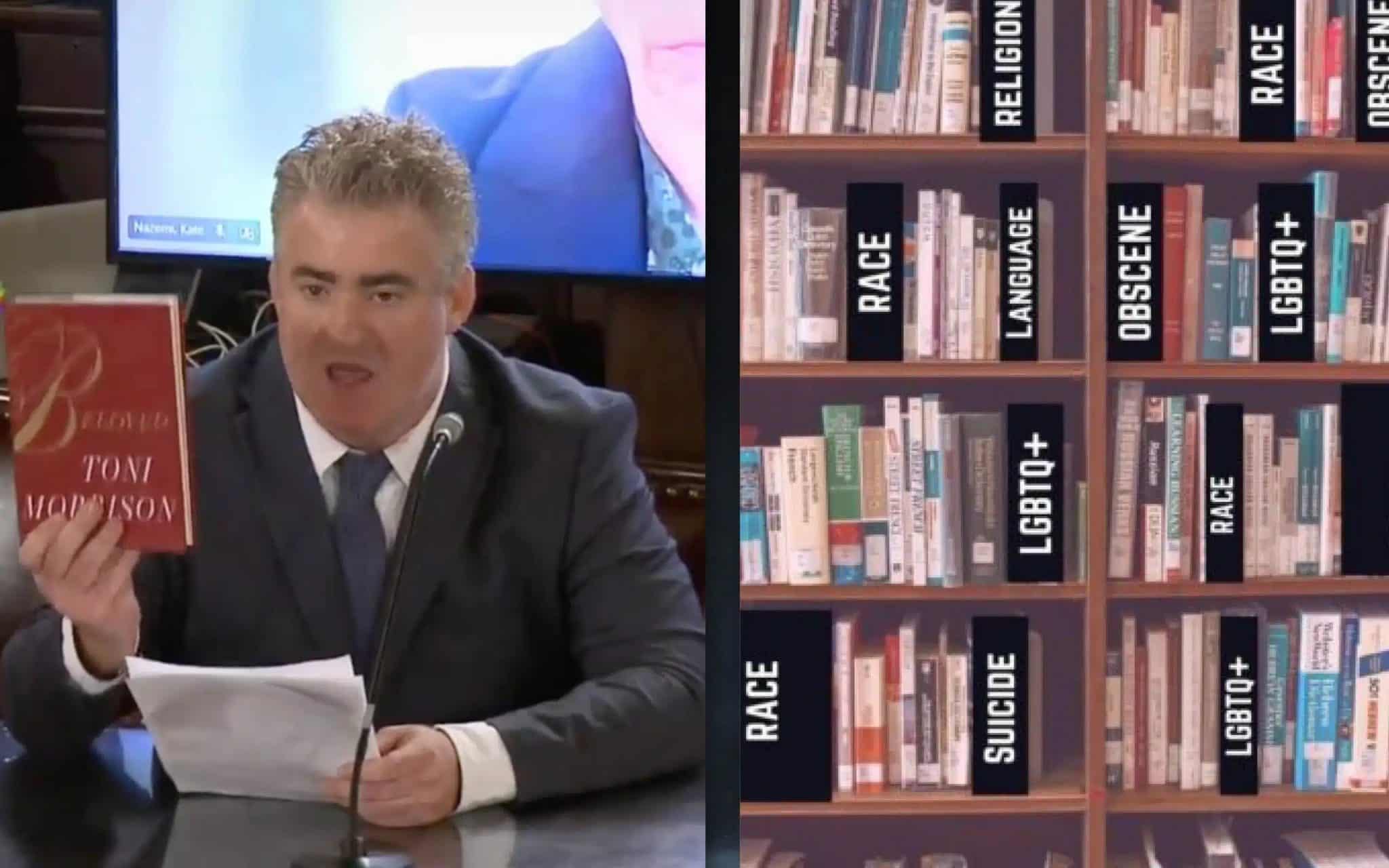

Three years ago, I sat in a Pennridge school board meeting and listened as our directors claimed that “pornography” was rampant within our high school library. The first book they targeted was Allegedly by Tiffany D. Jackson. But the excerpt they read aloud that night wasn’t even real, it was cobbled together from bits and pieces of different chapters to make the novel sound obscene. Within days, that book and dozens more had vanished from high school library shelves. This was just the beginning.

