I remember growing up hearing about the dangerous murderous “terrorist” Angela Davis as one of the FBI’s most wanted for allegedly murdering a judge in California. At the time I swallowed the media narrative, so carefully crafted from those in powerful positions. Many years later after her trial and acquittal and return to teaching and writing, I have had the privilege to hear videos of her speaking at workshops and panels on philosophy, politics, feminism, and intersectional social justice. My view of the author changed as a result.

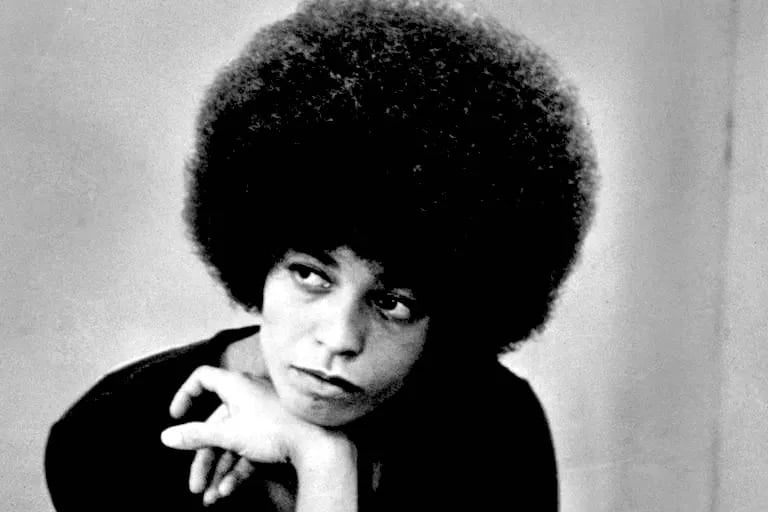

In 1974, college professor and political activist Davis reluctantly, at the young age of 30, wrote her autobiography. As a young woman dedicated to social justice, she wanted her writings to be about the work … not about herself. At the urging of friends, however, and with the help of her editor, the renown Toni Morrison, she agreed and focused her life story on why and how she works to root out white supremacy and economic inequality. At this point, having just celebrated her 79th birthday, Davis has lived and served an additional 50 years and has added two additional forwards to two new releases of her biography.

Angela Davis was born January 26, 1944, and in 1948 moved from the Birmingham Projects to the Dynamite Hill section of that city in Alabama, which was known in the 1950s for neighborhood bombings intended to intimidate and force out middle class Black families. Davis’s family, along with all other Black families at the time, experienced the terror of the Jim Crow South racism. She recounts that she personally knew three out of the four little girls who died on September 15, 1963, at the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, which was a turning point in the Civil Rights Movement. Davis left Alabama when she was given the opportunity to attend Elisabeth Irwin HS in Greenwich Village, New York City, and was recruited into Advance, a Marxist-Leninist youth organization. Later, her intellectual journey continued as a student of French Studies at Brandeis University, then later studying philosophy at the University of Frankfort in West Germany where she studied under Herbert Marcuse –a leading figure in the New Left. When Marcuse was given a position at the University of California San Diego, she continued her post-graduate studies before completing her doctorate at Humboldt University in East Germany. During this time, Davis became increasingly convinced that far left political causes were the key to eliminating economic injustice and racism in the United States and globally. Therefore, in addition to her teaching position at UCLA which began in 1969, she became active in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the Communist Party, the Black Panther Party, and worked to support political prisoner. Davis became an active supporter of the Soledad Brothers, three prisoners in Soledad Prison who had been wrongfully accused of the murder of guards inside the prison. Because anti-Communist sentiment in the United States and the FBI’s surveillance and targeting of groups such as the Black Panther Party, politically left organizers became convinced that arming themselves for personal protection was vital to surviving and carrying out activist causes. Davis had purchased firearms at a pawn shop on August 5, 1970.

