Written by Kristian Hernández, Center for Public Integrity

Recent stories of migrant children working long hours and under dangerous conditions in the United States have shed light on how pervasive migrant child labor has become in this country.

In December, Reuters published the third part of a year-long investigation about migrant children as young as 12 working in Alabama chicken plants and in Hyundai-Kia supply chain factories in the South.

Two months later, the U.S. Department of Labor announced that Packers Sanitation Services Inc., one of the nation’s largest food sanitation companies, had agreed to pay $1.5 million in civil penalties after federal investigators discovered violations of child labor laws. They found the company had illegally employed more than 100 children, ages 13 to 17, all working in hazardous jobs at 13 meat processing facilities in eight states. The case was one of the largest in the department’s history.

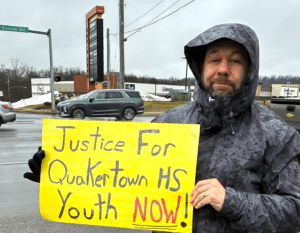

And most recently, The New York Times published an investigation showing migrant youths working dangerous jobs in violation of child labor laws in factories making well-known products including Cheetos, Cheerios and Ben & Jerry’s ice cream. According to the report, these child migrants are part of a “new economy of exploitation.” Days after publication, the U.S. Department of Labor and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announced new efforts to combat exploitative child labor.

“This is not a 19th century problem,” Department of Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said in an accompanying statement. “This is a today problem.”

Public Integrity spoke about the issue with Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez, a professor at the University of Illinois who has studied the history of U.S. policy on childhood migration. Padilla-Rodríguez uses media accounts, court documents and the records of various government and law enforcement agencies to help piece together this often-missing part of the nation’s history.

*This conversation have been edited for length and clarity. (Listen to Public Integrity · Full Audio Interview with Ivón Padilla-Rodríguez)

Q. How difficult has it been to uncover this part of U.S. history?

Most of what professional historians know about the history of migration from Mexico and Central America largely concerns adults. There’s this presumption in the historical literature that children didn’t migrate in the past, and that after the U.S. banned child labor in 1938, that they didn’t work.

These presumptions aren’t just harbored by professional historians, but they’re harbored by the professionals who control the research collections that historians go into to even be able to uncover these kinds of histories and make these claims.

I’ve encountered a lot of pushback in the research stage of this project. It’s been extraordinarily difficult to uncover the stories of these kids, certainly not only because of the pushback, but also because the groups of people that I study — poor, migrant, Mexican and Central American youth. They almost never left behind their own sources. And of course, they also had to cross the border clandestinely and avoid detection for their own survival.

So unless they encountered a person in a position of authority, say like a border patrol agent, or some other kind of law enforcement authority, their voices are pretty scattered in the historical record.

Q. Is exploitative migrant child labor a problem in the U.S. and how long has this been happening?

Yes, exploitative migrant child labor is a problem in the United States. It’s been happening for a long time.

I’m going to take us all the way back to the late 19th century when the U.S. experienced large-scale migration from places like Europe and Mexico and even Asia, in spite of exclusionary legislation that was meant to bar their entry. Among these immigrants who participated in this large-scale migration were children, and also, of course, eventually the children of immigrants. And they ended up working in places as diverse as railroads, mines, factories, domestic service and agriculture.

When the 1938 child labor ban was passed, it included really strict prohibitions for certain sites of work, mainly manufacturing and mining, but they also included an exemption for agriculture that still exists to this day. It’s been amended, of course. So the exemption has been narrowed since 1938, but it still exists.

Throughout the 20th century, one of the biggest culprits of migrant child labor exploitation were commercial farms and they were mostly employing, particularly in the post-World War II period, migrant Mexican youth. So, kids have been working for more than a century in this country.

And migrant labor use inhibits particular precarities that make their labor that much more invisible to historians, to lay people, etc., so this country has a really really long history of migrant child labor.

Q. The Department of Labor has seen a69% increase in children being employed illegally by companies since 2018. What do you think is driving this increase?

I think there are two main drivers of this recent increase in migrant child labor violations. The first is families’ extreme poverty. The second is restrictive immigration policy, which is a major reason that has to be attended to when thinking about why migrant children are ending up in these situations of violent or coerced labor.

So in terms of poverty, when there are no opportunities for social and economic mobility at home, let alone safety from violence, families and young people have to make these really difficult decisions to flee in order to survive, in order to not starve to death.

The COVID pandemic only exacerbated families’ food insecurity problems in countries of origin. There are also, of course, environmental crises that are contributing to these food insecurity, problems and families precarity. And because there are no opportunities for safe, efficient and lawful entry into the United States, young people often have to make these decisions to purchase the services of smugglers in order to get them across the United States.

It’s also restrictive immigration policy, not only the lack of lawful avenues for migration available to them, but also the militarization of the border that is making them vulnerable to exploitation to unscrupulous actors, and to something that’s called debt bondage, where young people in debt themselves for smuggling services, and they have to pay back their smuggling debts once they get inside the United States.

That’s how [young migrants] get coerced into these forced labor schemes. And that, in and of itself, also has a long history. It’s not something that is new either. In my own research, I study the origins of undocumented youth labor trafficking, which I saw in really significant numbers, particularly after the U.S. started militarizing the border in the 70s.

Q. Amid this increase in child labor violations,lawmakers in at least eight states have introduced bills so far this year to weaken child labor protections. How do state and federal policies contribute to the exploitation of child migrants? And is there a solution?

From my view, there’s an entire constellation of policies that are at play here. And that needs to be scrutinized if the U.S. hopes to meaningfully address this humanitarian problem and find a solution.

To start with the labor laws, there’s of course the issue of lax enforcement of stringent prohibitions that already exist that are supposed to prohibit the presence of minors in hazardous occupations. But there’s also the issue of the loopholes and the gaps in federal child labor law that make it possible for children in agriculture, for example, to work long hours in exploitative conditions at young ages and that’s totally lawful.

While we should vigorously oppose the loosening of state child labor laws, we also have to pay attention to the areas of child labor law where there aren’t sufficient protections for young people.

One thing that I also think really needs to be attended to in addition to labor law is education law and court precedents. Court precedents that guarantee even undocumented children’s right to education. This labor exploitation, as the New York Times exposé notes, is depriving children of their education.

We’re not only violating labor laws by allowing a child workforce to flourish, we are also violating compulsory school attendance laws and the 1982 decision in Plyler v. Doe, where the Supreme Court said that undocumented children have a constitutional right to public education K through 12, because of the Equal Protection Clause.

There are Republican lawmakers who have in the past said that their eye is on that court precedent to get it overturned. So, I think if states are trying to loosen state child labor laws, they’re also trying to diminish children’s legally protected right to education. I mean, we’re headed into really dangerous territory.

Q. What is one point you’d like to get across about your research and what you know about how U.S. policy affects exploitative migrant child labor?

What I mostly want to get across is simply that the U.S. has enabled migrant child labor exploitation for a very, very long time. And I think there comes a point where we must ask ourselves how this is also a history of, quite frankly, racism and white supremacy that has enabled a lot of this policymaking and these choices.

Most of the children that we’re seeing who are being deprived of their education, who are being exploited for their labor, who are not being afforded the protections of childhood, are non-white children, Indigenous children from countries that have been ravaged by U.S. intervention.

I hope people ask themselves: Whose childhoods in this country matter? Whose children matter? Because I’m increasingly of the opinion that childhood is becoming this racially exclusive concept and that’s unacceptable.

This article first appeared on Center for Public Integrity and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.