On the evening of September 27, 2022, Pennridge school board director Ricki Chaikin announced that “smut and filth” existed in our school libraries. Chaikin claimed, “while it is a sad fact that implementing policy that prohibits providing pornographic material to children is necessary, it is necessary and not unique to Pennridge.”

In support of her statement, board colleague Jordon Blomgren recited an excerpt from the young adult novel “Allegedly” by Tiffany D. Jackson. The excerpt contained harsh character dialog peppered with explicit language. Chaikin warned that Tiffany D. Jackson’s book was in the high school library until just days prior to the meeting.

Blomgren’s and Chaikin’s comments were followed by the expedited adoption of three controversial policies. Not one of these policies were on the agenda for a final vote that evening. Some considered it a procedural sneak attack by the board, if not a violation of the Pennsylvania Sunshine Act.

Changes to Pennridge Policy 109 were aimed at culling our libraries of so-called “age-inappropriate” books, guided not by trained librarians, but by right-wing school board members’ politics. Implementation of the policy was to be guided by a new set of content standards. The new standards were defined by the school board itself. Policy 109 was revised to include “sex” 32 times.

I was somewhat stunned by the level of rhetoric being used that night. Weighted words like “pornography,” “smut,” “filth,” and “criminal” were employed to describe library books. I needed to know what content would inspire such over-the-top language. I immediately ordered my own copy of “Allegedly” from Amazon.

The next morning l navigated to the Pennridge High School library’s online card catalog. I stumbled across something peculiar. “Looking for Alaska” by John Green ‘0 of 9 copies available. Estimated wait in days: 358-359 Days.’ Every single copy of the young adult novel was checked out for an entire year.

I kept browsing. It turned out that the same was true for many other titles including (but not limited to): “Sold” by Patricia McCormick, “Flamer” by Mike Curato, “Sex is a Funny Word” by Cory Silverberg, “A Queer History of the United States for Young People” by Richie Chevat, “A Court of Thorns and Roses” by Sarah Maas, and (no surprise) “Allegedly” by Tiffany D. Jackson. It would appear that the culling had officially begun.

I emailed Pennridge Superintendent Dr. David Bolton that morning. I asked if he would provide a list of books currently removed from circulation under Policy 109. He declined to provide that information. Bolton did say that he had personally checked out “Allegedly” to read after the reported content concerns.

I later asked Bolton specifically about the ‘0 of 9’ copies of “Looking for Alaska.” He replied:

“I have confirmed with the HS librarian that Looking for Alaska is also being reviewed by her based on the updated criteria in Policy 109. All of our librarians are in the process of evaluating their collections based on the new policy language. I certainly hope it doesn’t take 359 days for the review. I assume that has to do with a default setting in the system.”

For several weeks, multiple parents emailed the district requesting a list of books pulled from circulation as a result of the new policy. To my knowledge, that request was denied in every instance. I submitted a “Right-to-Know” request for “any log that lists library books that have (or are currently being) challenged, reviewed, or removed.” After waiting over a month, that too was denied. According to the school district’s official response, no such record was being maintained.

Policy 109 was presented by the school board as a step toward better transparency for parents. I was starting to realize their promise was not going to be kept. But what I could not foretell was just how far the school district would go to remain opaque about this policy’s implementation.

I was growing increasingly concerned with the lack of due process. It is not typical practice to remove every single copy of a library book from circulation simply because a content concern is raised. A formalized review process is almost always conducted first, and for good reason. As explained by the Education Law Center: “Book removals by school districts that rely on irregular procedures without standards or a review process are more likely to violate the First Amendment.” The district was seemingly following a guilty until proven innocent model for their book purging.

And can we talk about “Looking For Alaska” for just a moment? This is not some trashy dime store romance novel. It is a modern day classic with established literary merit. “Looking For Alaska” has earned prestigious accolades, including the Michael L. Printz Award for Excellence in Young Adult Literature. It is a book that is taught as a part of English curricula in public high schools across the country. Even more important, it is a bestselling work of young adult fiction that teenagers actually want to read. I do remember hearing stories, years ago, about parents objecting to this book being taught as part of English curriculum, but Pennridge is removing it from the library? Really?

As for “Allegedly,” I received my copy in the mail. I was eager to see the evidence of “smut and filth” presented by the board. I read the book.

It turned out that the excerpt recited at the September 27 meeting does not even exist in the novel. That’s right folks. Unless you consider unrelated phrases from completely different sentences, paragraphs, and chapters (artificially stitched together) an “excerpt” then, no. What was read that night was not only out of context, it was a total mischaracterization of the book’s contents. Either Chaikin and Blomgren were knowingly misleading the public, or they didn’t even bother to read the book before championing its removal.

