Oklahoma officials have petitioned the Supreme Court to hear an appeal on a case that challenges the nation’s first taxpayer-funded religious charter school. Should SCOTUS agree to hear the case and then decide in favor of the school, it could change how we do public education in Pennsylvania and the rest of this country.

The story of how we got to this point is a little policy-wonky, but it’s worth diving into because every step reveals the issues at stake.

How did this get started?

In 2022, the Archdiocese of Oklahoma City and the Diocese of Tulsa wanted to launch a charter school. Charter schools are taxpayer-funded, but privately owned schools even though the law establishing charters in Oklahoma prohibits spending taxpayer dollars on a religious organization. So the state board that oversees charter schools in Oklahoma asked the state’s attorney general if that restriction on religious charters might be overturned.

The AG at that time was John O’Connor. O’Connor was a Trump nominee for a United States district judge in 2018; the American Bar Association rated him “not qualified,” and his nomination was withdrawn. After Oklahoma’s previous attorney general resigned in May of 2021 over “personal matters,” Governor Stitt appointed O’Connor to the office. O’Connor ran for the office in 2022, and was narrowly defeated in the primary by Gentner Drummond (no Democrat ran for the office at all).

In a 15-page opinion issued December — after he had lost the election, but before he left office — O’Connor argued that in the wake of Trinity Lutheran, Espinoza, and Carson, he believed that SCOTUS would “very likely” find Oklahoma’s charter law restriction on nonsectarian or religious charters unconstitutional. Therefore, his opinion is that the state should no longer follow the law forbidding sectarian or religious charter schools.

Upon taking office, Drummond immediately withdrew O’Connor’s opinion, arguing that it “misuses the concept of religious liberty by employing it as a means to justify state-funded religion. If allowed to remain in force, I fear the opinion will be used as a basis for taxpayer-funded religious schools.”

Drummond, we should note, is no fuzzy-hearted liberal; he recently blamed the Biden-Harris administration for the terrorist plot thwarted in Oklahoma. His concern was that opening the door to taxpayer-funded religious schools would lead to a “slippery slope” down which would glide all manner of religious schools, including schools that Oklahoma taxpayers really wouldn’t want to fund.

The charter board, whose members are appointed by Christianist conservative governor Kevin Stitt, approved the charter school anyway.

What is this school?

The church proposed launching a cyber charter, St. Isidore of Seville Catholic Virtual School, named for a 6th Century Catholic bishop and scholar, who is patron saint of the internet (a “saint who can help us find what we need as well as protect us from the darker side of the World Wide Web”).

There is nothing stealthy about the religious nature of the school. An AP report notes, “Archdiocese officials have been unequivocal that the school will promote the Catholic faith and operate according to church doctrine, including its views on sexual orientation and gender identity.”

This does raise some tangential questions: how much do sexual orientation and gender identity matter when students are primarily just fingers on a keyboard?

Reactions

Governor Stitt hailed it as “a win for religious liberty and education freedom in our great state.” His State Superintendent Ryan Walters not only supported the school, but took partial credit for their decision:

This decision reflects months of hard work, and more importantly, the will of the people of Oklahoma. I encouraged the board to approve this monumental decision, and now the U.S.’s first religious charter school will be welcomed by my administration.

Walters is Oklahoma’s far-right education leader who has walked into a string of controversies, most recently mandating the use of a King James Bible in every classroom.

READ: Pennsylvania Taxpayers Are Subsidizing Discrimination at Private and Religious Voucher Schools

Opposition came from at least one surprising source. Nina Rees, the President and CEO of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, disagreed with the decision. Arguing that charter schools are meant to be public schools and therefore “must be non-sectarian.” Rees says, “The Archdiocese of Oklahoma City is trying to make charter schools into something they are not.”

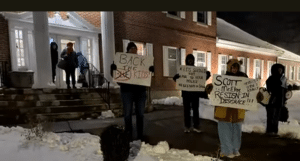

A group of parents, faith leaders, and educators filed a lawsuit shortly thereafter. The Rev. Lori Walke, senior minister at Mayflower Congregational Church in Oklahoma City and one of the plaintiffs in the case, said, “Creating a religious public charter school is not religious freedom… when we entangle religious schools to the government … we endanger religious freedom for all of us.”

AG Drummond called the decision “contrary to Oklahoma law and not in the best interests of taxpayers.” And to underline the point, he has sued the virtual charter board as well as members of the statewide charter board.

