On August 22, 1964, Fannie Lou Hamer captivated the American public as she testified at the DNC about the suffering she endured for trying to register to vote two years earlier in Mississippi. “We was met in Indianola by Mississippi men,” she recalled, “highway patrolmens, and they only allowed two of us in to take the literacy test at the time.” After only a fraction of the eighteen members of her group were permitted to take the test, which was required by Mississippi law and practice before Black Mississippians could register to vote, “we was held up by the City Police and the State Highway Patrolmen and carried back to Indianola, where the bus driver was charged that day with driving a bus the wrong color.” Hamer explained that she was subsequently fired, shot at, beaten, and jailed for trying to register to vote in Mississippi. An iconic and groundbreaking moment in American history, her powerful testimony challenged the all-white Mississippi delegation to the convention and signaled the advent of a radical form of Black political organizing on the national stage.

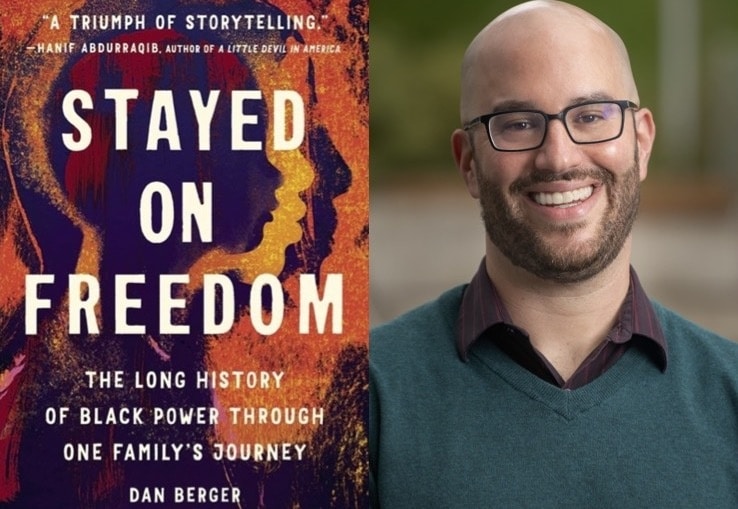

Dan Berger’s Stayed on Freedom: The Long History of Black Power Through One Family’s Journey tells the story of this ongoing struggle for justice and equality through the lens of ground-level activists. It shows how each of us have a role to play in creating better worlds premised on human potential rather than plunder; joy and community rather than state violence and subordination; health and happiness rather than extraction and coercion.

Amid renewed efforts to suppress and disenfranchise Black voters as well as a wave of impossible white conservative lies about “millions of people pour[ing] into our country” to cast ballots, Berger’s Stayed on Freedom provides a crucial window into the ground-level work of liberation and democracy in the Black Power movement. Readers (especially white ones) might be surprised by the association of the phrase Black Power with democracy, a result of decades of intentional misinformation about the movement and the goal of Black radical politics more broadly. However, as Berger carefully explains, the phrase and the movement were “a response to the feeling of inferiority and helplessness Black people expressed under segregation” (9). The term does not and has never represented a “reverse racism”— an inversion of white power slogans and ideology touted by white supremacists and neoNazis – Donald Trump’s “very fine people.” It poses a reassertion of human dignity akin to saying the phrase “Black Lives Matter,” similarly denounced by racists today.

Celebrating and even demanding Black Power — within the context of Jim Crow — asserted a level of worth for Black Americans that organizers identified as lacking, one that staked a claim to equality denied them by the state, not just in the South, but nationwide. As Malcolm X famously put it, “I’m speaking as a victim of this American system. And I see America through the eyes of the victim. I don’t see any American dream; I see an American nightmare.” The state and its institutions had been crafted and operated at the expense of Black Americans. The segregated schools, neighborhoods, and institutions not only stole public services from Black Americans rightfully theirs by virtue of their citizenship, tax dollars, and humanity, but also took wealth, opportunities, and representation from them through workplace discrimination and disenfranchisement. Just as the so-called “Three-Fifths Compromise” had counted disenfranchised Black Americans for white political power, so too did the state laws suppressing Black voting beginning in the 1890s, laws that remained in effect until 1965. It was, indeed, an American nightmare.