Is there profanity in the book? Sure. Is it gratuitous in nature? No. Is the explicit language necessary to the story? Absolutely. Regardless of your viewpoint on censorship, it clearly demonstrates why the public should have an opportunity to defend a book before it is banned.

And let’s be clear, banning is exactly what is at issue here. Faculty checking out every copy of a library book in perpetuity is a book ban. The fact that an official decision has not been reached to permanently remove a book does not negate that reality. Furthermore, refusing to tell the public which books are currently impacted by these actions makes this whole process even more problematic.

Thankfully the Right-To-Know (RTK) Law exists in Pennsylvania. Members of the public have the right to access records from a government agency. It is for situations like this that the law was established.

I submitted an RTK request for a record that I knew must exist. A report from the Pennridge High School library database of “all titles checked out by those patrons that are NOT Students.” I waited 5 business days, with no response from the district. I immediately opened an appeal with the PA Office of Open Records. Soon after that, I was contacted by an attorney representing the Pennridge School District. She emailed me a report and requested that I withdraw my appeal. I opened the report and was surprised by the contents.

Not a single controversial book was listed on the report. Not even “Looking For Alaska.” According to the online catalog, nothing had changed. All of these books were still checked out and all still not due back until September 2023. The report was obviously incomplete and unresponsive. What the hell was going on? I was going to need help. I hired an excellent open records lawyer, Joy Ramsingh of Ramsingh Legal.

We started by attempting to negotiate directly with the school district’s lawyer. We wished to come to an amicable solution. We wanted to spare any unnecessary legal expense for both myself and the district. Maybe there was a simple misunderstanding about the request? Perhaps there was a technical error that needed to be rectified? We communicated frankly about what I was seeking and why we believed the report to be inaccurate.

The district eventually produced a second report. The first report was a snapshot. It purported to show all books with the status of checked out by non-students at the moment the report was generated (10/28/2022). The new report was transactional. It purported to show all check-in/check-out transactions made by non-students for a given timeframe. The district presented us this report for the timeframe of 9/28/2022 – 10/31/2022.

I opened the report. I scrolled down to the transactions made on 10/28/2022. My jaw hit the floor. Every copy of “Sold,” “Looking for Alaska,” and “A Court of Thorns and Roses” were apparently checked back in on the same day that my original snapshot report was generated. But by 11/1/2022, those same books were checked back out again.

Was this just an unfortunate coincidence? Would it be unfair to speculate that a faculty member might have checked all these books back in, temporarily, for the sole purpose of keeping them off of the original report? I would certainly hope not. Either way, I guess that might explain why those titles were absent. Case closed, right?

Well, not exactly. There were still several books missing from both reports. We never mentioned these titles to the school district’s attorney up to this point. All these books happened to address LGBTQ or gender identity topics. These books, too, had been checked out since September 2022.

So we went back to the school district’s attorney, yet again. We presented evidence about one of the missing titles, “Flamer” by Mike Curato. At that point, the district provided a new snapshot report. Miraculously, these books now appeared.

But still, the latest report did not comport with my observations of the online card catalog or the other reports. Still titles were missing. “Sex is a Funny Word,” for example, did not appear in any of the three reports. It, too, had been pulled since September 2022. I had all the receipts; emails and timestamped screenshots.

At this point, negotiations had reached an end-pass. I had given the district ample opportunity to act in good faith. I was confident that we had sufficient evidence to prove that the school district was not being responsive to my request. We continued forward with the appeal.

The school district submitted their first written argument to the Office of Open Records. My initial reaction was “wow, they must really want to win this appeal.” It was 48 pages long. I could not imagine how expensive it was to compile such a document. I was also glad that I had sought my own legal representation. I would have never been able to challenge the giant bowl of legal spaghetti that Eckert Seamans threw against the wall.

My attorney effectively rebutted all their legal arguments for dismissal and presented our evidence. The most poignant part of what she wrote wasn’t even a legal argument at all. It was an eloquent way of saying “hey, cut the crap.” It read “It’s clear that the District understands exactly what the Requester wants. It’s clear that they could simply inquire with their faculty, determine which books are being reviewed, and then provide that list to the Requester. But rather than taking that good faith action, they are attempting to manipulate any loophole they can find within the Right-to-Know Law to ensure that the actions they are taking under the authority of this public policy are as obscured as possible from public view.”

It was so profoundly true. What I was seeking was not only public information, it was a matter of public interest. The information could have been gathered with a 15 minute conversation between the superintendent and his faculty. Instead, it had turned into a legal ping pong match, costing the district and myself a lot of money.

