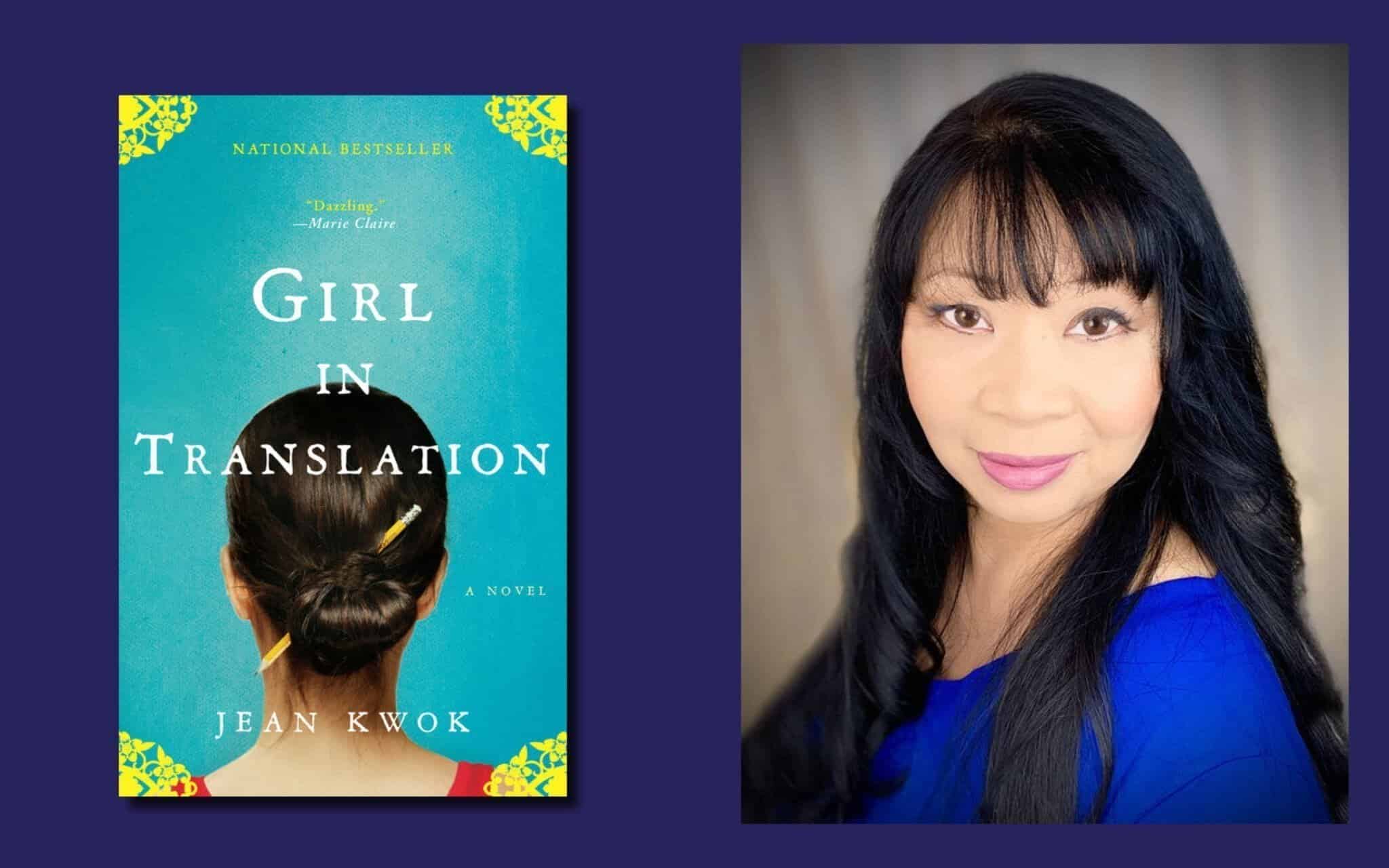

Since Central Bucks School District passed Policy 109.2 last summer, 65 books have been challenged for removal from CBSD school libraries. When award-winning author Jean Kwok heard that her book Girl in Translation was being considered for removal, she decided to fly into Doylestown from her home in the Netherlands to defend it.

Girl in Translation is the story of Kim, a young Chinese immigrant to New York, who learns to disguise her life as an impoverished sweatshop worker in order to be accepted by her public school peers. Kim becomes adept at translating between both languages and worlds. Kwok drew upon her own childhood experiences in writing the novel.

READ: The Bucks County Courier Times Fails Readers With Its Book (Banning) Policy Editorial

Girl in Translation has been featured in The New York Times, USA Today, Entertainment Weekly, Vogue and O, The Oprah Magazine, among others. It has won multiple awards including the Alex Award given to 10 books written for adults that have special appeal to young adults, ages 12 through 18.

Yet, despite the accolades the book has received for young audiences, it has been challenged in CBSD due to accusations by Moms For Liberty (a national far-right organization that School Board Director Debra Cannon is a member of) that the book contains “sexual activities; sexual nudity; mild/infrequent profanity; alcohol and drug use by minors; and abortion commentary.”

During public comment, Kwok noted that in the novel, there are four so-called “curse words,” and that the questionable material comes down to minor pot-smoking, non-detailed kissing and a non-explicit sexual encounter.

