In 1908, Henry Chapman Mercer began construction on his new home on a sizable, neat, squarish plot of land just outside of Doylestown. This new estate was to become more than just a home for the talented and wealthyMercer; it became a dedication to Mercer’s love of antiquity and 19th Century Romanticism. Having a keen eye for European architecture, notably medieval castles, Mercer’s unusual home is a mix of architectural wonders and pure imaginative fancy. A true renaissance man, Mercer paired this love of the past with early 20th Century conveniences such as electric lighting, a house-wide buzzer system, phone intercoms, numerous bathrooms with indoor plumbing, and several different heating systems in order to create this spectacular wonder and live at ease. His affection for simplicity and antiquity is reflected in Fonthill’s composition and design; built entirely out of reinforced concrete in an amazingly short time span of just four years, this concrete “castle for the new world”, as Mercer put it, is a reflection of himself as much as it is the times of a bygone era.

In March of 1913, W.T. Taylor wrote in an article for the architectural magazine, Personal Architecture, that Mercer had created a “visualized composite of impressions of Medievalism rendered in an essentially modern type of construction.” Taylor praised Mercer for his unique achievement of skillfully erecting something that was, at its core, a vision of his “reverence for the romance and charm of the old castles on the Danube and the architecture of the older countries.” Mercer himself described Fonthill a combination of “the poetry of the past with convenience of the present.” Influenced by artists such as Adrian Ostad, Durer, Gerard Dow, and Rembrandt, Mercer sought to create areas within the castle that, when manipulated by light and shadow, could create an array of visual perspectives unique to certain times of the day and very much dependent on how brightly the sun happens to be shining. The castles’ many windows allow natural light to penetrate the interior to which Mercer maximizes by constructing a number of decorative yet highly functional interior windows. When illuminated by sunshine, the stylized shape of the exterior window is reflected upon the bare concrete walls, passing over an interior window, and thus creating a sense of timelessness in its most simplest form. The often odd, though deliberate placement of the castle’s windows allow for a visual experience that can evoke a feeling of romantic longing and for just a few moments, can transport the viewer hundreds of years into the past and get a sense of what one might have seen walking through an ancient medieval castle.

Contrasted by dark corners and hallways, penetrating natural light provides the perfect backdrop to highlight the quiet beauty of Mercer’s skillful composition and design. Viewing a staircase or dark corner from a particular angle shows the artistic elements involved with carefully crafted concrete construction. Rounded corners give way to illuminated arched shadows that showcase a section of Mercer’s famous floor tiles, simple in shape yet give the composition a tone similar to an Italian medieval structure. The aesthetics of the concrete blends nicely with the clay tiles as both draw upon the simplicity of Mercer’s design.

Nothing should be viewed from only one angle and different viewpoints reveal the artistry of simple staircases and corridors. Curved rectangular staircases mash up against square wall tiles, hexagonal floor tiles and other angular shapes of the castle’s interior. Light splays out onto steps in geometric forms or melts away into the inky curvature of the concrete stairwell. The architect William Kleinsasser observed that Mercer’s decisions in his building of Fonthill reflected a “great sensitivity to light and its effects, particularly on things whose meaning and mystery are magnified by it; such as forms and spaces within other spaces, forms juxtaposed against other forms, glass, texture, color, and silhouette.” Exposed metal pipes and twisted-up wires, what could be assumed as ugly fixtures within a home, become a part of the backdrop and contribute to the overall form of the castle itself. Despite Mercer’s love of antiquity, he wasn’t necessarily a staunch anti-modernist, though he did envision his home as a sort of repudiation to the industrialized world. Exposed metal piping and electrical wires were a functional portion of Mercer’s everyday living and he managed to combine the antiquity of Europe’s ‘old world’ with his own innovation. Mercer was once quoted as saying: “The construction was nowhere concealed. From the first to the last, I tried to follow the precept of the architect Pugin: ‘Decorate construction but never construct decoration.’”

In 1966, Joseph E. Sandford of the Bucks County Historical Society wrote that while Mercer was certainly a romantic whose style and taste was fashioned after the Gothic Revival, a protest in part against the “ugliness of the industrial age.” He remarked that “the person for whom art is a living experience, chooses the works which have meaning for him and enjoys them despite the critics,” alluding to how Mercer valued functionality and form over pure aesthetics. However, Sandford critiques Mercer’s view of the medieval past as a form of “idealized medievalism” rather than a true and accurate portrayal.

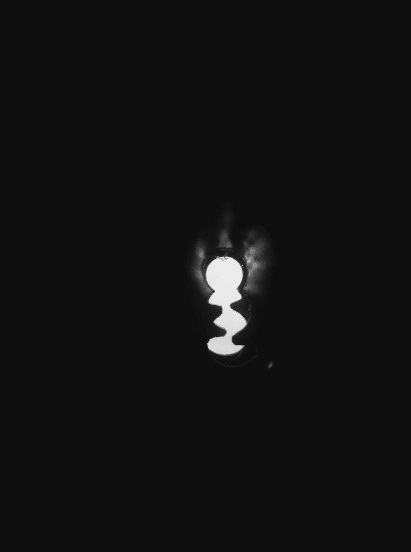

Yet, the artistry of Fonthill’s construction moved the architect Kleinsasser to describe it as a structure of mysteries filled with unexpected vistas and level changes as well as harboring strange niches and accidental alcoves. He alluded to how the castle comes alive with the changing light of the day, “like a forest or partially illuminated cave.” There is a stillness to the home, though it is not particularly unsettling, and does often feel similar to being inside a cave or ancient forest with mystery and shadow round every step. Fonthill’s corners, doorways, and corridors, even down to the individual craftsmanship of doors and locks, conjure up feelings of curiosity or mysticism. Peer through one of the castle’s locks and you’ll find an interesting combination of light and dark, wood and metal, and perhaps a feeling of intrigue, not perhaps unlike what Alice must have felt while peering through a door’s keyhole leading into Wonderland.

Mercer’s taste for the Romantic is evident in not only his architectural tastes and designs, it served as inspiration for several of his own 19th Century Gothic inspired short stories published only a few years before his death in 1930. Tales of mysticism and intrigue are woven together with surreal visions of the supernatural and the unexplained; danger and mystery infused with the romantical reminiscences of an aged and well-traveled scholar. As you breathe in the stillness of Mercer’s castle and amaze in the winding staircases, the dark niches, stunning columns and overall eccentric design of whom author James Michener, another Bucks County native, once called a “mad genius,” it’s easy to imagine Mercer wandering the many maze-like levels of his concrete castle with images of distant lands and explorations, lost ruins and mysterious characters wafting through his mind. Corey Amsler, Vice President, Collections and Interpretation of the Bucks County Historical Society sums up the castle’s overall character as an “enduring monument to its builder’s architectural creativity and romantic vision.”

Special Thanks to the staff at Fonthill Castle and to the wonderful librarians at the Mercer Museum Spruance Research Library.

Sources:

Amsler, Corey M. 2015. “Introduction.” In November Night Tales, by Henry Mercer. Valancourt Books.

Kleinsasser, William. 1967. “Poured Concrete Eclecticism.” “Connection”.

Meissner, Ise. October 1960. “Dr. Mercer’s Concrete Extravanganza.” Progressive Architecture .

Sandford, Joseph E. 1966. “Henry Chapman Mercer: A Study.” The Bucks County Historial Society.

Taylor, W.T. March 1913. “Personal Architecture: The Evolution of an Idea in the House of H.C. Mercer, Esq.” Architectural Record, V 33 p. 242-254.