This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Sheriffs walk a thin line between law and legend. Throughout rural America, sheriffs oversee most of law enforcement. Yet in the American cultural imagination, sheriffs are also the subjects of tall tales or gossip, from Western figures like Pat Garrett, Bat Masterson, Virgil Earp and John Slaughter to their fictional counterparts in Mayberry’s folksy Andy Taylor—or rather, Andy Griffith. With sheriffs, the mythmakers and the myths often get confused.

Today’s constitutional sheriff is no exception. Portraying themselves as living emblems of the law, these sheriffs claim sweeping powers constrained only by the county line and their singular reading of the United States Constitution. In asserting their authority over federal and state governments, with a duty to disregard laws they see as unconstitutional, constitutional sheriffs play a critical role nourishing the most serious threat to American democracy since the Civil War.

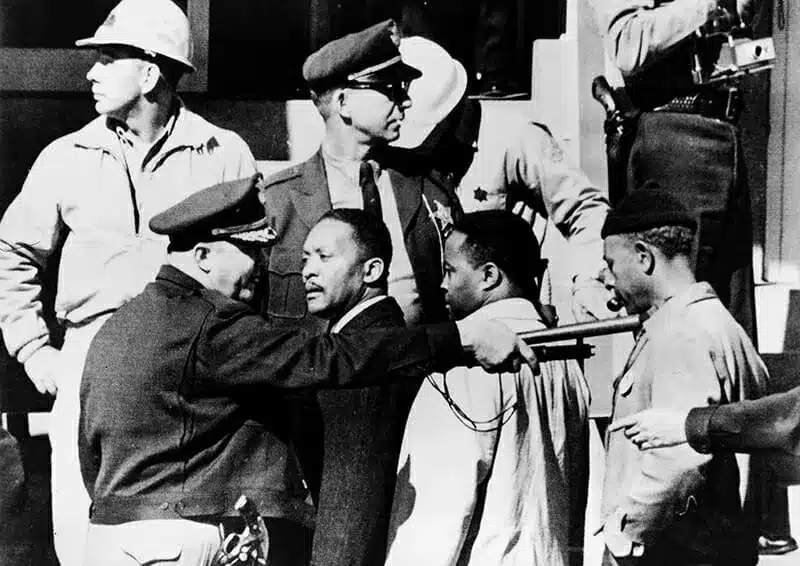

Former Arizona sheriff Richard Mack speaks at a pro-gun rally near the Washington Monument in 2010. As sheriff, Mack won a Supreme Court decision weakening the background check provisions of the Brady law. (Jim West, Alamy)

The most significant proponent of the constitutional sheriff movement is Richard Mack, the one-time sheriff of Graham County, Arizona. He founded the Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association, has served on the board of the Oath Keepers and has repeatedly invoked the sheriff as a mythic figure. In one telling, Mack argues that had there been a constitutional sheriff (a thinly-veiled version of himself) in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, that sheriff would have defied segregation laws to protect icons of civil rights like Rosa Parks. At Tea Party rallies, Mack fantasized Parks as an avatar of his favorite right-wing causes defying federal authority: “Today, that constitutional sheriff does the same for Rosa Parks the gun owner, or Rosa Parks the rancher, or Rosa Parks the landowner, or Rosa Parks the homeschooler, or Rosa Parks the tax protester.”

Mack’s myth-making is part of a long tradition of American revisionist history. Two books published days apart before the 2024 presidential election and a recent podcast series have shone valuable light on the role sheriffs play in that tradition.

Mack’s mythical development of the constitutional sheriff forms a central thread in The Highest Law in the Land: How the Unchecked Power of Sheriffs Threatens Democracy by journalist and attorney Jessica Pishko. The Power of the Badge: Sheriffs and Inequality in the United States, by political scientists Emily M. Farris and Mirya R. Holman, explores the wider landscape in which the constitutional sheriff has flourished. The podcast series, The Insurgence: Sheriffs, created and hosted by Cloee Cooper, research director at Political Research Associates traces the trajectory of Gale, Mack and the myth-making of other constitutional sheriffs to the January 6 insurrection and beyond.

With Trump back in office, constitutional sheriffs have been deafeningly silent on their favorite topic of government over-reach. And while they helped galvanize Trump’s law enforcement support, they’ve been far overshadowed by his reliance on Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and related support groups. Yet, the mythology of the constitutional sheriff and its relationship to the legal and political sources of their power reveals a great deal about the anti-liberal vision of America into which Trump has breathed more life than anyone since Lee’s surrender at Appomattox.