His position remained consistent. “There is no religious freedom in compelling Oklahomans to fund religions that may violate their own deeply held beliefs,” Drummond said. “The framers of the U.S. Constitution and those who drafted Oklahoma’s Constitution clearly understood how best to protect religious freedom: by preventing the State from sponsoring any religion at all.”

St. Isidore loses the first round

The lawsuit itself minced no words.

The Oklahoma Attorney General is compelled, as chief law officer of the State, to file this original action to repudiate the Oklahoma Statewide Virtual Charter School Board’s (“the Board”) Members’ intentional violation of their oath of office and disregard for the clear and unambiguous provisions of the Oklahoma Constitution

The suit seeks “to undo the unlawful sponsorship” of St. Isidore’s. The suit says that the AG “is duty bound to file this original action to protect religious liberty and prevent the type of state- funded religion that Oklahoma’s constitutional framers and the founders of our country sought to prevent.”

Make no mistake, if the Catholic Church were permitted to have a public virtual charter school, a reckoning will follow in which this State will be faced with the unprecedented quandary of processing requests to directly fund all petitioning sectarian groups….

In June of 2024, Oklahoma’s Supreme Court sided with Drummond. The court found that the charter school was in clear violation of the state constitution and, because it is a public school, must follow the state’s rules. Wrote the court:

The State’s establishment of a religious charter school violates Oklahoma statutes Oklahoma Constitution, and the Establishment Clause. St. Isidore cannot justify existence by invoking Free Exercise rights as religious entity. St. Isidore came into existence through its charter with the State and will function as a component of the state’s public school system. The case turns on the State’s contracted-for religious teachings and activities through a new public charter school, not the State’s exclusion of a religious entity.

READ: Project 2025 Wants to End Public Education As We Know It

In other words, charters can’t invoke the rights of a private organization to Free Exercise, because they are not private organizations, but part of the state.

It’s this ruling that the Oklahoma State Charter Board would like SCOTUS to overturn. Their goal is for a Catholic school to be funded with taxpayer dollars while remaining free to ignore any state rules and regulations, especially those involving discrimination. In other words, they would like taxpayers to fund a school that teaches that Catholicism is the only true religion and which can expel students for being gay.

“But that can’t be legal,” you may be thinking. Well…

A quick Constitutional sidebar

The First Amendment has two clauses that exist in tension with each other. The Establishment Clause says the government can’t back or promote any religion; the Exercise Clause says the government can’t interfere with anyone’s religious activities. They are so closely intertwined that they are two parts of a single sentence:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.

Public schools, as state actors, are considered part of the government. For a long time, especially when it came to schools, the courts leaned toward the Establishment Clause, barring anything that could be seen as a school’s endorsement of religion (like, for instance, a Christian prayer delivered by school district authorities at official school functions).

But that was then.

What the Supreme Court has been up to

The petition to SCOTUS and O’Connor’s original opinion both cite three cases: Trinity Lutheran, Espinoza, and Carson. These three cases mark an erosion of the wall between church and state.

In Trinity Lutheran (2017) the court found public funds could be used by a church for ordinary secular purposes, like paving a parking lot.

In Espinoza (2020), the court found that public funds cannot be denied a private school just because it is run by a church.

Carson (2022) established that the state couldn’t deny a private school funding even if that school openly and clearly discriminated on the basis of religion or LGBTQ issues.

Noah Feldman, a Harvard law professor and former clerk for Justice David Souter, explained the significance of Trinity Lutheran:

It’s the first time the court has used the free exercise clause of the Constitution to require a direct transfer of taxpayers’ money to a church. In other words, the free exercise clause has trumped the establishment clause, which was created precisely to stop government money going to religious purposes.

Justice Sotomayor’s dissent further nails the significance of the decision:

After assuming away an Establishment Clause violation, the Court revolutionized Free Exercise doctrine by equating a State’s decision not to fund a religious organization with presumptively unconstitutional discrimination on the basis of religious status.

These principles were extended with each following decision. The court has declared that it is discriminatory not to give religious organizations taxpayer dollars, that these groups cannot freely exercise their religion unless they are paid with taxpayer dollars and allowed to discriminate as they wish.