I am disappointed to say that, in the end, the school district did prevail in the Office of Open Records appeal (See Final Determination). The school district made no effort to prove, or even dispute, that the books I had identified were pulled by faculty. The ruling was also not a result of the school district’s attorney finding a brilliant legal loophole. In fact, Pennridge didn’t even claim that the reports were accurate. It all hinged on the sworn affidavit given by Superintendent Bolton in the final legal argument submitted by the district.

I learned that sworn statements can hold a lot of weight, even when they’re based on questionable facts. The District insisted repeatedly that they couldn’t create this report, despite obvious factual holes in their evidence. And even though the facts in this case were distinguishable from some of the previous database cases, the Office of Open Records accepted the affidavit as proof.

But hold on, faculty members are checking out books under student accounts? There are faculty members that don’t have their “patron status” updated in the system? There is absolutely no way for the school district to ascertain which books are checked out by students versus. faculty? I think there is something rotten in the state of Denmark. My lawyer has a myriad of follow-up questions for the district and we are appealing to the Court of Common Pleas. I’m looking forward to a judge reviewing the case. See our petition.

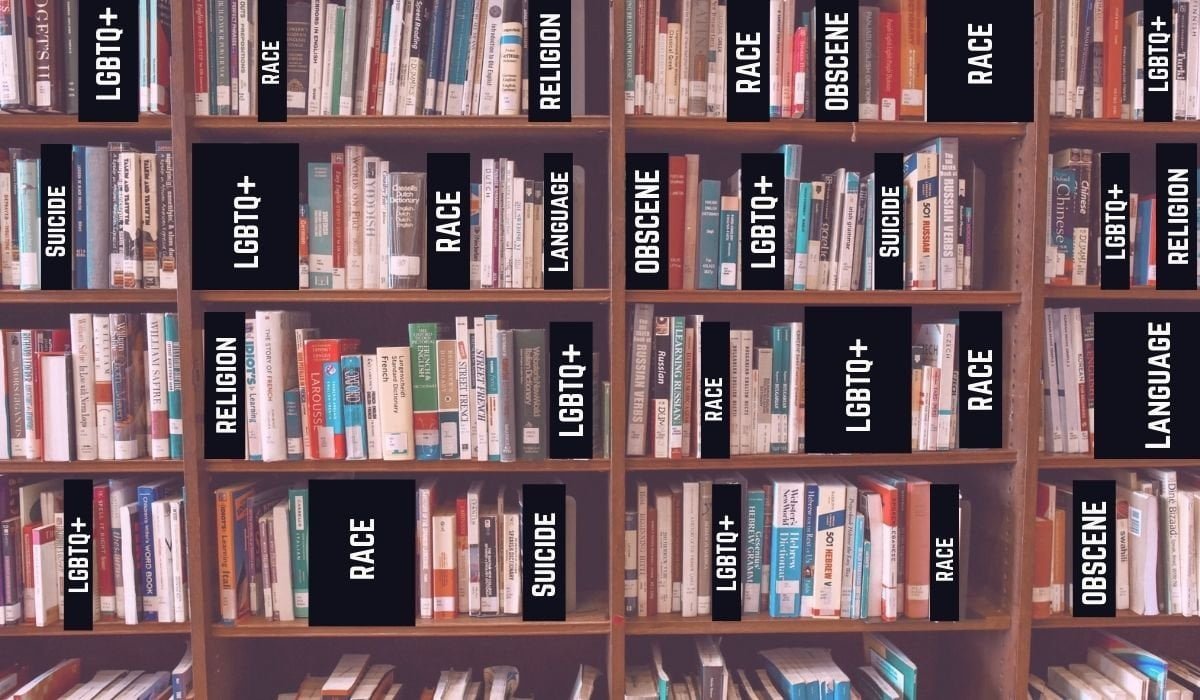

It is now March 2023. It has been over 5 months. All these books are still pulled. Don’t take my word for it, confirm for yourself on Pennridge’s online card catalog. Maybe you’ll find a few titles that I missed. You’ll start to notice a very common theme. These are books targeted by conservative political activist groups like Mom’s For Liberty. It has been common for people to use their favorite website, booklooks.org , as a tool to raise objections to books they never actually bothered to read.

So please, Pennridge, tell us what books you removed. If you are proud of what you are doing, then own it. At least allow us to have the conversation. Thinking you will successfully implement policy outside the eye of public scrutiny is a fool’s errand. Allow us to ask questions like:

- Why is a sexual education book rated for 10-12 year children, age-inappropriate for a high school?

- How is banning a book that deals with a very real issue, like child sex trafficking, protecting our young girls?

- Why can’t a book about the civil rights struggles of queer people share a library shelf with other books about civil rights?

- Do we really want to ban the debut novel of one of the most renowned young adult fiction authors alive today?

I am looking forward to having the debate.