In contrast to Farris and Homan’s institutional historical focus on the office of the sheriff itself, Pishko and Cooper’s approach is more cultural, giving considerable attention to how and why sheriff myths appeal to people, particularly white rural conservatives.

Both open their account of events in rural Nevada. Pishko begins during the Covid era in Battle Mountain, a town of about 4,000 in Lander County, at a time when many Covid mitigation measures, such as statewide mask requirements, put extra distance between them and policymakers in the state’s capital in Reno more than 200 miles away.

In 2021, Lander County and neighboring Elko County each passed a resolution to become a “constitutional county,” stating that “any conduct contrary to the United States Constitution, Declaration of Independence, or the Bill of Rights will be dealt with as criminal activity.” The counties paid $2,500 for a lifetime membership to Mack’s Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association. Six Nevada sheriffs, about one-third of those in the state, showed up to celebrate this patriotic event. Headlined by Mack, he presented the county commissioners with a plaque to honor their membership, with security in the form of a militia, in the unlikely event that antifa or Black Lives Matter showed up ready to rumble.

“The Insurgence: Sheriffs,” a podcast series created and hosted by investigative reporter and Political Research Associates Research Director Cloee Cooper, and co-executive produced by Political Research Associates and Cuentero Productions.

Cooper focuses on another Nevada community: Minden, a “Sundown Town” in Douglas County where for generations an evening sundown siren signaled that non-whites could be arrested or physically assaulted if they stayed past sundown. Similar rules existed in towns throughout the nation, targeting Black and immigrant communities. The idea behind such sundown towns, Cooper says, was to “build out small localities where the sheriff was essentially an ally to various different far-right forces, some of which were explicitly racist.”

How racist? How much of an ally? A 1917 ordinance in Minden specifically required Native Americans to leave the town by 6:30 p.m. each day. It took until 1974 for the ordinance to be repealed, but its impact still lingers today. In 2020, a local rural library’s expression of support for Black Lives Matter prompted the Douglas County sheriff Dan Coverley to tell them, “do not feel the need to call 911 for help,” a preemptive dereliction of duty. (The sheriff’s office later rescinded the threat). Although Cooper doesn’t dwell on this event, it’s telling that a sheriff would feel empowered to unilaterally exile such an integral part of the community.

Cooper’s podcast shows how the militia movement and constitutional sheriffs share a common origin, so it’s natural to worry about them working hand-in-hand. “We actually get to listen to the people who were in 2020—during the racial justice uprising in this country—actually literally run out of town by militias that we later found were working actively with the county sheriff,” she says, providing a chilling reminder of “what that actual racial violence can look like.”

An older, deeper myth

Underlying the constitutional sheriff myth is an older and deeper one: the sheriff, in Pishko’s words, as “a chivalrous knight” who embodies the people’s will and protects them against all outside forces.

In one sense, sheriffs uphold the people’s will as elected officials. But as Farris and Holman show, this could hardly be further from the truth. The office is a feudal remnant in democratic drag, they argue, virtually immune to accountability, serving wealthy elite interests at the expense of the most vulnerable community members it purports to protect.

Holman tells Barn Raiser:

The original sheriffs in the United States were representatives of the crown in the United States and were supposed to be in charge of making sure that the appropriate resources went back to the crown. Sheriffs love to talk about the history of office … about the foundation of the office and how old it is, [going] back to Saxon England. But the reality is that when it was created, it was created as an office to ensure that the King was able to extract the resources necessary out of rural areas in England when he couldn’t send representatives himself to those areas.

It’s no accident, she says, that “the bad guy in Robin Hood is a sheriff.”

That changed with the American Revolution, but only so much. In the book, Farris and Holman write:

The autonomy and authority granted to sheriffs in the United States create an environment where sheriffs rarely change; elections do not create meaningful accountability; employees, budgets, and jails can be used for political gain; marginalized populations can be punished; right-wing extremism flourishes; and reforms fail.

In addition, Holman says, “Sheriffs don’t talk about the role that they played in maintaining and enforcing Jim Crow laws in the American South, or engaging in essentially genocide in the American West, particularly against indigenous people.” Nor do they talk about their roles finding and capturing enslaved people who had escaped from their enslavers, or as strikebreakers in the Gilded Age to the New Deal. Among other things, “Sheriffs often deputize the private security hired by owners, giving them the power to use the state to engage in violence against organizing workers,” Holman says. “Those are not topics of discussion among sheriffs on the history pages of their websites.”