A fourth case included in the petition is Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the case in which a high school football coach was let go after repeatedly holding large public prayers on the fifty yard line at the end of games while still on duty. SCOTUS held that he was simply exercising his personal, private religious beliefs. It was a conclusion reached by deliberately ignoring the facts of the case, but it further established that for school, free exercise trumps the Establishment Clause.

After SCOTUS required the district to give him back his job, Coach Kennedy, who had built a career on the religious liberty conservative speaking circuit, coached exactly one game, then resigned. Each of these cases, and many others like them (Hobby Lobby, the wedding cake case, etc) are about rewriting law via court decisions, not about the actual concerns of the people in whose name they are brought.

What do the petitioners want?

The petition asks the court to settle two questions.

First, is the charter school a state actor? The petitioners want the answer to be no, because then they are not bound by the same state rules and regulations that any public school.

After decades of charter schools, you would think this question would have been answered, but it has not. Charter schools continue to exist in a murky middle world where they are either public or private schools depending on what best suits their purposes. In states that also have school vouchers, the “public” label is particularly important, because it’s about the only marketing edge they have over the private voucher-accepting competition. But the “public” label comes with state regulation, which charter operators would prefer to avoid.

The Supreme Court Justices had a chance to rule on this question just last year in Peltier, a case in which a charter school invoked its “not a state actor” status to justify a sexist, Title IX-violating dress code. But the court declined to hear the appeal.

Second, the petitioners want to see the reasoning of the three cases cited to cover this situation, following Chief Justice John Roberts’ reasoning from Carson:

In particular, we have repeatedly held that a State violates the Free Exercise Clause when it excludes religious observers from otherwise available public benefits.

INTERVIEW: ‘Christian Nationalism Is on the March’ and Is a Threat to Inclusive, Multiracial Democracy

In his dissent on Carson, Justice Breyer speculated on where this reasoning may take us:

What happens once “may” becomes “must”? Does that transformation mean that a school district that pays for public schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to send their children to religious schools? Does it mean that school districts that give vouchers for use at charter schools must pay equivalent funds to parents who wish to give their children a religious education?

The petitioners are hoping that the answer is, in fact, yes, yes it does.

The board is represented by the Alliance Defending Freedom, the Christian legal advocacy firm that drafted the Mississippi anti-abortion law that led to the Dobbs decision.

What happens next?

The very next step in the process will be the court’s decision to either take up the petition or leave it alone. If they leave it alone, the nation’s first religious charter school will be done, a school that almost happened.

If the court takes up the petition — well, O’Connor is not wrong in thinking that this court may be poised to kick another hole in the wall between church and state (and getting to SCOTUS for that purpose may have been the point all along). If the rule becomes that taxpayers in all states can be compelled to pay taxes to support a religious school, there are a handful of predictable outcomes.

First, of course, is a proliferation of charter schools operated by multiple religions. Expect the Satanic Temple, which has specialized in trolling “religious liberty” laws, to be at the front of the line. Drummond’s fear that taxpayers will have to fund all manner of religious charters with which they disagree will become reality. If my tiny sect of frog-worshippers wants to start a charter school, is it religious discrimination for the state not to give me the money to realize our dream?

In states where the religious charter sector explodes, the state will either have to try to fund multiple school districts with the same old funds, or they will have to raise taxes. Where states already have a large voucher program, this may not matter much — charter and voucher schools will be almost indistinguishable. But in Pennsylvania, where vouchers are a more modest sector, an explosion of religious charters could put a major strain on funding.

READ: The Christian Right’s Playbook to Elect Donald Trump in November

States will have another choice. The reading of the law says if taxpayers fund secular charters, they must also fund religious charters, so another solution is to simply kill off charters entirely.

The other option is for the state to empower some government board to determine which charter-sponsoring religions are “legitimate.” It’s a frightening prospect, but we’ve already seen it in places like Florida, where Governor Ron DeSantis has shown, in response to the school chaplain program, he’s comfortable declaring what is and is not a real religion. All one needs to do is imagine an alternate reality in which Pennsylvania is led by Governor Doug Mastriano to see how terribly wrong this could go.

Right now, there are states (like Florida) where taxpayers fund extreme religious schools and states (like Pennsylvania) where such funding is minimal. If SCOTUS takes this case and finds in favor of St. Isidore, all taxpayers will foot the bill for indoctrination, whether they or their elected representatives like it or not.

When you mix religion and politics, you get politics. Let’s hope that SCOTUS decides not to pick up this particular mixing bowl.