Written by Derek T. Muller, University of Notre Dame

Electors will gather across the United States in December 2024, just weeks after the election, and formally cast votes for president and vice president. They will send their votes to Congress, which will count them and determine who received the most votes. Typically, the casting of electoral votes is little more than a ceremonial process.

But the last time this process happened – in 2020 – it was anything but typical.

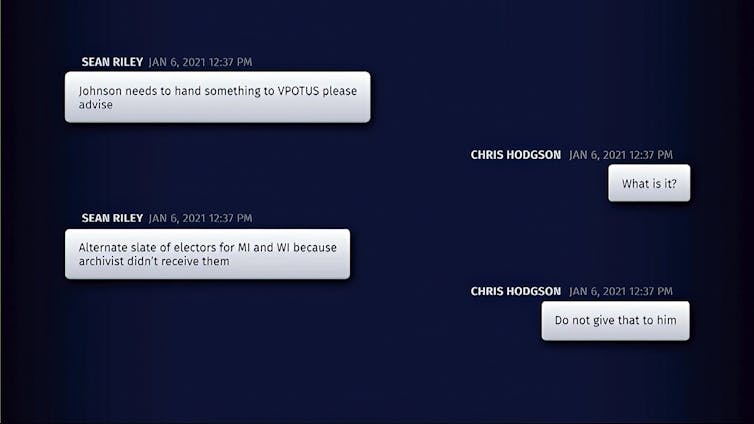

In seven states, in addition to the official electors, others calling themselves electors met and purported to cast votes for Republican Donald Trump on Dec. 14. They did this even though Democrat Joe Biden had carried their states in the November election. They sent their votes to Congress just like the official electors. When the electoral votes were counted on Jan. 6, 2021, some in Congress argued these purported alternative electoral votes meant the outcome of the election was still in doubt.

READ: Trump Loyalists Preview Strategies to Upend 2024 Election

Many of those purported electors now face criminal prosecution. Some may be convicted. And the odds of purported electors trying again in 2024 are less likely – but still possible.

‘Contingent’ or just fake?

These other electors labeled themselves “contingent” electors, arguing they could be the “true” electors if lawsuits Trump’s campaign filed to dispute the results ultimately went Trump’s way. Some of these other electors drew an analogy to Hawaii’s disputed presidential election in 1960. While Republicans carried Hawaii, a recount was underway when the electors met, and both Republican and Democratic electors sent their votes to Congress. The recount ultimately went Democrats’ way, and Congress counted the votes cast by Democrats.

In 2020, Republican electors in two states, New Mexico and Pennsylvania, sent certificates that expressly included contingency language. The certificates said their votes would be cast only in the event a legal proceeding declared those electors the true electors. This language appears to have saved them from prosecution.

READ: Why Trump’s ‘Fake Electors’ in Pennsylvania are Likely to Avoid Prosecution

Opponents and detractors have labeled them “fake” electors, because they lacked any state authority to act while presenting themselves as something genuine. These opponents note that Hawaii’s 1960 election had a real recount underway, and there was no serious litigation in any state in 2020 when the electors met. Almost all cases had been dismissed by Dec. 14, and a few pending appeals had no realistic chance of success. The sole purpose of these electors’ actions, opponents argue, was to sow distrust and confusion.

‘No authority’

Regardless of the adjective, these would-be electors had no authority. In Arizona, Georgia, Michigan and Nevada, most of those electors face criminal prosecution on charges such as forgery and fraud. The charges could result in sentences as high as 20 years’ imprisonment.

One major challenge in these prosecutions will be showing that the electors had the requisite intent to commit a crime.

On the one hand, it was quite obvious they were not the lawful electors at the time they purported to cast their votes, and they completed paperwork purporting to exercise lawful authority.

LISTEN: BBC News Reporter Mike Wendling on His New Book ‘Day of Reckoning: The Far Right’s War on Democracy’

On the other hand, if they can argue they were relying on the advice of Trump’s attorneys or other campaign officials, they might be able to show they lacked the intent to commit a crime. Michigan Attorney General Dana Nessel, for instance, claimed that these electors were “brainwashed.”

But each trial will have its own set of arguments and defenses, and it remains unclear what a jury might find in each case.

Removing ambiguities

Could there be a repeat of 2020 in 2024? The odds are lower but not impossible.

To start, Congress enacted the Electoral Count Reform Act of 2022. The new law now requires each state to certify its election results six days before the electors meet.

That means there cannot be pending litigation to sow confusion on the day the electors meet. It creates finality before the electors gather.

The new law also removes from the old law an ambiguous provision that allowed a state’s legislature to appoint electors after Election Day if the state failed to make a choice on Election Day. Some Trump supporters cited this provision to say that the legislature could name the Republican electors as the true winners sometime after Election Day.

But the provision was misunderstood – “failed to make a choice” did not mean that the legislature simply disagreed with the choice made by voters on Election Day. That provision has been removed, eliminating one more potential ambiguity in 2024.

The new law also changes the way Congress counts electoral votes. To start, it makes clear that the president of the Senate – typically, the vice president – has no unilateral authority to make any decisions when Congress counts votes. Additionally, the law makes it harder for members of Congress to object to counting votes.

LISTEN: The Growing Fascist Threat to American Democracy, with Jeff Sharlet

In previous years, one senator and one representative could object, which would force Congress to debate for up to two hours. It happened once in 2005 and twice in 2021.

Instead, the new law raises the threshold for objections to require support from 20% of the members in each chamber. That makes objections much less likely. Additionally, the new law expressly instructs Congress that final certification from the states “shall be treated as conclusive.”

Of course, electors could still try to stir up public discord in a state if their preferred candidate loses the election. Members of Congress can still try to object. No law can completely stop the risk of subversion after an election. These modest changes in law, however, will help reduce the likelihood that the aftermath of the 2024 presidential election looks like what happened after the election in 2020.

Derek T. Muller is Professor of Law at University of Notre Dame.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.