It’s not ancient history. Today, sheriffs today routinely—though not uniformly—reinforce social hierarchies in how they enforce the law. They’re overwhelmingly white (91%), male (98%) and significantly more conservative than the populations they serve. And as Farris and Holman explore in detail, there are trickle-down consequences of sheriff’s attitudes in policing violence against women, traffic enforcement and immigration.

An imagined history

“The sheriff as an institution represents an imagined history,” Pishko writes. Mack’s promotion of the constitutional sheriff is built upon a foundation laid by white supremacist William Potter Gale, father of the Christian white supremacist “posse comitatus” movement in the 1960s, which gave birth to modern-day militias. In the early 1970s Gale declared: “The county sheriff is the only legal law enforcement officer in the United States of America!”

This is utter nonsense. In 1994, Mack sued the federal government over the constitutionality of the Brady Act, arguing that Congress couldn’t force local law enforcement to conduct background checks for gun sales. Three years later, Supreme Court ruled 5-4 in his favor but that ruling had nothing to do with Mack’s fantasy. Background checks were perfectly constitutional—regardless of what any sheriff might think. In the view of the Supreme Court, it was only the unusual act of Congress “commandeering” local assistance that was out of bounds, as it would have been for any local official. But Mack convinced himself otherwise, and who was the Supreme Court to tell him he was wrong? (Even though he used their ruling as a prop.)

Mack’s obsession with this case ended up costing him his job as sheriff: He was overwhelmingly defeated in the 1996 primary, his second race for re-election. It’s unusual for sheriffs to lose reelection. In fact, multiple surveys cited by Holman and Farris show they run unopposed 40-50% of the time. But Mack pulled it off. He spent so much time talking up the case in public forums and the media that voters felt he was neglecting his job. He ran for office several more times—for sheriff in Utah County, Utah; for the U.S. House (twice) and U.S. Senate; then for a sheriff post in Arizona—but with zero success.

Constitutional sheriffs get organized

The Tea Party backlash to Barack Obama’s 2008 election bought a change in fortune for Mack, setting the stage for the founding of CSPOA in 2012, which Cooper describes in detail.

In 2012, Mack’s Constitutional Sheriffs and Peace Officers Association (CSPOA), created with a collection of leading right-wing activists, gained significant traction within the Tea Party movement. Yet it remained relatively marginal among sheriffs until 2020, when it took off in reaction to Covid restrictions and the Black Lives Matter movement.

Pishko writes:

According to Mack and the CSPOA, sheriffs are not just law enforcement; they are special stewards of the U.S. Constitution—which is not just a regular legal document but a religious text to be interpreted literally—and can refuse to enforce federal, state, or local laws that they believe violate particular tenets of the “original Constitution,” which only includes the Bill of Rights (amendments one through ten). Per the CSPOA’s website: “The law enforcement powers held by the sheriff supersede those of any agent, officer, elected official or employee from any level of government.”

Mack was an early board member of the Oath Keepers, a far-right militia group founded by Stewart Rhodes in 2009. Eleven years later, Oath Keepers played a central role in the January 6 insurrection, with Rhodes sentenced to 18 years in prison before Trump’s mass pardon.

“[Rhodes] saw sheriffs in general, but particularly a player like Sheriff Mack, as the key upholders of his interpretation of the Constitution,” Cooper tells Barn Raiser. This means the “original Constitution” referenced by Pishko above, also known as the “organic Constitution,” where, Cooper says, “there were no legal or voting rights for indigenous people, there were no legal rights for women. There were no legal rights for black people.”

Another key player was Michael Peroutka, a lawyer who’s served on the board of the League of the South, which Cooper describes as “an old-school white separatist, Neo-Confederate organization.” Peroutka, says Cooper, “articulated the clearest vision of a real white separatist or white nationalist society.”

Also present for the Oath Keepers’ founding was Larry Pratt, founder of Gun Owners of America, a group to the right of the National Rifle Association. Pratt was also “a leader within the Christian Reconstructionist movement,” Cooper says, “and believed using various forms of militant struggles to bring about the conditions for a second coming.” According to Cooper, Pratt’s leadership with the Christian Identity movement helped spawn the 1990s wave of militia groups.

Christian identity, also espoused by Gale, is the belief that northern European people are the true descendants of ancient Israel, and thus God’s “chosen people.” The militias Pratt promoted drew inspiration from Gale’s idea that the sheriff, as supreme lawman, could enlist all military-age men into a posse he dubbed the “posse comitatus.” At first, the militia movement had far more success recruiting posses than sheriffs. A generation later, CSPOA formed to change that.