As Malcolm X explained, the American nightmare was no accident or misunderstanding. It resulted from policies carefully designed by white elites at every level of American government—a system of plunder. The government could pursue its interests in other countries, he noted, but refused to act on those of its Black citizens, because the state reflected the material interests of elites. He observed:

And concerning anything in this society involved in helping Negroes, the federal government shows an inability to function. But it can function in South Vietnam, in the Congo, in Berlin, and in other places where it has no business. But it can’t function in Mississippi.

While the U.S. participated in literal colonial wars—and still holds colonies today—it treated Black Americans as colonial subjects, drafting them into its wars of empire while depriving them of the rights for which they allegedly fought overseas.

Thus, for Black Power activists, demanding and creating a sense of worth, value, and power was and remains a necessary response to the anti-Blackness that formed the governing ideology of the American state and its chronic “inability to function” to protect and serve Black Americans. If this is news to you—and our education and media landscape makes that a likelihood—Stayed on Freedom provides an excellent window into this very different way of understanding our world.

The large cast of freedom organizers, “everyday people” whose work Berger engages, often briefly, revolve around the more detailed stories of Zoharah Simmons (born Gwen Robinson) and Michael Simmons. It was their Atlanta Project of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) that laid the intellectual foundation for Black Power. Born of the working class, neighborhood-level organizing and politics that the group launched in Atlanta, particularly among the laborers and domestics commuting through Five Points, their “Black Consciousness Paper” challenged the national leadership of SNCC to do more community-oriented, world-building work. They registered voters, pooled resources, created schools, and helped build a sense of community in the localities where they operated. They desired “a Black organization (devoid of cultism) [to] be projected to our people so that it can be demonstrated that such organizations are viable.” Doing this work, from the perspective of the Atlanta Project, would promote the dignity and welfare of the everyday people with whom they lived, worked, and organized.

READ: Racist Mass Violence Isn’t Incidental To White Conservatism—It Is Its Defining Feature

By merging race and class politics with internationalism, the “Black Consciousness Paper” argued that Black Americans were “victims of domestic colonialism” (129). White employers had stolen Black labor and suppressed Black wages for generations. They had historically written into law and solidified in practice that generations of Black Americans couldn’t own property, possess firearms, testify in court, or vote. They made it so that only a handful of jobs were open to the overwhelming majority of Black Americans—manual and agricultural labor, domestic and food work—and had then written national laws like the Social Security Act of 1935 to make sure that those working these jobs were ineligible for public benefits. Thus, the Atlanta Project concluded, “we reject the American Dream as defined by white people and must work to construct an American reality defined by Afro-Americans” (129).

White Americans still had an important role to play in the Black Power vision, as Berger notes, “to develop an anti-racist constituency in white communities” (129). While this insistence has been cast by white supremacists themselves as discriminatory, its goals for the Atlanta Project were strategic. If anti-Blackness represented a central tenet of the American religion, white Americans acting in their own communities as, say, teachers, must play a substantial role in combating the white supremacist ideology at its source: the white community. Moreover, if the goal of the “Black Consciousness Paper” was to promote racial pride, organization, and consciousness among Black Americans, what part would white Americans actually be able to play in that? As the paper explained, “white people coming into the Movement cannot relate to the ‘Nitty Gritty,’ cannot relate to the experience that brought such a word into being, cannot relate to chitterlings, hog’s head cheese, pig feet, ham hocks, and cannot relate to slavery, because these things are not part of their experience” (130). Black Americans had unique sets of experiences because of the history of racism in the United States. While white organizers could and must contribute to the struggle against the racist institutions at the heart of that dynamic, they necessarily had to do so outside of those experience-informed Black spaces.

