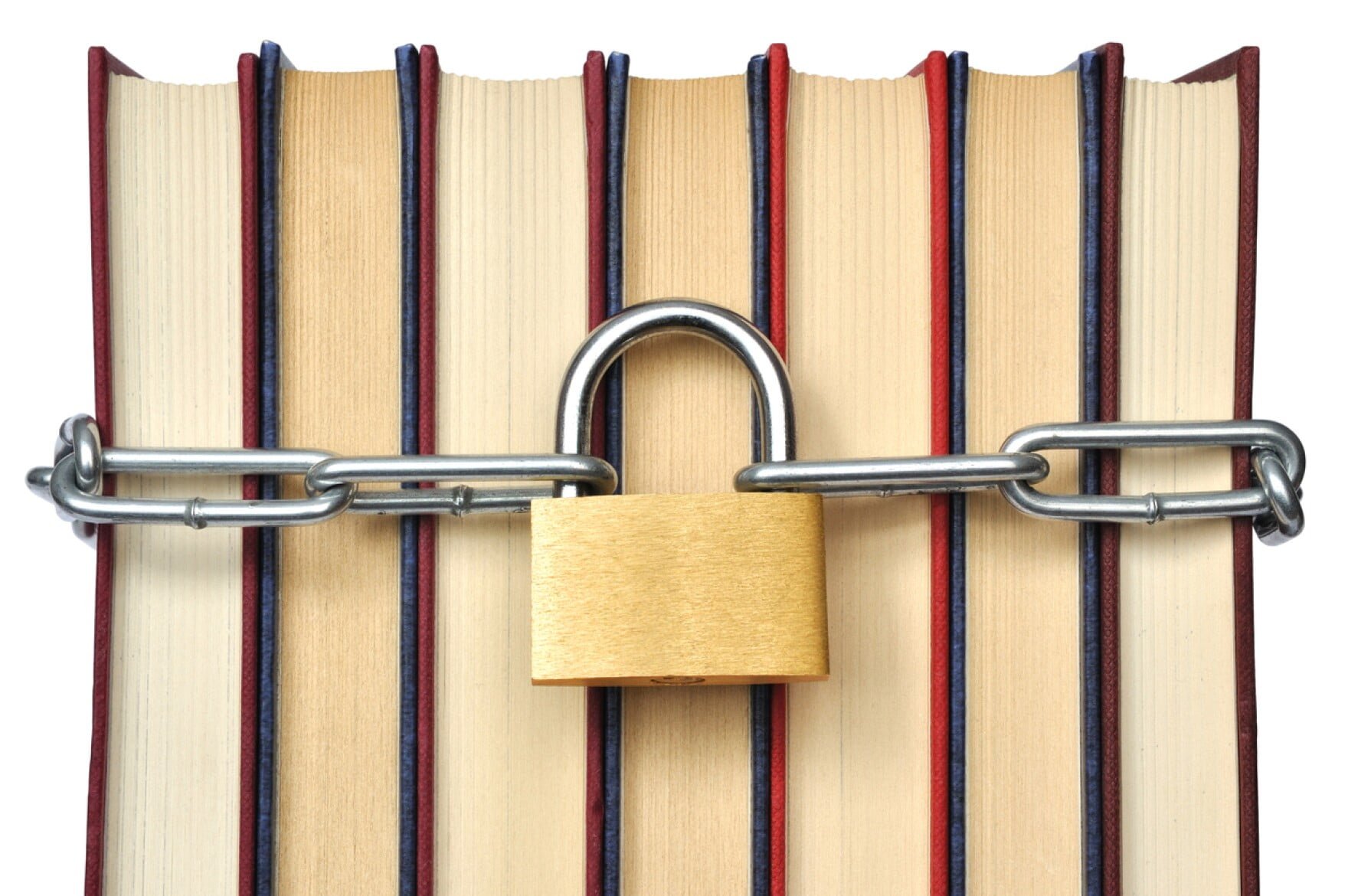

It’s 2022 and book bans are again prevalent throughout the United States. More specifically, Republican-controlled regions of the country, from entire states to school boards, are banning books by physically removing them from schools and libraries, prohibiting reference to ideas contained within those books, severely penalizing teachers and college professors who violate these censorship laws, and even trying to prohibit their sale and purchase outside of the classroom. Schools, libraries, and even booksellers are battlegrounds of our national culture wars, and those wars are about influencing the hearts and minds of future generations. Neglecting the lesson that neutralizing bad ideas comes through “discussion [of] the falsehoods and fallacies” and “the process of education” – “not enforced silence,”Republicans in power have started to ban viewpoints they disfavor. These bans plainly violate the First Amendment rights of teachers and students to access information, at least according to the current applicable legal precedent.

It is not a coincidence that Republicans began enacting these bans at the same time that the U.S. Supreme Court shifted dramatically rightward following the appointment of Justice Amy Coney Barrett in 2020. Six of the nine current Justices espouse radical conservative views and have already demonstrated their willingness to overturn decades of applicable precedent to reshape American society. The book bans have accelerated each year since 2020, with the American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom determining that in one three-month period alone, between September 1 and November 30, 2021, more than 330 unique cases were reported, doubling the number from 2020, and putting 2021 on record-breaking pace. PEN America identified 2,532 instances of individual book bans, affecting 1,648 unique book titles, from July 2021 to June 2022.