When Obama ran for re-election in 2012, says Cooper “these people were pretty down” and thought “we’ve lost in America.” Their strategy: build local pillars of power and test out local forms of theocratic rule.

Constitutional sheriffs gain new allies

Mack’s profile peaked between 2012 and 2015, as he played a lead role in opposing Obama’s gun reforms after the December 2012 Sandy Hook shooting. CSPOA was actively involved in armed standoffs in Nevada and Oregon involving the Bundy family. Yet, in the Republican party, Mack aligned more with Ron Paul than the alt-right movement that came to embrace Donald Trump. He was “old-timey,” as Pishko puts it, and not much into social media. “As the far right, alt right became really interested in memes and online culture, that is really not something that is familiar to a person like Richard Mack. It’s outside his frame of experience.”

Covid and the 2020 Black Lives Matter movement helped shift that frame, says Pishko. “The protests in 2020 created this concern among law enforcement that they needed to band together, and that the left broadly speaking—especially the criminal justice reform-oriented left—were enemies.” This perception bred a distrust that “was slower to hit city police departments,” but “really hit people on the ground, rank-and-file police, police unions, and sheriffs first. And sheriffs were the first to embrace it, because as elected officials they have more First Amendment rights to talk.”

Across the country, Pishko says, sheriffs began to argue they could not be reformed through legislation in the same way police departments were. “I honestly think the greatest success of the constitutional sheriff movement was creating this idea that … sheriffs are in some way immune to reform.”

Checks and balances are the core American democracy. They’re key to preventing a descent into demagogy on the one hand or unaccountable elite rule on the other. Sheriffs have largely escaped regulation and reform not because of principle, but because they wield enormous power.

“Sheriffs don’t talk about the role that they played in maintaining and enforcing Jim Crow laws in the American South, or engaging in essentially genocide in the American West, particularly against indigenous people.” – Mirya R. Holman, co-author of “The Power of the Badge: Sheriffs and Inequality in the United States.”

Holman and Farris illuminate this from multiple angles. Sheriffs run unopposed 40-50% of the time, and even when opposed they enjoy enormous advantages: incumbency (serving an average of 11 years versus four years for police chiefs), protection from national partisan politics and what Holman and Farris call the “scare off” effect. “Sheriffs are uniquely able to deter high-quality challengers at extremely high rates,” they write, “because the majority of sheriff candidates take a specific pathway to office—one that involves working in the sheriffs’ office that the candidate is looking to oversee.”

In addition to scaring off most challengers directly, sheriffs often chose their successors, retiring before the end of their term, so their appointed successor becomes the de-facto incumbent in their first election. This secures the chosen one’s loyalty and further discourages other contenders. There’s also a tight web of contractors, vendors and other business interest tied to the sheriff’s office who provide a significant resource deterrent to potential challengers.

Sheriffs also readily deflect outside oversight and accountability by attacking reform-minded politicians as anti-law enforcement or soft on crime. All these long-standing factors help insulate sheriffs from democratic accountability. The myth of the constitutional sheriff says all these flaws are what actually makes the office so good.

From 2012 onward, the nativist Federation for American Immigration Reform allied with Mack and CSPOA to promote the idea that every state was a border state and that sheriffs “could be local heroes in a national immigration crisis by enforcing the border in their own counties.” The tool for this was a federal program known as 287(g), established in 1996, that allows local agencies to act as immigration enforcement agents. Cooper focuses on North Carolina, where activists pushed back and helped elect Black sheriffs in major population centers who discontinued the practice.

CSPOA wasn’t happy with these sheriffs acting as the highest law in the land and worked with state Republican lawmakers to try to force the sheriffs to work with ICE or else be removed from office. This was virtually a mirror image of the 1990s case that first brought Mack to prominence, since it would require local sheriffs to enforce a federal law. Then Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper vetoed the effort, but it again underscored the racial politics that high-minded constitutional sheriff rhetoric constantly seeks to obscure.

Sheriffs after Trump’s return to office

In the year-plus since these three works came out, Trump’s re-election and the super-charging of ICE as an undisciplined national police force would appear to marginalize concerns about sheriffs, at least in the short run. But that’s not what’s happening on the ground.