“This is a book about resilience, compassion and forgiveness. It’s about love between daughters and mothers. It’s a book of unity, not of division,” she said.

Kwok spoke to the Bucks County Beacon about why she came to defend her book, her experience at the school board meeting, and the impact she hopes her visit will make.

How did you feel when you heard that your book was being considered for banning?

I was really shocked. Like a lot of people, I kind of vaguely knew in the back of my mind that this was happening around America, but I hadn’t realized to what extent and how that movement was actually national, and that people were feeling so powerfully about it. So it was really shocking and disturbing.

After I began planning to visit Central Bucks, I started to hear from so many people on social media and across the country, friends of mine who are school librarians and educators in the U.S., and it just sounds like they’re under siege.

I learned that Central Bucks isn’t the only place considering banning my book. I heard that my book has already been banned in Clay County, Florida … my book, along with many, many others. I am sure that it’s not the only County that is considering this, because I think book banning has become very much a kind of copy-paste action.

How did you make the decision to come here?

I was contacted by Tracy Suits just to submit a short statement defending my book and I told her I’d consult with my publisher, and we’ll figure out what we want to do and I’ll get back to you.

I started to write the statement and the more I wrote, the more I thought, “I want to go there myself.”

I wanted to come to Central Bucks because I think a part of the reason that this is happening is that it may seem like authors are this kind of faceless, possibly malevolent entity that’s putting these things in the world that can hurt children, but it’s absolutely not the case. I thought, “Well, it’s maybe important to let my face be seen, let them look at me, let them hear me and just see me actually defend my book.”

I also knew that if I came in person, there would be much more media attention for the situation and for what’s going on across the country. As I said, I had already started hearing from people that this is not isolated to Central Bucks. It’s happening even in districts where they have a more lenient policy, and where educators and librarians actually have power and the ultimate right to decide about books. If they do decide to put a book back, sometimes librarians get besieged with these letters from angry parents. I just wanted to add my voice and let people know that there may be another way of looking at this issue.

It does seem like there are political motivations behind these school book challenges. But I also think that there are people who are swept up in it, who maybe don’t have the full picture and have not thought about it in all the ways that you can think about it. I thought if I showed up, I could convince some of those people who are just maybe not being fed all of the information correctly about what these books are and who is writing these books and what our intent is in writing these books; maybe I could do some good.

What did it feel like when you were actually there in the meeting?

Honestly, I was nervous. The thing about being an author is that people don’t normally come to your reading to tell you that they hate you and hate your book and will never read it. It was a new experience for me to fly into a hostile environment where I’m not being paid in any way and where I was maybe not welcome by parts of the community. I had also gotten some messages from people who knew the area who said, “You know, you really should consider hiring private security, you need to be alarmed.” I knew there had been a gun incident earlier at the same meeting. I really didn’t know how much I would be attacked, and how antagonistic people would be. I was afraid that I wouldn’t be given the chance to be heard.

In the end, I was grateful that I was treated with respect, and that I was heard. I really appreciated that. But I was also saddened by the degree of antagonism and division in Central Bucks. It was just so obvious. It just seems like people who, I think at heart have many of the same passions such as a great care for children, and a lot of passion about education, have settled on two sides of this divide. I thought that was such a pity and so sad.

I do think that there are many people who don’t need to be so divided. There is obviously a spectrum, as with anything. You have some people on really unreasonable ends of the spectrum. But I think that there are a lot of people in the middle that I hope can kind of find each other on this divisive issue.

What message do you hope that students will take from Girl In Translation?

For me, Girl In Translation is very much about how there’s a difference between the person we are on the outside and the person we are on the inside. Meaning that you can have someone who maybe doesn’t speak the language very well, isn’t well dressed, has a different skin color, comes from a different socio-economic class, and presents in a certain way in English, but underneath that surface, they can be a completely different person that you can hardly glimpse, because of that language and cultural barrier. My hope has always been that people reading Girl In Translation can walk away with a little bit more compassion for each other, and for people who are different from themselves.

I give talks around the world about my book, and almost everywhere I go, no matter how exclusive the community, someone comes up to me and whispers in my ear, “This was my life, or this was my mother’s or this was my brother in law’s and, but please don’t tell anyone.” So, there’s that kind of click of recognition, that feeling that you’ve been heard. I hope that will happen for some readers. It’s a book that I hope will connect people more.

Can you tell me a little about your newest book?

It’s called The Leftover Woman and it will be released this October. The book starts in China during the one-child policy when a young woman gives birth to a baby. She is told a few hours after birth that her baby has died and she grieves. But a few years later, she finds out that her daughter has not died. Her husband had actually given it away to a wealthy American couple for adoption, because the baby was a girl and he wanted to have a boy, which was not allowed if you already had a child under the one-child policy in China.

When the book opens, the birth mother has followed her daughter to New York City to try to get her baby back. The novel is told from two points of view, both the birth mother’s and the adoptive mother’s. The adoptive mother is flawed, but actually deeply loves her adoptive daughter.

Tune into The Signal podcast Wednesday for an interview with Jennifer Berkshire, author of A Wolf at the Schoolhouse Door: The Dismantling of Public Education and the Future of School. Listen on Apple, Podbean, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.