These 1,648 unique book bans were enacted by 138 school districts in 32 states, with Texas, Florida, Tennessee – where a Republican lawmaker suggested burning the banned books, and Pennsylvania having the notorious distinction of banning the third most books. In Pennsylvania, the Central York school district is responsible for 441 of the 459 bans. Locally, the Pennridge School District, the Central Bucks School District, the North Penn School District and the Downingtown Area School District have either removed books from library shelves or passed policies making it easier to do so.

Unsurprisingly, 40% of banned books included people of color, and 41% of them included LGBTQ themes or characters. The current crop of book bans stems directly from, and in repressive reaction to, an increase in public awareness of systemic, institutional forms of discrimination, particularly following the murder of George Floyd by police in May 2020. The bans include books that recognize the existence of systemic inequality, privilege, racism, and sexism.

The bans are also drafted using such vague language as to deprive educators of the ability to comply with the laws, under the threat of severe penalties, including financial penalties and even dismissal from their teaching careers. Teachers and librarians are placed in an impossible position of either censoring their speech and violating the core tenets of academic freedom, or facing discipline and even being embroiled in costly litigation. These vague, open-ended bans serve to chill a teacher’s ability to speak freely and instruct their students. Of course, the students are deprived of a well-rounded education, and of honest discussions of race and gender. By limiting the students’ access to information and literature, their ability to become mindful citizens is damaged.

In our current system of government, those of us who consider these book bans as a dangerous escalation of the culture wars, placing our society on the path toward totalitarianism, have two options: (1) vote out the legislators and school board members who pass book bans; and/or, (2) seek to have the book bans declared unconstitutional by the courts.

The book bans raise significant constitutional issues. In 1989, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that: “[i]f there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment, it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.” The Court has consistently ruled that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.” And, it recently reaffirmed the principle that “America’s public schools are the nurseries of democracy. Our representative democracy only works if we protect the ‘marketplace of ideas.’”

In its seminal opinion in Island Trees School District v. Pico, delivered in 1982 – forty years before the current book ban movement – the U.S. Supreme Court addressed whether the First Amendment limited school boards in exercising their discretion to remove library books. The opinion is instructive as the most directly applicable precedent to the question of the constitutional viability of the current book bans.

Anyone paying attention to the current book bans will find these facts familiar. The Island Trees school board obtained a list of books labeled by a conference of conservative parents as “improper fare”, and found 10 of the books in their school district’s library and one in the high school curriculum. The board ordered those books removed and justified the removal by describing the books as “anti-American, anti-Christian, anti-Semitic, and just plain filthy” characterizing the books as a “moral danger.”

The books banned by the board were: Slaughter House Five, by Kurt Vonnegut, Jr.; The Naked Ape, by Desmond Morris; Down These Mean Streets, by Piri Thomas; Best Short Stories of Negro Writers, edited by Langston Hughes; Go Ask Alice, of anonymous authorship; Laughing Boy, by Oliver LaFarge; Black Boy, by Richard Wright; A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But A Sandwich, by Alice Childress; Soul On Ice, by Eldridge Cleaver; and, A Reader for Writers, edited by Jerome Archer. The book removed from the high school curriculum was The Fixer, by Bernard Malamud.

After the board rejected the recommendations from a “Book Review Committee” to retain most of the books, a group of students sued, arguing that the school board’s actions violated their rights under the First Amendment.

On review, the Supreme Court initially addressed the question of whether the First Amendment imposed any limitations on a school board’s discretion to remove library books. Finding that the First Amendment extends to students, including their right to send and receive ideas in a school setting, the Court reasoned that: “the discretion of the States and local school boards in matters of education must be exercised in a manner that comports with the transcendent imperatives of the First Amendment.” Students’ free speech rights places limits upon the discretion of the school board. Therefore, the removal of books from a school library can violate the First Amendment rights of students.

The Court also found the students’ right to receive information and ideas to be a necessary corollary to the rights of free speech and the press guaranteed by the First Amendment. The Justices’ plurality opinion articulated the core principle that students should have access to the “marketplace of ideas” and the freedom to choose among those ideas. The Court reasoned that freedom to choose among competing ideas would prepare students to participate in the American political system.

The Court next addressed the scope of the First Amendment’s limitations over the discretion of school boards. Although the Court found that school boards retain substantial discretion, the First Amendment prohibits the suppression of ideas and thus bars school boards from exercising their discretion “in a narrowly partisan or political manner.” Notably, the example cited by the Court as being “narrowly partisan or political”, and therefore unconstitutional, is: “an all-white school board, motivated by racial animus, decid[ing] to remove all books authored by [B]lacks or advocating racial equality and integration.”

The Court held that “local school boards may not remove books from school library shelves simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books and seek by their removal to ‘prescribe what shall be orthodox in politics, nationalism, religion, or other matters of opinion.”

In the opinion authored by Justice William Brennan, the Court made it clear that book bans are subject to constitutional scrutiny. Bans that seek to suppress ideas or authors on partisan, political, or opinion-based reasoning are plainly unconstitutional. Yet that is precisely what is happening nationwide today. The latest iteration of book bans target disfavored viewpoints by attempting to silence them in a manner that plainly violates the First Amendment rights of teachers, librarians, and students. The constitutionality of the current crop of bans will again be tested by the courts and the issue will likely reach the Supreme Court of the United States. Rather than having the opinion shaped by the progressive stalwarts of the former Court like Justice Brennan and Justice Thurgood Marshall, who voted with the plurality in Pico, the decision will be drafted to suit the tastes of the current radical conservative super majority. It remains to be seen whether they will affirm the principle that the First Amendment does not tolerate the banning of books from libraries simply because people “dislike the ideas contained in those books” or whether they will help usher in a new era of American totalitarianism – where the banning and burning of books becomes the norm.