This year, as Banned Books Week reminds us of the ongoing struggle for intellectual freedom, I cannot help but reflect on how local episodes like ours became part of a much larger movement. What began in small suburban school districts has grown into a larger coordinated effort, stretching from public libraries to museums, and even national institutions.

A school library is a place of voluntary exploration. No one is forced to pick up a book. But when a student chooses Looking for Alaska by John Green, they just might be trying to understand grief, loss, or where they fit in the world.

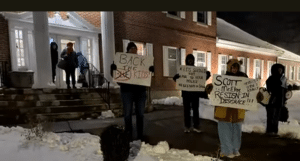

That is why I was struck by former Pennridge school board director Jonathan Russell’s recent claim in this publication suggesting that removing books from shelves does not amount to banning, since students could still find them elsewhere. Russell, who lost his seat in the last election but is now seeking to return, misses the point. For many students, the school library is their only access to books. It is also the place where professional librarians help young people discover age-appropriate material that matches their reading level and interests. When politicians order books off the shelves, they aren’t protecting kids—they’re silencing voices, narrowing choices, and undermining the very purpose of a public education.

When Democrats won a one-vote majority on the board, they replaced the leadership that had secretly planned and executed the Pennridge book purge. That effort included doctored public records, which a judge later ruled showed the district had “acted in bad faith” and carried out a cover-up. Under new leadership, books like Looking for Alaska, Beloved, Allegedly, and Sold were restored, along with a transparent and legal process for future book challenges.

Pennridge already has a system that allows parents to block access to books they consider inappropriate for their own children. That is entirely reasonable. What is not reasonable is imposing those personal views on other people’s children. Many of the most aggressive challenges now come from people without children in the district, often armed with lists from BookLooks.org, a website that rips passages out of context to stir outrage.

The case of Sold by Patricia McCormick is especially telling. The young adult novel follows Lakshmi, a 13-year-old Nepali girl trafficked into prostitution. The book is a powerful tool for teaching young readers about one of the world’s most devastating crimes. Yet in the name of “protecting children,” the previous board removed it from the Pennridge High School library. By eliminating any literature that addresses sexuality, they erased a story that could help students recognize the warning signs of exploitation and abuse.

Equally troubling is the rhetoric used to defend bans. Those who support censorship often smear opponents as “groomers.” The logic is inverted. They attack those of us who defend books that teach consent, explain manipulation, and give survivors the courage to speak up. In truth, predators benefit when young people remain uninformed. Banning these books makes that outcome more likely.

The fight has already spread beyond our schools. In Telford, Councilman Robert Jacobus repeatedly tried to strip funding from the Indian Valley Public Library because of LGBTQ-themed books that were not even in the children’s section. Across Pennsylvania, the Independence Law Center, a right-wing Christian legal group, has been drafting policies (often secretly) for districts to replicate censorship strategies.

READ: The Independence Law Center Seeks to Impose its Biblical Worldview on Pennsylvania School Districts

Nationally, the same pattern continues. The Trump administration issued directives targeting the Smithsonian, demanding that exhibits on slavery be removed because they were considered “divisive.” Another executive order titled “Restoring Freedom of Speech” claimed to protect expression while actually empowering the government to punish dissent. What began as the removal of novels from school libraries has escalated into attempts to rewrite how Americans understand history.

History shows that censorship grows if it is not resisted. Give up one book, and demands will multiply … That is why Banned Books Week is not simply symbolic. It is a reminder that the freedom to read depends not just on vigilance, but action.

History shows that censorship grows if it is not resisted. Give up one book, and demands will multiply. Allow the purge of one school library, and the entire district becomes a target. The same logic applies to public libraries and museums. The pattern is already evident.

That is why Banned Books Week is not simply symbolic. It is a reminder that the freedom to read depends not just on vigilance, but action. Communities must attend board meetings, support libraries under attack, and participate in every election.

READ: Bucks County Testimony In Harrisburg Highlights Need For Legislation To Stop Book Bans

The right to read is not about forcing ideas on anyone. It is about preserving spaces where people can freely seek knowledge and understanding. Students deserve books that reflect the full complexity of human experience. They deserve stories that might save their lives, broaden their empathy, or help them feel less alone.

The censors are organized, well-funded, and persistent. Defending intellectual freedom requires the same commitment. The books they fear most are the very ones our children need most.