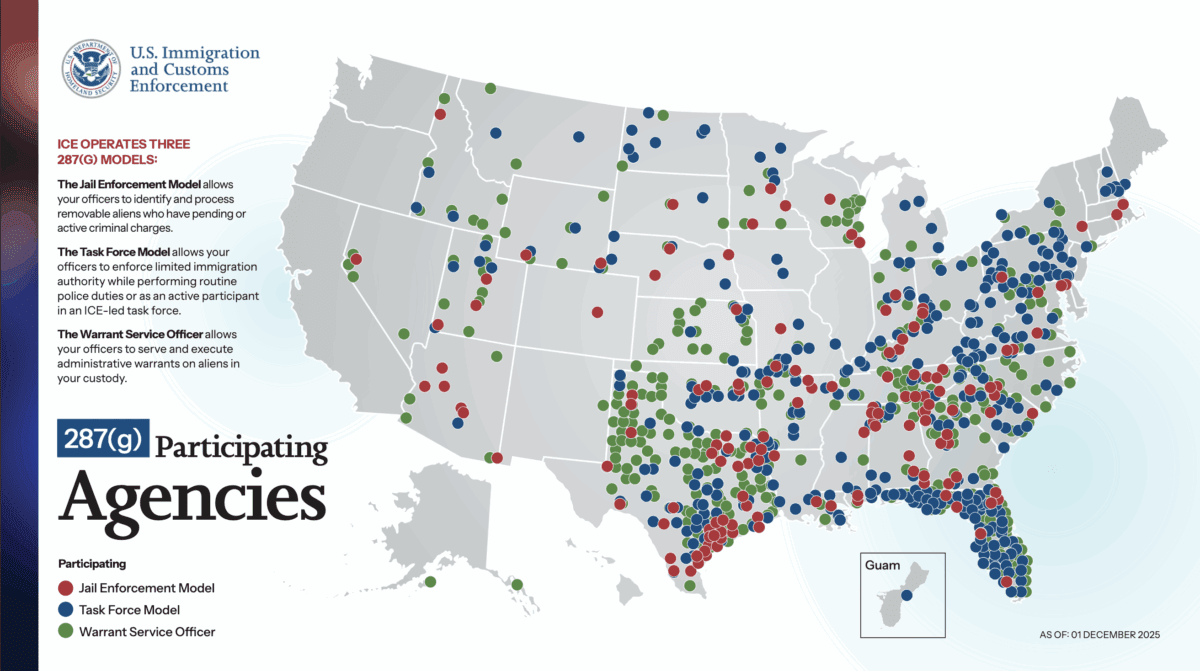

The National Sheriff’s Association, which has long disavowed the constitutional sheriff myth, is now headed by Chris West, a sheriff from Canadian County, Oklahoma, who was present at the January 6 insurrection. And sheriffs have been deeply involved with ICE via 287(g) agreements, which have expanded dramatically under Trump from 135 when he was sworn in to 1,098 as of October 21. Sheriff departments aren’t the only law enforcement agencies involved, but they are over-represented.

The agreements come in three different forms: First is the jail services model, where they’re trained to spot individuals in custody and hold them for ICE. Second is the warrant services model, which gives law enforcement the power to serve warrants for the civil immigration charges. Third is the task force model, in which individual officers are trained to act as ICE agents, which they can then do alongside their normal law enforcement duties.

Sheriffs have generally been amenable to working with ICE, but there’s less enthusiasm in some quarters than in the past on several counts, starting with less favorable financial incentives and concerns over losing staff to ICE. These are anything but trivial issues. In surveys of sheriffs conducted in 2012 and 2021, Holman points out, “If you ask what are the top three problems for your office, money or employee retention are always the top concerns.” While holding detainees in their jails has been a significant revenue source for some, building ICE’s own facilities could undercut that says Holman. “If the money continues to be centralized within ICE rather than paid out to sheriff’s offices, you may see a declining participation.”

In addition, she notes:

ICE is recruiting people to leave their positions in sheriff’s offices and go and work for ICE full-time. By all accounts it’s probably a better job in terms of pay and benefits, it’s better to work for the federal government than to work for local government. You have more employee protections. You have a broader capacity for advancements. Remember that sheriffs are the top of the heap and so if you’re interested in moving up and you’re in a sheriff’s office.

Finally, ICE’s brute force approach disrupts local economies. In Florida, for example, tourism and agricultural concerns have made some counties less enthusiastic about ICE raids than the administration assumed going in. While Trump’s focus on ICE raids in blue cities has drawn far more attention, with a clear-cut opposition between federal and local authority, the situation in rural communities is more nuanced, but is likely to become increasing strained over time.

“It seems like we’re seeing a more blatant adoption of MAGA ideology among sheriff’s departments,” Cooper says. But the concerns just cited could change things in the next few years, especially if rural economies sour. The constitutional sheriff myth can do just fine without the office, it seems. And perhaps the reverse may someday prove true as well.