Two days later, one of the defendant’s brothers, 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson gained control of a courtroom in Marin County California, armed the defendants, and took hostage the judge, prosecutor, and three female jurors. As Jackson transported the hostages, one of the defendants and the police exchanged fire, killing the judge, the defendants and Jackson, and injuring the jurors and prosecutor. Because of the straw purchase, Davis was charged under California law with murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy since the shotgun used in the shootings was linked to the judge’s death. Ironically, Davis had been fired at the time from the University of California at Los Angeles where she was teaching because of her membership in the Communist Party. Davis then went underground and hid at various friends’ homes until the FBI captured her in October 1970. Without even being present at the crime, Davis became one of the FBI’s Most Wanted until she was apprehended. They alleged the guns were hers and charged her with murder, kidnapping, and conspiracy to commit murder.

Davis and her work for those unjustly imprisoned, for her anti-war activism, and her international solidarity work had gained her global attention. Because of her unjust imprisonment, there was a huge movement to free Angela Davis.

She was held without bail in terrible conditions both in New York and in California for 16 months until she was granted a bail hearing, which she was able to achieve. The national attention afforded her the funds to make bail and excellent legal counsel, so she was ultimately acquitted of all charges in San Jose, California, on June 4, 1972. She attributes this to the disproven theory (argued by the prosecutor) that she masterminded the event in the courtroom because she was in love with Jackson’s brother George, imprisoned in Soledad, and was setting up a way for him to be released through demands over hostage negotiations. The jury did not buy this theory so conspiracy was off the table. Her defense instead made a compelling argument that she was unjustly imprisoned by a politically violent state system of law and order – one that protects only the powerful and binds the powerless.

Much of her memoir shows the systematic targeted harassment that Black organizations endure at the hands of the Department of Justice. For instance, there was sweeping surveillance of various Black Panther Party members and destruction of their headquarters and offices in more than one location. Targeted harassment made many members feel they needed to be armed for their own protection, creating a dangerous environment for communities working toward social justice, especially dismantling white supremacy.

In her preface to the 2021 edition, Davis eloquently discusses how and why she continues to fight the criminal justice system, militarized policing, and the prison industrial complex. She is more convinced now that we are “witnessing the perilous repercussion of neoliberal individualism” and that we need to “engage in critique of our relentless centering of the individual.” She talks about the organizing “and uprisings related to policing in the wake of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor,” and the” collective awareness of structural racism which crystallized during the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Davis also examines how her understanding of intersectional issues around gender and sexuality have deepened over the past 50 years and how it’s connected to the struggle against racialized economic oppression and capitalism. For example, the Third World Women’s Alliance, an organization that had supported the movement to Free Angela Davis, worked to expose the “sterilization abuse targeted women of Puerto Rico as well as Black women in the South.” The Alliance developed this in the same framework as that of abortion rights.

Davis describes in this latest preface how she was active in the Communist Party until 1991 when she and others decided to resign over the failure of the inner party structures to be more egalitarian in power sharing. She and her group then formed the Committees of Correspondence for Democracy and Socialism.

One consistent thread throughout Davis’s life work was her commitment to expose state violence: the violence of the police, the violence of prisons, and how these forms of “violence infuse the communities they target, sometimes further enacted by the very individuals who are their victims.” State violence is the tool of capitalism which uses a racial framework for economic repression.

This biography narrating the first 30 years of her life traces her childhood in a deeply racist Jim Crow South, her philosophy studies, her radicalization to equitable just causes, and her direct experience within an unjust violent criminal “justice” system. Davis has written nine other books on race, class, gender, culture, state violence, prisons, and political movements. Not directly mentioned in the biography, Davis came out as a lesbian in the 1990’s but she does mention her partner Gina Dent in her preface to this latest edition.

It was truly an honor to read Davis’s accounting of what happened to shape her avocation, how pervasive state violence is in the United States, and how we can connect our current struggles to struggles of the recent past. This is history from which we can all benefit once we know of it. I chose “walls turned sideways are bridges” for my review title directly from this book because Davis truly embodies this philosophy in her life’s work.