Union leaders met in Hershey this week for the Pennsylvania Conference of Teamsters annual convention.

Some of Pennsylvania’s most powerful politicians, like Gov. Josh Shapiro, state House Speaker Joanna McClinton (D-Philadelphia) and U.S. Rep. Brian Fitzpatrick (R-1st District) made appearances to support the trade union, which is one of the largest in the world and claims 1.3 million members in a wide variety of occupations.

Teamsters leaders at the gathering discussed their goals for the year, and broadly outlined strategies in areas from workplace organizing to making political endorsements.

But many who spoke had a particular target in their sights: Amazon.

The union has been at odds with the company for years over working conditions for Amazon drivers and warehouse staff. And they’ve fought Amazon’s decision to classify some workers, including drivers, as independent contractors. That classification lets the company off the hook for providing certain benefits, like health insurance, and guarantees, like minimum wage, the union argues.

Though Amazon says their “delivery service partners,” which the company describes as small and medium-sized businesses that they contract to run their delivery routes, “provide health care coverage that meets or exceeds federal standards for affordability and minimum value.”

For years, Teamsters have pushed to organize the company’s workforce. The union says it has organized 10,000 warehouse workers and drivers. That includes employees at a distribution center in New York that Teamsters say has over 5,000 employees and voted to join them in 2024. Amazon, however says they don’t recognize any unions at their facilities and that the Teamsters have never brought an election. Moreover, they say drivers, unionized or not, aren’t their employees.

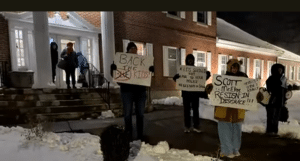

The feud between the company and union reached a boiling point during the last holiday season, when Teamsters urged Amazon employees at numerous facilities to strike and formed picket lines at other facilities, including in Pennsylvania. The union said the picket was over the company’s refusal to bargain with the group.

Speakers at the Hershey conference said that action was just the opening salvo.

“This is the beginning of a war with Amazon,” said William Hamilton, president of the Pennsylvania Conference of Teamsters, which represents around 95,000 workers in warehouse, transport and other industries. “Amazon started the war on workers because they’ve continually attacked workers across this country and mistreated them. They created this environment of unsafe conditions, of low pay, of doing things to people that people on the outside would never even consider to be something an employer should be doing.”

Amazon has come under the scrutiny of lawmakers, regulators and advocacy groups in the past over allegations of creating unsafe and unsanitary work conditions. For example, The Guardian, The Intercept and other outlets have reported that Amazon’s aggressive tracking of worker productivity lead some drivers and warehouse staff to skip bathroom and food breaks.

Eileen Hards, a spokesperson for Amazon, said in an email that “Amazon already offers what many unions are requesting: safe and inclusive workplaces, competitive pay, health benefits on day one and opportunities for career growth.”

The company also said that employees are encouraged to take breaks when needed, and that their delivery app provides suggestions for places drivers can stop and use a restroom.

Hards added that Amazon workers can choose to join unions if they want, but that Teamsters’ efforts to unionize employees have been coercive.

“The truth is that the Teamsters have actively threatened, intimidated and attempted to coerce Amazon employees and third-party drivers to join them, which is illegal and is the subject of multiple pending unfair labor practice charges against the union,” Hards said.

Teamsters, on the other hand, say Amazon has fought their workers’ efforts to organize and join them.

And Teamsters have also been fighting the company through courts and regulators. Last week, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) issued a complaint saying that Amazon failed to come to the bargaining table with employees of a distribution center in San Francisco after more than 100 voted to join a Teamsters-affiliated union.

“Amazon started the war on workers because they’ve continually attacked workers across this country and mistreated them. They created this environment of unsafe conditions, of low pay, of doing things to people that people on the outside would never even consider to be something an employer should be doing.”

That follows another victory last year when NLRB prosecutors sided with Teamsters, who were calling for Amazon delivery drivers in Palmdale, California, to be classified as “joint employees” instead of independent contractors. The ruling is not final, and Amazon says it will be reviewed by an administrative law judge.

Still, Randy Korgan, the national director of the Teamsters’ Amazon division, said the battle must be waged on the ground by workers, instead of focusing on courts and state capitols.

“It’s been multiple decades since that system has truly done what it’s supposed to do, which is protect workers in an expeditious way,” Korgan told attendees at the Pennsylvania conference. “What we’re doing is we’re building committees. We’re educating workers and we’re getting them to understand that you’re not going to get your employer to recognize anything until you shut it down.”

Korgan claimed that the union organized nearly 10,000 Amazon workers in 2024 alone. He said that wasn’t done in a “traditional setting.” Instead he and others encouraged workers to stage walkouts and “take direct action.” That number includes drivers, who Amazon says are independent contractors.

It’s a small fraction of the roughly 750,000 warehouse workers and 210,000 drivers an Amazon spokesperson estimated the company employs or contracts in the U.S.. But the company says it isn’t true.

“For more than a year now, the Teamsters have continued to intentionally mislead the public – claiming that they represent ‘thousands of Amazon employees and drivers,’” Hards said. “They don’t, and this is another attempt to push a false narrative.”

Liana Dalton, an organizer for the International Brotherhood of Teamsters’ Amazon division said that organizing needs to be continued in Pennsylvania, where she hopes to see more Amazon facilities and drivers unionize, and build capacity for a potential strike. She said she’s heard from many who were inspired by the strike last winter, some of whom went to New York to join a picket line.

READ: 8 Ways States Can Fight Inequality and Build Worker Power

“We’ve gotta build this and we’ve gotta scale it, so that we shut down the entire market in these key regions,” Dalton said.

Amazon also came up repeatedly in discussions of the union’s political goals.

Thomas Doyle, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters’ state program director, said the union is also pushing bills in state legislatures around the country in the hopes of passing laws to improve conditions for Amazon warehouse workers.

Doyle said warehouse workers at Amazon are injured at higher rates than many companies in the sector. A bill the union is pushing around the country would require warehouses to disclose productivity quotas to their workforce. Doyle said that Amazon has not disclosed those in some circumstances, leading to workers rushing and increasing the potential for injury.

“In [typical] warehouses, we understand there are productivity quotas, but our workers are made aware of what they’re being measured against,” Doyle said. “This bill would mandate that a company has to make their workers aware of what they’re being measured against. So by eliminating that invisible clock, workers will be able to pace themself in a safer manner.”

Doyle said that bills requiring disclosure of productivity quotas have already passed in five states: California, New York, Minnesota, Washington and Oregon. And he’s hoping Pennsylvania will follow suit.

Hards, the Amazon spokesperson, said in an email the data pointing to Amazon warehouses being more unsafe than others is misleading.

“Since 2019 our recordable incident and lost time rates have improved by 31% and 76.5% respectively in the United States and 34% and 65% globally,” she wrote. “But, we’re not satisfied and we won’t be until we’re best in class.”

The company also said that it does not implement productivity quotas for warehouse workers.

Doyle also said the Teamsters advocacy arm will be lobbying for other legislation. Those would require human supervision in commercially used autonomous vehicles; require companies provide certain protections for workers exposed to extreme temperatures; and ban mandatory “captive audience meetings” discussing either religion or politics, which would be defined to include discussions of unionization. Such meetings are sometimes used by employers to disparage unionization efforts during work hours.

Pennsylvania Capital-Star, where this article was originally published, is part of States Newsroom, a network of news bureaus supported by grants and a coalition of donors as a 501c(3) public charity. Follow Pennsylvania Capital-Star on Facebook and Twitter.