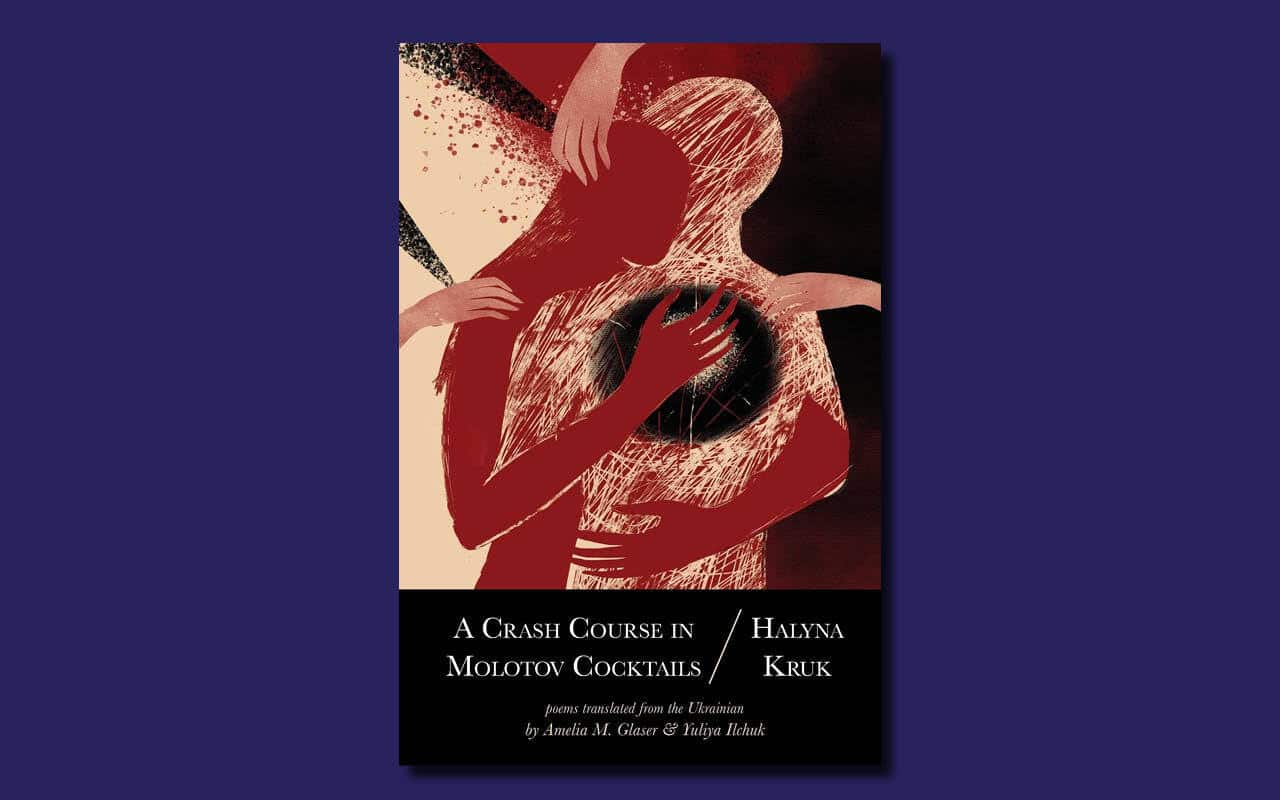

Halyna Kruk has given us a literary treasure with A Crash Course In Molotov Cocktails. The title gives so much away. What tragedy would force any of us to learn to make primitive weapons?

This book of poems is also a crash course in the heavy price paid by the Ukrainian people—a history of Russian aggression from Stalin’s purges and forced starvation, to Putin’s brutal and heartless imperial ambitions.

The poems are printed in Ukrainian and English side by side (translated by Amelia M. Glaser and Yuliya llchuk), a powerful statement by itself, like planting a flag, since Ukrainian poets were murdered and arrested for promoting Ukrainian culture under Stalin; and Putin repeatedly denies that Ukraine has its own identity, or even a right to exist outside of Soviet or Russian control.

“war kills with the hands of the indifferent

and even the hands of the idle sympathizers”

With these words Halyna lets us know that she is not merely speaking of the wounds of her people, her nation; she is showing us the template unfolded in Nazi Germany, or present day America.

Kruk evokes the value of Ukraine soil, knows that her nation is the coveted “breadbasket” that Stalin once led to famine in 1932 and what Putin seeks to “De-Nazify” in order to possess her riches. A “special military operation” based on alternative facts.

Kruk verbalizes one basic fact: from dust we come, to dust we return. Yet she transcends brutal reality, reminds us of the constant search for meaning, the search for truth in the between-spaces that our bodies and souls occupy.

How do you transcend war? The subject is so heavy, the details so brutal. Artists seem obliged to record every abomination, yet they seem equally obligated to speak of beauty, remind us of another world that exists, that refuses to be changed by violence.

Some of Kruk’s poetry is universal, some only fully understood by those changed by war. In her poem, “I am not the stripped sycamore” she writes:

“I am not this house maimed by shelling…

This missile lodged in asphalt, unexploded

I’m the one that’s gone.”

She worries about the children, how long it will take to relearn pre-war things and she worries about adults in exile not knowing if their home or city is still there. And she educates us on how war gives you no choice of what you wished for, how it surprises you to learn what you are capable of…

“… had a crash course in Molotov Cocktails from a bartender.”

Kruk knows how war strips you of your innocence, you grow old fast, lost, and awkwardly learn again how to touch and embrace. She has an exquisite line that captures centuries of war, “God, i have no clue what one says to someone pulled from the cross…”

And follows that with the incredible understatement, “we’ll come out of this changed.”

She has no interest in quieting the voices of anger, well aware that individuals and even television networks start to question the voices of reason when the sounds of hatred are allowed to drown out the sounds of love; and people feel they can do so little they resort to prayer. In the end she cannot be a bystander, she knows the poet is the voice of the dead, as she eloquently puts it in her poem, “in the trenches”:

“someone, when it’s all over, will put this in writing…

as though we were really truly among them.”

Halyna Kruk has spoken and continues to speak, of human bones and unexploded mines, and borders between our side and their side, how soil resists nationalism; how there is no past or future in war, just an eternal now “that bears no fruit but bitterness.” This is her darkest statement which she contradicts by her own existence as a human being and an artist.

Perhaps what defines the artist is the ability to never surrender belief in the possible, the refusal to accept brutality as the final word, even while witnessing destruction. She ends her poem “and for this pain” with the line, “i’m Lot’s wife, who looked back at the world one last time.”

She is not devoid of cynicism (“avoid someone else’s war until you get your own”), but cynicism does not get the last word. She ends the book with an affirmation of her identity coming through others:

“i am the last land…

i belong to the people…

i don’t want to walk toward a dead end…

and so, it begins with me…

i am we.”

This is poetry that documents the carnage of war but does not exclude the things that refuse to be extinguished by suffering: the scent of flowers, birdsong, every offspring of beauty, like literature itself, struggling to exist in the world.