Berger’s framing of Robinson’s and Simmons’ experiences shows, time and again, that agents of the state will not serve the interests of its citizens over those of the rich and powerful (and racist). Whether it’s the sheriff who held Robinson at gunpoint for trying to sit in a segregated diner (78) or local police who arrested Simmons for filing a police report (106), the book is replete with examples of the lawlessness of the agents of the ruling class. There’s even an “affable” FBI agent who promised Simmons he would protect civil rights workers only to call him a “black sonofabitch” and assist in his arrest by racist local police (107). The experience of civil rights workers like Robinson and Simmons, as Berger shows, illustrate that those in power pursue their own interests at the expense of the vulnerable. The way forward towards liberation, then, lies in the organizing, mutual aid, and community self-defense that actually creates the world activists demand from the state and its institutions. It requires the hard work of finding volunteers, raising money, identifying and mobilizing local resources and leaders, and building a sense of community that surpasses the indignities of discrimination and oppression.

One of the themes that will stand out for readers, and that we should all carefully consider, is that of nonviolence. Both Robinson and Simmons began their work with SNCC, whose commitment to nonviolence was written into its name. The organization might conjure images of its famous chairman, John Lewis, being beaten on Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday. While SNCC maintained a commitment to nonviolence, it also employed armed self defense, viewing the two as working in tandem. We can see the relationship between the two clearly in the person of Mrs. Spinks, the retired meat worker who housed Robinson and her fellow activists during Freedom Summer. Amid escalating threats, beatings, arrests, and fire bombings carried out by white locals, “Spinks would keep vigil on her porch with a shotgun.” She viewed this not only as an act of survival, but a contribution to the movement, telling her “they might get me… but I’m going to get one or two of them first. You all can sleep, because I’m watching” (77). Unprosecuted, unidirectional white violence, often at the hands of police themselves, was a well-known tactic white supremacists had used for a century to undermine Black rights. Careful organizing and public pressure campaigns could help with this, but the constant stream of violence took its toll on civil rights workers, even when they survived. Robinson eventually had to close the SNCC office she had founded in Laurel, Mississippi after it was repeatedly burned down, due to the toll on her mental state (99-102).

The larger issue worth considering here is what constitutes nonviolence and the role it plays relative to systems of power. The horrible truth is that Black activists like Robinson and Simmons already experienced a state of chronic vigilante and state violence. Whether or not they chose to arm themselves, they would inevitably be subject to violence. It was already there. There was no prospect of nonviolence within that system—the only question was whether or not they would defend themselves. Again, Malcolm X provides important context for that decision:

The only people in this country who are asked to be nonviolent are black people. I’ve never heard anybody go to the Ku Klux Klan and teach them nonviolence, or to the Birch society and other right-wing elements. Nonviolence is only preached to black Americans and… I believe that we should protect ourselves by any means necessary when we are attacked by racists.

This dynamic remains a fundamental problem with how the American public talks about movements for equality today. The existing violence of the racial state and its vigilante wing is hidden from view, while protestors and activists are termed violent and labeled as terrorists for being attacked by this existing regime of violence. It is not so much a question of whether self-defense does or doesn’t represent a viable alternative, since the totalizing violence of the state and its juridical means of repression cannot be meaningfully countered, even when it raises the costs for the regime. But to demand nonviolence as radical passivity within an existing system of suppressionist violence is to concede (and even require) defeat by that system.

If the centrality of violence to ongoing systems of repression causes us discomfort today—and it should—it also reveals the importance of the Black Power movement and its articulation of liberation today. Black Power activists envisioned communities defined by love, self-respect, and human potential. They presented white Americans (and others) the opportunity to create freedom in a meaningful sense grounded in human dignity and worth rather than in defining rights or Americanness as a negation of Blackness.

What Stayed on Freedom offers is both a window into and a bridge towards a better world, one that is ours—all of ours—for the taking.

********

I hope you will set aside a few minutes (or some time later) to take one of the literacy tests given to Black Americans as a barrier for registering to vote, made available here by the Jim Crow Museum. When I’ve assigned the test during classes, students overwhelmingly share how it clarifies, as just one of the many obstacles placed in front of Black voters during my parents’ lifetime, how racial oppression was woven into ostensibly colorblind laws and institutions. The divergent, discriminatory worlds these practices created directly impacted me (and probably you too) in some ways that are obvious and others that require further reflection.