The late rapper Tupac Shakur had a tattoo saying thug life across his stomach, but the meaning of this tattoo is often misinterpreted to be negative or criminal. In fact, Shakur once explained in an interview that THUG LIFE was an acronym standing for “The Hate U Give Little Infants Fucks Everybody.” Tupac’s acronym still forms, for many, the core philosophy of thug life: Children are the future, and so filling children’s minds with hate, raising them in an oppressive political system, and asking them to accept horrendous things like racism, sexism, and police brutality, has a snowball effect that eventually destroys life for everyone, even the oppressors. Angie Thomas titled her 2017 young adult novel The Hate U Give from the first part of the THUGLIFE acronym.

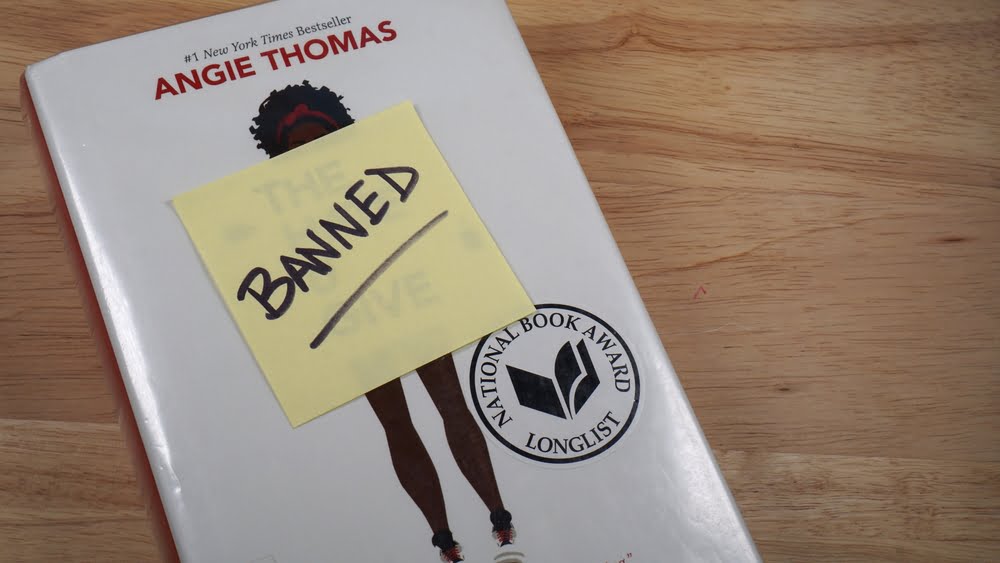

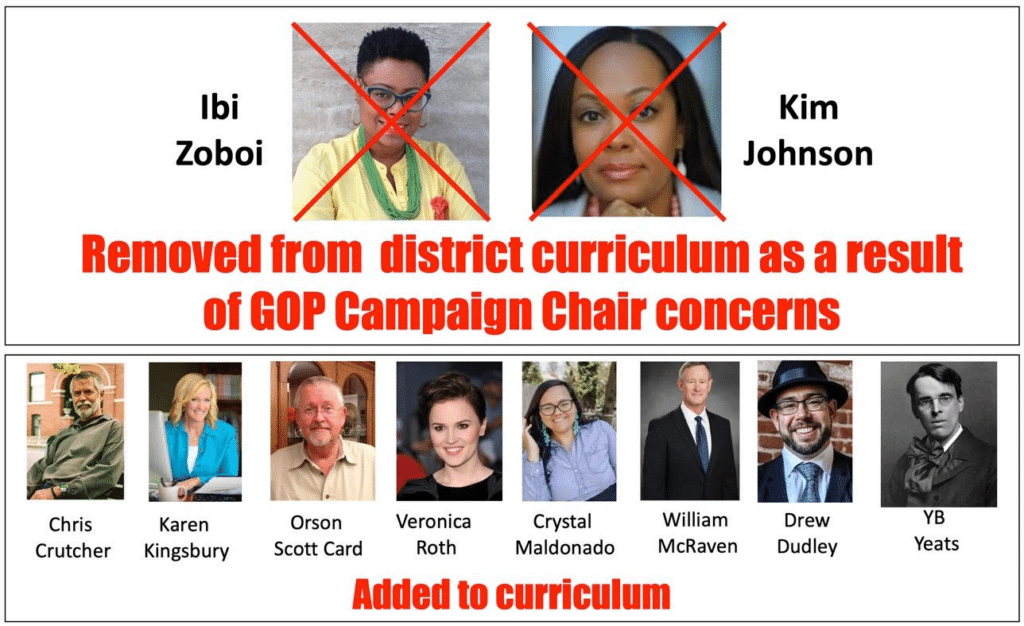

I’ve made a departure from my usual nonfiction book reviews for several reasons. First, The Hate U Give is a novel that has been on Pennridge School District Reading Olympics works as recently as 2021. Pennridge is also in the middle of a book purge and has removed works from two Black female writers already. The author of The Hate U Give, Angie Thomas, is a Black female writer. Some school districts in Texas have disallowed this book since its publication. I currently participate in a book club that meets about once a month to discuss fictional works that have been recently banned (or are slated to be banned) in at least one school district in the United States.

