake to carry me out of that city, he would find a formidable obstacle in that audience, and the hearty response from the multitude that were present, satisfied me that I was at least safe for the time being.”

Not only was Purvis a militant abolitionist willing to defy the law and the slave-catching squads who scoured free cities looking for Black residents to kidnap into slavery, but he was also an uncompromising advocate for democracy and full enfranchisement. In 1838, after Pennsylvania’s new constitution stripped its Black citizens of the right to vote, it was Purvis who wrote the response. “When you have taken from an individual his right to vote,” he argued, “you have made the government, in regard to him, a mere despotism; and you have taken a step towards making it a despotism to all.”

Invited to speak at the national gathering of the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1860, Purvis excoriated white Northerners for their tepid, incrementalist approach to emancipation. After all, Purvis observed, “I belong to the class who, here at the North, are declared by the highest tribunal known to your government to possess ‘no rights that a white man is bound to respect.’” “Thank God,” his accusation thundered, “I have no willing share in a government that deliberately, before the world, and without a blush, declares one part of its people, and that for not crime or pretext of crime, disfranchised and outlawed.”

So why did Snyder think even association with Purvis was grounds for political exile?

Perhaps it was his longstanding support of full enfranchisement. Maybe it was his notorious defiance of the legal system of slavery and its henchmen. Or maybe it was simply because he was Black.

Whatever the case, Snyder’s unwillingness to embrace abolition not only failed to understand the causes of the secession crisis as it launched the country into a devastating war, but likewise misunderstood the way forward towards the democracy he claimed to support. There could be no rule of law as slave-catchers prowled free urban communities for Black flesh for the slave market. There could be no democracy under the expansive restrictions on voting rights, restrictions that even excluded propertyless white men. No education or “progress, civilization, and refinement” under a system that restricted Black Americans, white women and girls, and most working class whites from the promise of an education.

In embracing these systems of repression, as Purvis correctly argued, white Americans “have taken a step towards making it a despotism to all.” Or as Fannie Lou Hamer put it more than a century later, “until I am free, you are not free either.”

Today we face yet another crisis of white conservative lawlessness. But there can be no room for “compromise,” no “good hearted” Robert Tylers to placate and appease. Now, as then, the way forward lies in destroying their systems of repression once and for all, and in banishing forever those who created and operated these instruments of despotism and plunder. Only then will we be able to create something resembling genuine democracy and equality. Only then will we—all of us—be truly free.