Second, this work addresses very timely topics regarding race, class, policing, trauma, despair, and having to navigate social relationships in two very different communities.

Third, even as a fictional novel written before George Floyd’s murder in 2020, the story could have been written from an actual Black 16-year-old girl’s life journal. Privileged communities, especially young people from such communities, need to know what it is like to live in places where there is little economic opportunity and where policing has been militarized to keep those from such places “in line.”

The book’s protagonist, 16-year-old Starr Carter, is a Black youth living in the housing projects known as “The Garden,” but straddles two worlds as her mother has her and her brother through scholarships enrolled in private, white, suburban Williamson prep school. Starr feels she must be two different people … one person for the “Gardens” and one person for her school community. This code switching is a common phenomenon for Black and mixed-race people to feel like they are passing as the dominant majority or “fitting in.” Throughout the novel it’s clear that Starr does not feel fully accepted in either world. She has one foot in her home community where folks don’t trust her because she attends the rich white school, and the other foot in the Williamson school where she “polices” her language, tone, and mannerisms to not be seen as the “angry Black girl.” This tension clashes into a boiling point early in the story when Starr witnesses a police officer murdering her friend Khalil after a traffic stop. Before this incident policing historically terrorizes the community of the Gardens, with the militarization “justified” because of drug and gang activity. In fact, Khalil’s murder cruelly triggers Starr because of a shooting Starr witnessed several years earlier when her friend Natasha was killed – caught between rival gangs’ crossfire. Starr’s father, Maverick, a former Black activist and ex-prisoner explains the despair of their community by white supremacy and the economic injustice, how it warps their young people, and draws the dangerous ire of racist militarized policing.

Starr must come to grips with the toll code switching takes on her psyche, especially as she is shoved into the spotlight as the witness to the tragic event that gets national attention. She is under enormous pressure to tell the truth about her friend’s death: that he did not threaten the police officer during a traffic stop and that she will have failed if the police officer doesn’t get charged. She knows Khalil has made mistakes in his gang connections but knows he was not a threat during the traffic stop. Her discomfort about Khalil’s gang involvement resolves as grief in learning the reasons for this involvement and she ultimately honors him, forgives herself, and moves on to memorialize him. As a minor she’s initially a confidential witness and is not comfortable sharing with her friends and boyfriend at school her status as the witness to Khalil’s murder.

Keeping that secret from those at school is an additional burden. It interferes with her relationship with her white boyfriend Chris and her closest girlfriends Maya and Hailey. The story takes the reader through shifting relationships as some become true allies, and others are revealed as false friends and dropped for that reason.

As the story unfolds, Starr ultimately reveals herself as the witness to both communities and makes a very public appearance in the protest that follows the police officer’s acquittal. Starr ultimately becomes her true self to both of her “worlds.” Those in the Gardens who found her untrustworthy come to admire her courage in speaking out for Khalil, and her vulnerability about being “real” at school strengthens her true friendships.

But not all in the Garden neighborhood were happy about her honesty and some violent consequences were visited on her father’s store as a result. The sad thing is it was unclear if it was from a gang leader or law enforcement.

As a parent, I also think about the pull to give children the opportunity for a better life. As a white parent, I never have to think about or talk about the dangers of race-based violence on my kids. Starr’s mother put her in a private school to protect her after her friend Natasha was killed. I can only imagine the tightrope parents walk raising Black children to protect them from despair of the realities of racism versus the dangers of not being careful enough in a racist world. I consider not having that burden a privilege of being white and raising white children. I have felt I had a duty to talk to my kids about their racial privilege, too. Teaching about racism makes my kids more compassionate. Teaching about racism to Black kids hopefully protects them. Tragically, as we all know, that’s not a guarantee.

One takeaway that’s universal is this: as scary as telling the truth can be, it honors the authentic self and aligns one’s life in integrity. This is not easy but worthwhile for a satisfactory life.

If I could require every student to read The Hate U Give I would do so. Nuanced discussions about race and class oppression and violence, both intra-community and state sanctioned, must be fearlessly encouraged for true healing to begin in our communities and nation.

For now, let’s reflect on some names from real life honored in the pages of this story:

“Oscar Aiyana Trayvon Rekia Michael Eric Tamir John Ezell Sandra Freddie Alton Philandro

It’s even about that little boy in 1955 who nobody recognized at first—Emmett. The messed-up part? There are so many more.”

I’m thinking I’d like every adult to read this book too.